How Playing Games May Save People’s Lives

The Growing Use of Gamification in Health Motivates People to Exercise More and Take Other Actions to Improve Their Physical Well-Being

Population Health

News | Video

Large hospitals and health systems have increasingly been moving beyond traditional clinical care to address the economic and broader social determinants of health (SDOH) that drive poor health and significantly affect the well-being of people in the low-income neighborhoods surrounding their facilities. This trend has accelerated in recent years, driven by policy changes, evolving community needs, and a growing recognition that factors such as housing, food security, transportation, employment, and economic stability have a profound impact on health outcomes.

This new model of health system and community partnerships was the subject of a May 2 virtual seminar at the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI). Titled Health Systems’ Role in Improving the Economic Well-Being of Communities, the seminar was co-hosted by LDI and the Penn Opportunity for Health Lab.

The event occurred against a backdrop of the latest White House executive orders and budget proposals calling for sweeping cutbacks in many of the federal programs that provide funding for low-income community development or the addressing of SDOH issues.

Moderated by LDI Senior Fellow Atheendar Venkataramani, MD, PhD, Director of the Penn Opportunity for Health Lab, the panel consisted of Sherry Glied, PhD, Dean of New York University’s Graduate School of Public Service; Ayesha Jaco, MAM, Executive Director of Chicago’s West Side United (WSU) initiative; Brookshield Laurent, DO, Founding Executive Director of Mississippi’s Delta Population Health Institute (DPHI); and David Zuckerman, MPP, President and Founder of the Health Care Anchor Network (HAN).

The discussion explored the expanding role of large health care systems as “anchor institutions” in their communities. Panelists examined a spectrum of involvement—from limiting their role to providing medical care, to using their purchasing and hiring power to support local economic development, to partnering with banks and U.S. Treasury-certified Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) that invest in low-income neighborhoods. They also discussed how some systems are addressing social determinants of health directly by supporting initiatives in areas such as food access, affordable housing, and transportation.

“The concept of anchor institutions actually emerged out of work that started at the University of Pennsylvania in the early 1990s,” said Zuckerman, who heads an organization representing more than 70 hospitals or health systems that have leveraged their hiring, purchasing, investing, and other key institutional assets in an effort to create stronger local economies that sustain healthy communities. “It was a response to the disconnect between what was going on campus and the health care disparities in the mostly low-income neighborhoods around campus. It was the start of the thinking about the role of institutions in bridging that divide and leveraging their assets to more intentionally reduce the disparities in place. At the heart of it was the idea of civic engagement, and by 2010, you started to see some publications looking at the different assets that health care organizations could leverage for this.”

“Today, HAN is working to catalyze our health systems to leverage their voice through policy advocacy in ways that think differently about their land and real estate in terms of how it connects to local amenities. For example, if you’re building a new Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), can you connect that with affordable housing? Can you connect that with a grocery store? So, it’s thinking more holistically about community needs beyond clinical care.”

In a rural version of an anchor institution, Laurent heads the Delta Population Health Institute, which is the engagement arm of the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYITCOM) at Arkansas State University (A-State). Its work focuses on low-income communities in eight Mississippi Delta states across the lower central U.S.

“Our parent institution is a private institution on Long Island, New York, and was invited to join with a rural public partner in Arkansas to start a medical school,” said Laurent. “The primary reason was to increase the physician workforce in the Mississippi Delta. The DPHI allowed NYITCOM in Arkansas to really lean into being an anchor institution promoting health and wellness across all sectors.”

She said A-State just published a report on the economic impact of the medical school, which has graduated 690 physicians since its opening in 2016. In fiscal 2023, the school was credited with bringing about $44 million into the region. Meanwhile, DPHI was heavily engaged in building local care capacity and collaborations in its various communities.

“When we are invited into these conversations, we immediately identify where the assets are, but our community partners often say it’s incredibly siloed because federal dollars don’t trickle down directly to community organizations, or those organizations may not have the capacity to acquire them because they don’t meet certain criteria,” said Laurent. “We step into this space as a convener to make people aware of what other assets are available and what the pathways are to share those resources.”

DPHI is currently working with CDFI Southern Bancorp, a local community financial institution, and a community health center to provide more community coordination and resources. Southern Bancorp is one of the country’s largest rural development banks and CDFIs and focuses on creating economic opportunity in underserved and under-resourced communities across Arkansas and Mississippi. DPHI has lately been invited into conversations related to addressing the large disparities around maternal and child health and food security in the region.

Meanwhile, 515 miles to the north in Chicago, Jaco’s West Side United initiative is collaborating with partners developing solutions to eliminate the life expectancy gap between residents of the wealthy Chicago Loop and those of the largely Black West Side communities that have the city’s highest poverty rates.

“WSU was born out of Rush University Medical Center’s Community Health Needs Assessment of 2016 and the thinking about how to serve the communities in the backyard of the Illinois Medical District,” said Jaco. “Rush wanted to think deeply and more broadly around health equity and set a table with six other health systems in the Medical District or that serve the West Side communities to come together around collective efficacy and collective impact.”

The combined systems’ workforce numbered about 43,000, the purchasing power was about $4 billion, and together they curated about 7,000 live births annually, Jaco said.

