Medicare’s Hidden Fix for High Drug Costs

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Blog Post

The news surrounding Medicare’s coverage decision on Aduhelm brought new attention to Medicare coverage policy, a topic we examine in a new Health Affairs paper. I am fascinated by coverage policies as a tool for addressing overuse of health care services. In contrast to broad, blunt incentives to reduce spending like cost sharing or global budgets, coverage policies can, in theory, create nuanced incentives based on medical evidence.

Medical care only qualifies for coverage by Medicare if it meets the legal standard of being “reasonable and necessary.” In our study, we analyzed health insurance claims that were denied for failing to meet this standard of medical necessity.

We set out to answer a few questions: Do insurers often deny claims on the grounds that the services are not medically necessary? Do private Medicare Advantage insurers have more or different medical necessity criteria than government Medicare? What types of services are denied according to each set of rules?

Little is publicly known about coverage denials due to medical necessity rules. Denials aren’t tracked in most datasets used in research. But by partnering with Aetna, we were able to study these denials in Aetna Medicare Advantage (MA).

Medical necessity rules in MA come from two sources. MA plans follow coverage rules made by Medicare for what is reasonable and necessary. These coverage rules are codified in Medicare’s National Coverage Determinations, Local Coverage Determinations, or its policy manuals. But Medicare does not make formal coverage determinations for many services. In these cases, MA plans can make their own rules.

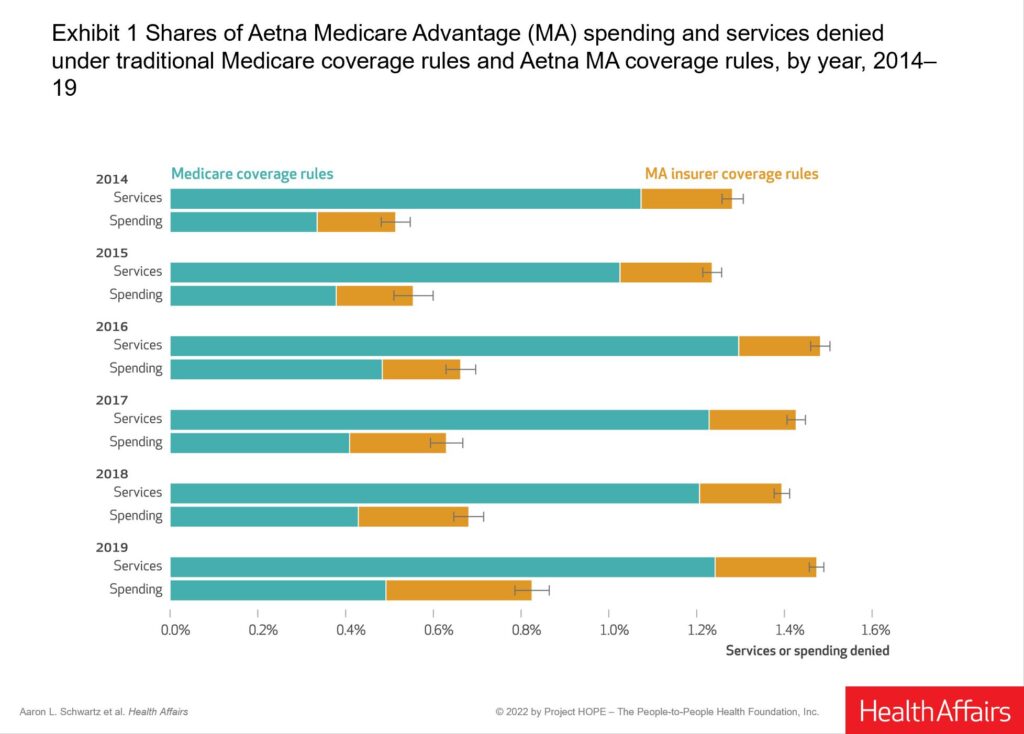

Denial rates were modest but nontrivial. Almost 1% of spending was denied on medical necessity grounds in 2019, amounting to about $60 per beneficiary. Most denials were based on government coverage rules rather than MA insurer rules. But MA rules accounted for about one-third of denied spending, a significant portion.

I was most surprised by the types of services facing denials. The vast majority of Medicare’s rules targeted lab tests. The most frequent denied service was glycosylated hemoglobin (A1c) testing, not exactly a service typically thought to be low-value.

Private insurer rules tended to target high-priced injectable drugs like those used in oncology. This is consistent with our prior finding that much of this spending is targeted by prior authorization tools, which also employ medical necessity rules.

Ultimately, the big policy question is how valuable these coverage restrictions are and the relative contribution of government and private insurers to this value. We can’t answer those questions yet. Our estimates of denied spending are only one element of the savings that might be achieved by coverage restrictions; denied spending amounts don’t include avoided spending because of deterrence effects of coverage policies. Also, these results also do not account for substitutes or complements of restricted services, whose use can be affected by the coverage rules. By showing how coverage rules have been employed by government and private insurers, I hope this work informs researchers and policymakers eager to understand the function of managed care in our health insurance markets.

The study, Coverage Denials: Government and Private Insurer Policies For Medical Necessity In Medicare, was published in the January 2022 issue of Health Affairs. Authors include Aaron L. Schwartz, Yujun Chen, Chris L. Jagmin, Dorothea J. Verbrugge, Troyen A. Brennan, Peter W. Groeneveld, and Joseph P. Newhouse.

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

Pandemic-Era Medicare Flexibilities Have Proven Effective, Popular, and Safe

A 2024 Study Showing How Even Small Copays Reduce PrEP Use Fueled Media, Legal, and Advocacy Efforts As Courts Weighed a Case Threatening No-Cost Preventive Care for Millions

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior