Health Care Access & Coverage

Blog Post

Beyond Physicians: Interdisciplinary Teams in Integrated Care

On the frontier of behavioral health (part 2 of 2)

In our recent blog post, we explore barriers to behavioral health care in the United States and discuss an alternate strategy: integrated care. Traditionally, integrated care has entailed behavioral health care delivered by a primary care provider. Decades of research and dozens of randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that integrated care, particularly the collaborative care model, can improve a host of outcomes. Increasingly, however, health systems and practices are testing new approaches to integrated care that optimize the use of personnel by incorporating interdisciplinary teams of advanced practitioners and other community stakeholders. A number of initiatives at Penn Medicine showcase this approach:

1. Triaging integrated care for veterans

Since 2007, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has invested in a nationwide program embedding behavioral health specialists and care managers into primary care clinics. A recent Health Affairs study analyzed data from 5.4 million VA primary care patients at 396 clinics in 2013-16. The authors found that veterans who received treatment in clinics with higher engagement in integrated care had more primary care and behavioral health visits than those seen at clinics with lower engagement in integrated care. On average, patients who received more integrated care visits utilized less specialty care.

Philadelphia’s Behavioral Health Lab (BHL) has led the way in delivering integrated care at VA clinics. Since its inception in 2003, BHL has contributed to a body of evidence on the effectiveness of integrated care for veterans suffering from depression and alcohol use disorder. An ongoing trial led by Penn Psychiatry professor David Oslin, MD builds on this foundation by incorporating triage. Using validated screening tools to assess patients’ behavioral health, staff identify those who are likely to benefit from treatment by a primary care provider versus those patients requiring more intensive care, who are referred to a specialist. Staff then streamline the engagement process by helping to schedule (and reschedule) appointments.

By redirecting patients with lower levels of acuity away from specialty care, integrated care means treatment for common behavioral health conditions can occur within the comfort of a primary care practice, which translates into lower co-pays than specialists. As a result, psychiatric specialists can focus their limited time on patients facing particularly severe, treatment-resistant conditions.

2. Proactive screening in the hospital

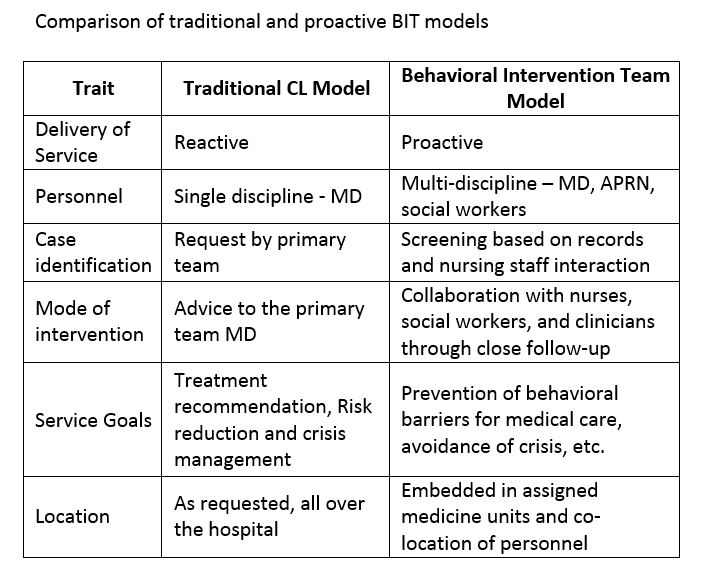

Health systems are beginning to recognize the opportunity to identify and treat patients with behavioral health care conditions upon admission for non-psychiatric illnesses. One approach is to replace the traditional psychiatric consult-upon-request with proactive psychiatric screening and triage of patients soon after admission. This form of integrated care often involves screening by a psychiatric nurse practitioner and/or licensed clinical social worker, and can result in consults with psychiatrists for patients with serious mental health needs.

Source: Health Affairs

A study of an integrated care initiative at Yale-New Haven suggested that this proactive, team-based approach is associated with a decreased length of stay among patients on medical units; a cost analysis found that, from the hospital perspective, they produced lower per-case costs and, because of shorter lengths of stay, incremental revenue from new admissions into the units.

