How Playing Games May Save People’s Lives

The Growing Use of Gamification in Health Motivates People to Exercise More and Take Other Actions to Improve Their Physical Well-Being

Blog Post

The global response to HIV includes direct funding for research, prevention, and treatment, including nearly $100 billion to date from the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). This type of aid helped slow the spread of HIV. However, a July 2022 report from the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) delivered bad news: Progress is faltering, largely because of the economic impacts of COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine. The number of people with new HIV diagnoses last year was three times the UNAIDS’ goal.

Amid calls to renew commitments to HIV prevention efforts, new research from LDI Associate Fellow Aaron Richterman and Senior Fellow Harsha Thirumurthy highlights an approach to achieving a range of HIV public health goals: Just give people cash.

Cash transfers are direct payments to eligible people. Unlike behavioral incentives, such as one-time payments for visiting a clinic, cash transfers are usually sustained, with few or no conditions. The programs are increasingly common and include, for example, the U.S. Child Tax Credit. Cash transfers are intended to alleviate poverty by stabilizing household finances. But evidence suggests they have health impacts, too.

Richterman and Thirumurthy evaluated the effects of cash transfer programs in low- and middle-income countries with generalized HIV epidemics. They used 1996-2019 data from national surveys and surveillance studies for 42 countries, 21 with cash transfer programs and 21 without. Most were in Africa (86%) with the rest in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia. Programs varied in the amount of money provided and included unconditional programs and programs that required, for example, that recipients’ children attend school.

The results linked cash transfer programs to immediate reductions in new HIV diagnoses—6% within the first year, compared to countries without cash transfers. By the second year, cash transfers were also linked to increased receipt of antiretroviral therapy, which grew over time. AIDS-related deaths were reduced by up to 25% by year nine. The analyses controlled for funding from PEPFAR and the Global Fund that directly target HIV outcomes.

Overall, women in countries that introduced a cash transfer program had a 33% lower risk of sexually transmitted infections (a proxy for HIV exposure). Recent HIV testing increased 160% for women and 220% for men. The authors explain that cash transfers might have particularly positive impacts on the finances of women and girls, leading to less transactional sex and reduced HIV exposure and transmission, a hypothesis supported by their other work. Cash transfers may help people access health care including HIV testing, diagnosis, treatment, and treatment adherence. With antiretroviral therapies now allowing people to achieve undetectable, untransmittable viral levels, these mechanisms improve individual health and decrease HIV transmission in the population.

Richterman and Thirumurthy note that the cash transfers are not anti-HIV programs or even public health initiatives: They are social protection programs that could play a key role in ending the HIV pandemic.

The results apply to U.S. policies. Richterman previously showed that relaxing income eligibility limits for the U.S. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) was associated with fewer annual HIV diagnoses. Rather than being considered as strictly antipoverty programs, Richterman and Thirumurthy say that cash transfers should also be recognized as anti-HIV measures. In addition, cost-benefit analyses of social protection programs should include the potential for HIV control.

The study, “The Effects of Cash Transfer Programmes on HIV-Related Outcomes in 42 Countries from 1996 to 2019,” was published on 18 July 2022 in Nature Human Behavior. Authors include Aaron Richterman and Harsha Thirumurthy.

The Growing Use of Gamification in Health Motivates People to Exercise More and Take Other Actions to Improve Their Physical Well-Being

Pa.’s New Bipartisan Tax Credit is Designed to be Simple and Refundable – Reflecting Core Points From Penn LDI Researchers Who Briefed State Leaders

Focusing in on Some of Health Care Policy’s Most Urgent Issues

Highlighting 10 Ways LDI Fellows Put Their Research Into Action

From AI-Powered Public Health Messaging to Stark Divides in Child Wellness and Medicaid Access, LDI Experts Highlight Urgent Problems and Compelling Solutions

An LDI Expert Offers Three Recommendations That Address Core Criticisms of the ACA’s Model

Administrative Hurdles, Not Just Income Rules, Shape Who Gets Food Assistance, LDI Fellows Show—Underscoring Policy’s Power to Affect Food Insecurity

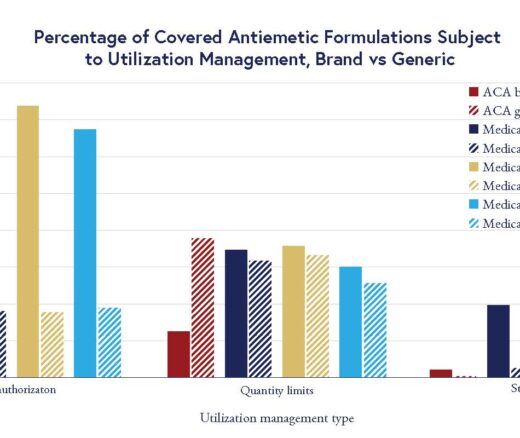

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea