Medicare’s Hidden Fix for High Drug Costs

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Blog Post

What nurses can do and say depends on the state in which they practice. Variation in scope-of-practice laws, which regulate whether health professionals can prescribe, diagnose, develop care plans, and even administer eyedrops, have created a maze of policies and practice restrictions that are difficult to navigate—and not just for nurses, but for health systems and researchers as well.

We found that it’s virtually impossible today to compare laws across states or even understand them within a state. And while standardizing the language of scope of practice laws would solve the issue, that seems politically difficult. We describe a few ways to approach this problem, including a possible template, below.

In the course of collecting scope-of-practice laws for licensed practical nurses (LPNs), we looked for LPNs’ ability to perform routine tasks crucial to patient care, including dressing changes, tube maintenance, and vaccination administration. More often than not, we were unable to specify whether LPNs could perform these tasks or whether performing the tasks required more training. The lack of clarity extended to RNs as well. In fact, the most common categorization across the battery of scope-of-practice laws was “no information.”

This yawning gap in the regulatory landscape makes it almost impossible for research to inform policy—and for policy to inform research. It is particularly striking given the fact that there are over three million RNs and nearly 700,000 LPNs (sometimes called licensed vocational nurses), comprising the largest category of health professionals.

So who can fix this issue? Nurses’ scope of practice is dictated by each state’s board of nursing and is often buried in nurse practice laws, which vary widely. Efforts to synthesize nurses’ scope of practice laws across states include a study from Corrazini and colleagues and a policy brief and scorecard from the AARP Policy Institute. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) links directly to states’ nurse practice acts, when available. Despite these efforts, hundreds of scope-of-practice laws for nurses remain unclear.

Perhaps we could leverage an existing infrastructure, such as the Health Workforce Technical Assistance Center. This center is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration, whose primary goal is to provide “technical assistance to states and organizations that engage in health workforce planning.”

Another solution is to standardize the language-of-scope of practice laws to create consistency at the state level (North Carolina’s Board of Nursing offers one possible template.) Fortunately, a publicly available website where such laws could be posted already exists: the Scope of Practice Landscape, created by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

A timely solution is key. We’ve seen a trend toward expanding scope-of-practice in recent years, alongside increasing training requirements and educational attainment. Changes to these practice laws are often met with controversy and court cases, which should be informed by evidence. And while a better understanding of laws for RNs and LPNs—not to mention nursing aides, assistants, midwives, technicians, and clinical nurse specialists—would create short-term costs, it could accrue long-term benefits.

Studies show that more restrictive scope-of-practice laws for nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and certified nurse midwives often do not improve the quality of care, while the removal of these restrictions can increase access to and the capacity of care.

Relaxing these laws could even save money: one study of scope of practice for nurse practitioners found that relaxation could save Medicare over $40 billion annually. Because of the dearth of data, similar studies of the impact of restrictive or relaxed scope of practice laws for RNs and LPNs have yet to be conducted.

One exception is our recent study, which used the AARP report card and found that the ability to delegate tasks to unlicensed aides, which is also an element of nurses’ scope of practice, is correlated with turnover among LPNs.

Enhancing data quality and increasing the evidence base surrounding scope of practice laws for RNs, LPNs, and other health professionals will inform more than just state-level policy. As the shift from volume towards value continues, a key element is empowering patients to understand their rights and privileges across health care settings if they so choose.

The effort is worthwhile. Nurses are a bedrock of health care delivery, supporting preventative care, chronic disease management, and practice administration. More clarity surrounding what they can do and say, and how it affects patients, is a critical and overlooked part of enhancing value-based care.

The study, “The Relationship Between Scope of Practice Laws for Task Delegation and Nurse Turnover in Home Health,” was published in the Journal of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine on August 24, 2023. Authors are Molly Candon, Alon Bergman, Amber Rose, Hummy Song, Guy David, and Joanne Spetz.

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

A 2024 Study Showing How Even Small Copays Reduce PrEP Use Fueled Media, Legal, and Advocacy Efforts As Courts Weighed a Case Threatening No-Cost Preventive Care for Millions

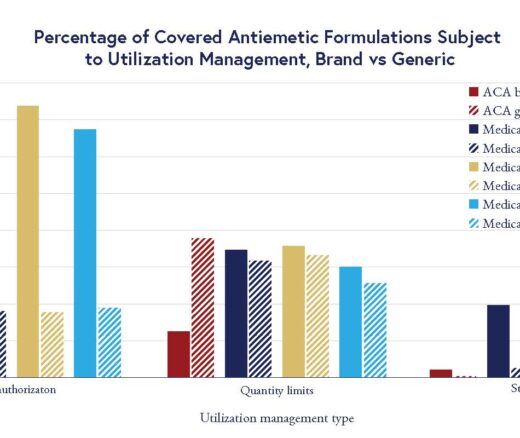

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use