A more rigorous study at Johns Hopkins Hospital found that patients seen by a behavioral health intervention team in general medical units utilizing a proactive approach had a shorter time to consult, and a shorter length of stay than patients seen by the reactive consult service. The shorter time to referral to psychiatric consultation is an important feature of the proactive approach: one Canadian study found that that patients with a longer time to referral had longer lengths of stay, even after adjusting for their medical severity.

Penn Medicine is also experimenting with integrated care in acute care settings. On two floors at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, every patient is proactively screened by a psychiatric nurse practitioner and licensed clinical social worker on their first day of admission. Early reports from this trial, led by Penn Psychiatry assistant professor Cecilia Livesey, MD, demonstrate an untapped need. Before the trial, only 6% of patients received any sort of behavioral health intervention; afterwards, nearly half did. In addition to a shorter length of stay, this program has also been associated with a reduction in the use of restraints, an important outcome among hospitalized patients with serious mental illness.

Dr. Livesey’s study, the Mental health Evaluation, Navigation, and Delivery (MEND) trial, showcases the adaptability of integrated care models beyond primary care. Like Dr. Oslin’s primary care model at the VA, MEND uses team-based triage that allocates personnel and patients more efficiently. Although half of all patients in MEND required some behavioral health intervention, four out of five were treated by a psychiatric nurse practitioner and/or licensed clinical social worker, giving the resident psychiatrist time to focus on higher-acuity patients. MEND demonstrates the power of interdisciplinary teams and proves that many patients can be effectively treated without a physician.

3. Peer support after an overdose

Providers are not the only ones playing an important role in delivering integrated care, particularly when addressing substance use disorder. Drawing on evidence from peer support models for severe mental illness, a number of states, cities and health systems have engaged trained peers in emergency departments (ED) as part of opioid overdose response plans. Recent studies focus on scoping, implementation and replication of programs. However, evidence of outcomes has been limited for these relatively new – and widely varying – programs.

At Penn Medicine, the Center for Opioid Recovery and Engagement (CORE) is reporting promising preliminary outcomes for a peer support overdose intervention. CORE identifies patients in the ED who have been treated for an overdose, and initiates treatment geared towards recovery while they are in the hospital. Patients are partnered with a peer who has personal experience with opioid recovery and been certified as a recovery specialist. Peers are a critical part of treatment, working with patients to develop individualized recovery plans and to provide ongoing support after discharge.

Source: Penn Medicine News

Speaking of her own experience overdosing on opioids, Nicole O’Donnell, now a certified recovery specialist at Penn Medicine, says “Absolutely nothing like this existed for me… I was taken to the hospital, and people were so mean. They didn’t care if I had a ride home, they were just done with me. I wasn’t so far gone at any point that an offer to help wouldn’t have resonated with me, but they gave me no resources. Nothing.” Now, Nicole provides the support she lacked during her own recovery to other patients, helping decrease the odds that they slip through the cracks after leaving the ED. “Sometimes I see that patients just don’t want to talk to someone who hasn’t gone through what they’re going through,” she says.

Early results from CORE have been striking: within 30 days, 68% of patients who receive the CORE intervention are engaged in treatment compared to <5% at baseline. And fewer patients are returning to the ED: About 1 in 5 patients consulted by a CORE certified recovery specialist ended up back in the emergency room within 30 days, compared to about 1 in 3 at baseline.

Incorporating peer support, community health workers and other relevant stakeholders into integrated care represents an opportunity to increase access to and the quality of behavioral health treatment – thereby improving patient outcomes – all while containing costs.

Early results from integrated care trials at Penn Medicine and other health systems have found that interdisciplinary teams can increase efficiency and remove barriers to behavioral health care. While research is ongoing, one thing is certain: the current behavioral health landscape, characterized by red tape, scarcity of in-network providers, and high out-of-pocket costs, places a heavy burden on patients who are already struggling. Integrated care is a promising model for lightening the load.