AI Device Firms Pay $60M to U.S. Doctors, Raising Oversight Concerns

In a First-of-Its-Kind Analysis, Researchers Track Industry Payments Tied to AI Medical Devices and Call for Stronger FDA Oversight, Transparency, and Aid for Underserved Hospitals

Blog Post

Produced in conjunction with the Population Aging Research Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

Thirty years after the Americans with Disabilities Act, conversations about mass incarceration in the United States rarely include mention of disability. People with disabilities are more likely to end up in prison and prisons can make disabilities worse. How can we break this link and reverse this social and economic exclusion of disabled people?

In a recent study I conducted with LDI Associate Fellow Stacey Bevan and Senior Fellow Courtney Boen, we examined the 2016 Survey of Prison Inmates administered by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. We found that disabled people are vastly overrepresented in prisons and were more likely than nondisabled people to have previously resided in punitive and therapeutic institutions.

While roughly one quarter of the general population in the United States are disabled, disabled people make up around two-thirds of the 2016 state and federal prison population, with 40% reporting a psychiatric disability and 56% reporting a nonpsychiatric disability. Our study found striking disparities by race-ethnicity and gender, with Black, Hispanic, and multiracial disabled men especially overrepresented in prisons. While men make up the vast majority of the state and federal prison population, disability prevalence is much higher among incarcerated women.

We found that disabled incarcerated people are more than twice as likely as nondisabled incarcerated people to have previously resided in therapeutic institutions, such as psychiatric hospitals, residential treatment facilities, and group homes (46% vs. 20%). While these institutions may be intended to provide care and be more humane than punitive institutions, they can still reinforce social exclusion and oppression. The finding points to a critical need to understand why institutions that confine disabled people are creating such a strong pathway to prison.

Opportunities to intervene occur at three critical times:

Policy and political actions aimed at decarceration and reducing social and legal exclusion of disabled people are needed. Our findings suggest that interventions are needed to improve punitive and therapeutic institutions and reduce inequities at the intersections of disability, race-ethnicity, and gender. Scholars, policymakers, and advocates must prioritize the well-being of disabled people and work to redress inequities sustained by the prison system and other carceral institutions.

The article, “The Links Between Disability, Incarceration, And Social Exclusion” was published in October 2022 by Laurin Bixby, Stacey Bevan, and Courtney Boen in Health Affairs.

In a First-of-Its-Kind Analysis, Researchers Track Industry Payments Tied to AI Medical Devices and Call for Stronger FDA Oversight, Transparency, and Aid for Underserved Hospitals

Health Insurer Acquisition of PBMs — the Prescription Drug Middlemen — Raised Premiums for Some Part D Beneficiaries

LDI Senior Fellow Honored for International Research Achievements

First Rural Health Grants May Not Go to Areas With the Greatest Needs, LDI Experts Find

Research Brief: Cash Transfer Programs Improve Birth, Nutrition, and Early Childhood Health Outcomes

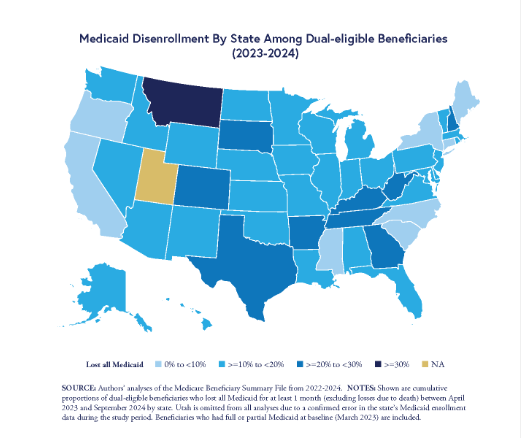

Chart of the Day: Researchers Urge Easier Renewals and Better Support To Prevent Gaps in Care