“So, the idea was to look inward to say, ‘What if we just directed one percent of our annual hires to West Side ZIP codes? Or what if we directed one percent of our spend to local businesses — who in some cases were in corridors that had not seen sizable investments since the riots of 1968?’” Jaco said. “Our planning committee has six system partners and 17 community partners who are now brainstorming around economic vitality and associated anchor strategies that can help us move the needle.”

“The idea was to think about neighborhoods and the built environment as related to social impact investing and food,” Jaco continued. “Looking at the drivers of the mortality gap, we saw it was cancer, cardiometabolic disease, opioid overdose, homicide, and infant mortality, so those were things we wanted to look at directly. Then we looked at our partnerships, like JPMorgan Chase, to think more deeply about our targets for supporting small businesses. Over the last seven years, we’ve had social impact investments of roughly $19 million that have gone out to community development financial institutions supporting projects in our ZIP codes.”

From the 30,000-foot economist’s view, Glied, a former Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the Department of Health and Human Services, as well as a former member of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, applauded these accomplishments but cautioned against generalizing the potential for all health systems to do the same.

“Clearly, there are health care organizations that have been really successful in doing their core duty and also bolstering their communities,” said Glied. “But I want to imagine a health care system or a hospital that up to now has not done that and ask the question, ‘should this be the priority for their leadership?’ I think the answer is maybe. I’m an economist, so I’m always focusing on tradeoffs. And the reality is no institution, no organization can do everything. So, the question is where should its priority be? And for hospitals, I would say absolutely, without question, health care delivery has got to be the lodestar. In management speak, it must be the core competency of health care systems. And the reason for that is that it is a function that only health care systems and only hospitals can serve.”

“It is really important to recognize that providing high-quality health care is a benefit in itself,” Glied continued. “There is growing evidence that people who get better quality medical care can do better in other aspects of their life, and that having your health conditions managed well allows you to take on jobs and do other things. So, I don’t think we should scant the importance of that core function of the health care system.”

“There doesn’t have to be a tradeoff between being an anchor institution and providing high-quality health care,” said Glied. “But there can be. We must be cognizant of the time, energy, and attention of the leadership. In a safety-net health care system or hospital that is always struggling and is not providing high-quality care, it is not clear to me that deflecting management attention to being an anchor institution is the right way to go. So, I think we just want to be really cautious and thoughtful about making sure that health care systems and hospitals first do the thing that we all depend on them to do and that no one else can do. And then as a secondary function, think about what they can be doing on top of that.”

As the session came to a close, Venkataramani asked each of the panelists for a brief statement about how they see the role of anchor institutions developing and changing over the next several years. These were their answers:

Zuckerman: “It’s going to be a tough period in the coming few years with resources being slashed at all levels, and this is when we need our institutions to step up and not pull back, and to think creatively about how they can leverage resources. It’s in their self-interest to think about the long-term well being of the communities they serve.”

Laurent: “We’re anticipating the challenge and that if we don’t step in, it can get worse. Something I’ve learned is that in periods of intense pressure and pain, people really do step up. They innovate. They get stuff done. This is not a time to step back because it’s actually a matter of life or death. We just don’t have an option.”

Jaco: “We have seen the strength of coming together during the pandemic; some of our system partners name racism as the first pandemic, and that work never stops. For us, it’s thinking about the nuanced needs that our communities are going to have in a way that they did not have coming out of the pandemic. Our goal is to be proactive and not reactive as we evolve and renew ourselves to be ready for what’s to come.”

Glied: “I just agree that we all have to work together, or we will fall apart. We will have to hold it together.”

The Growing Use of Gamification in Health Motivates People to Exercise More and Take Other Actions to Improve Their Physical Well-Being

Pa.’s New Bipartisan Tax Credit is Designed to be Simple and Refundable – Reflecting Core Points From Penn LDI Researchers Who Briefed State Leaders

Focusing in on Some of Health Care Policy’s Most Urgent Issues

Highlighting 10 Ways LDI Fellows Put Their Research Into Action

From AI-Powered Public Health Messaging to Stark Divides in Child Wellness and Medicaid Access, LDI Experts Highlight Urgent Problems and Compelling Solutions

An LDI Expert Offers Three Recommendations That Address Core Criticisms of the ACA’s Model

Administrative Hurdles, Not Just Income Rules, Shape Who Gets Food Assistance, LDI Fellows Show—Underscoring Policy’s Power to Affect Food Insecurity

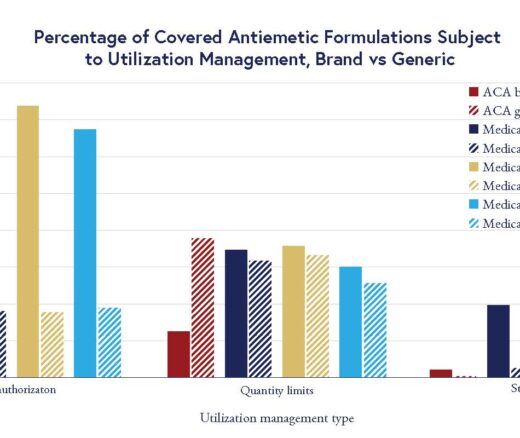

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea