Experts Warn Addiction Policy is Weak Despite Falling Overdose Deaths

Penn LDI Panel Urges Family-Focused Strategy and Stronger Health System Response

News | Video

A collaborative project of a University of Pennsylvania research team and Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services (DBHIDS) has developed a new type of data infrastructure for regional suicide prevention efforts.

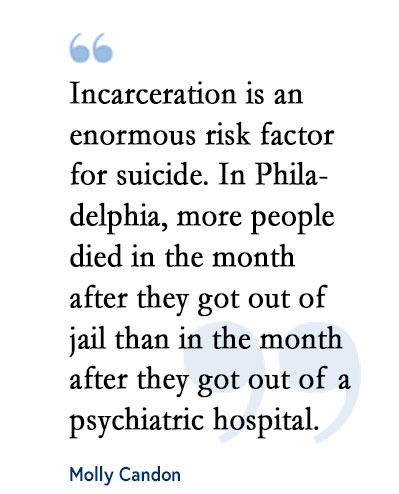

Current suicide risk screening systems tend to rely on clinical factors, such as psychiatric hospitalization records. They rarely include risk data from nonclinical settings such as jails or emergency shelters. Co-led by LDI Senior Fellow Molly Candon, PhD, and DBHIDS Director of Research Suet Lim, PhD, the project built a community-level data infrastructure that encompasses administrative records including suicide death records, Medicaid-funded behavioral health claims, incarceration episodes, emergency housing episodes, and involuntary commitment petitions. Candon is an Assistant Professor at both the Perelman School of Medicine and the Wharton School.

The research was done against the backdrop of the rising number of suicides among Philadelphia Medicaid recipients and higher rates of suicide among Black youth.

The study included more than 1,000 suicides of Philadelphians between 2003 and 2018. The focus on Medicaid was because of that population’s heightened vulnerability to suicide and disproportionate exposure to known suicide risk factors like poverty and unemployment.

“Current predictive algorithms for suicide risk aren’t typically effective because they tend to follow people who are coming out of a psychiatric hospital or are actively engaged in antidepressant therapy—and we know that most people who die of suicide aren’t showing up in those spaces,” said Candon.

“The goal of this study was to get a better understanding of where people actually were in the time leading up to their suicide because that data identifies where potential interventions might be targeted,” said Candon.

“Administrative data are commonly siloed and it’s very difficult to merge the different sets. That was the key to this work,” Candon continued. “The DBHIDS-led behavioral health system enabled us to combine Medicaid claims, jail admissions, emergency shelter stays, and other disparate sources and the result was very powerful. For instance, we found that incarceration is an enormous risk factor for suicide. In Philadelphia Medicaid, more people died in the month after they got out of jail than in the month after they got out of a psychiatric hospital. So, this new data infrastructure expands our ability to intervene in really meaningful ways and think outside the box, which I think is needed when it comes to preventing suicide.”

“We also know that Medicaid can be a protective factor for suicide,” said Candon. “If you are insured, you can access mental health and substance use services that you can’t access when you’re not insured.”

“A really unique aspect of this work was our ability to translate our findings into meaningful practices and policies as we collaborated with DBHIDS,” said Candon. “Once we crunched the numbers, we were able to quickly present the findings to relevant stakeholders. We’re currently in the process of building a curriculum that that could be rolled out in nonclinical settings that emphasizes mental health literacy and suicide prevention efforts.”

“One thing we’re very excited about is the possibility of leveraging peer specialists to lead these efforts,” said Candon. “These are people with shared, lived experience. They’ve gone through it, and they’ve come back, and they can walk someone through to the other side in a much more effective way than someone like I could. So, our goal is over the next year to develop this curriculum and to test it out with different people to see what works and what doesn’t and what else we should know.”

“In order to meaningfully prevent suicide deaths, we need to cast a much wider net over the risk factors that may be contributing to the problem,” said Candon. “We know other cities, counties, and states are thinking about how to use their data in ways that result in more accurate risk predictions. And in order to achieve that, we all need to be feeding better and more relevant data into those risk algorithms so that we can do a better job of identifying the places to intervene.”

Penn LDI Panel Urges Family-Focused Strategy and Stronger Health System Response

Remote Nurses Improved Quality Slightly but Can’t Replace Nurses at the Bedside, a New Study Finds

Washington State’s First-in-the-Nation Insurance Plan Begins Payouts in Mid-2026, and Researchers Will Weigh its Effect on Care, Costs, and the Long-Term Care Markets

Without Pressure From Congress, NHANES — Which Helped Uncover High Levels of Childhood Lead, Nutritional Deficiencies, and Forever Chemicals — Will Cease to Exist

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

Former CMMI Leader Liz Fowler Cites Rigid Federal Scoring Rules and Bureaucratic Impatience for Pilot Failures