Integrated Care Plans Didn’t Boost Medicaid Enrollment for the Poorest Seniors

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Brief

Safety net hospital funding from federal, state, and local governments relies on definitions that yield highly variable results. This variability can prevent funders from efficiently targeting financial resources to the intended hospitals. For example, in a new LDI study, different safety net hospital definitions captured as low as 2% or up to 69% of rural hospitals. Definitions varied in stability: Some produced the same hospitals year-to-year while others had less than 20% overlap. By understanding the tradeoffs of different definitions, funders can transparently choose definitions that ensure safety net hospitals fulfill their mission—providing necessary care, regardless of patient income or insurance status.

Financial support for safety net hospitals is assigned using multiple definitions: Some, such as the Medicare or Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) definitions, measure care to certain beneficiaries. Others combine measures into indexes to capture populations with high social disadvantage. Multiple definitions help policymakers capture diverse safety net aspects but can lead to redundancy and resource mistargeting. For example, using the Medicaid DSH definition to support hospitals serving Medicaid-covered or uninsured patients resulted in up to 30% of payments going to facilities that did not provide substantial services to these patients, LDI Senior Fellow Paula Chatterjee showed. New work by Chatterjee, LDI Senior Fellow Amol Navathe, former Senior Fellow Josh Liao, and colleagues seeks to help government funders choose safety net hospital definitions that match their goals by showing which hospitals are selected by different definitions and the stability of selections over time.

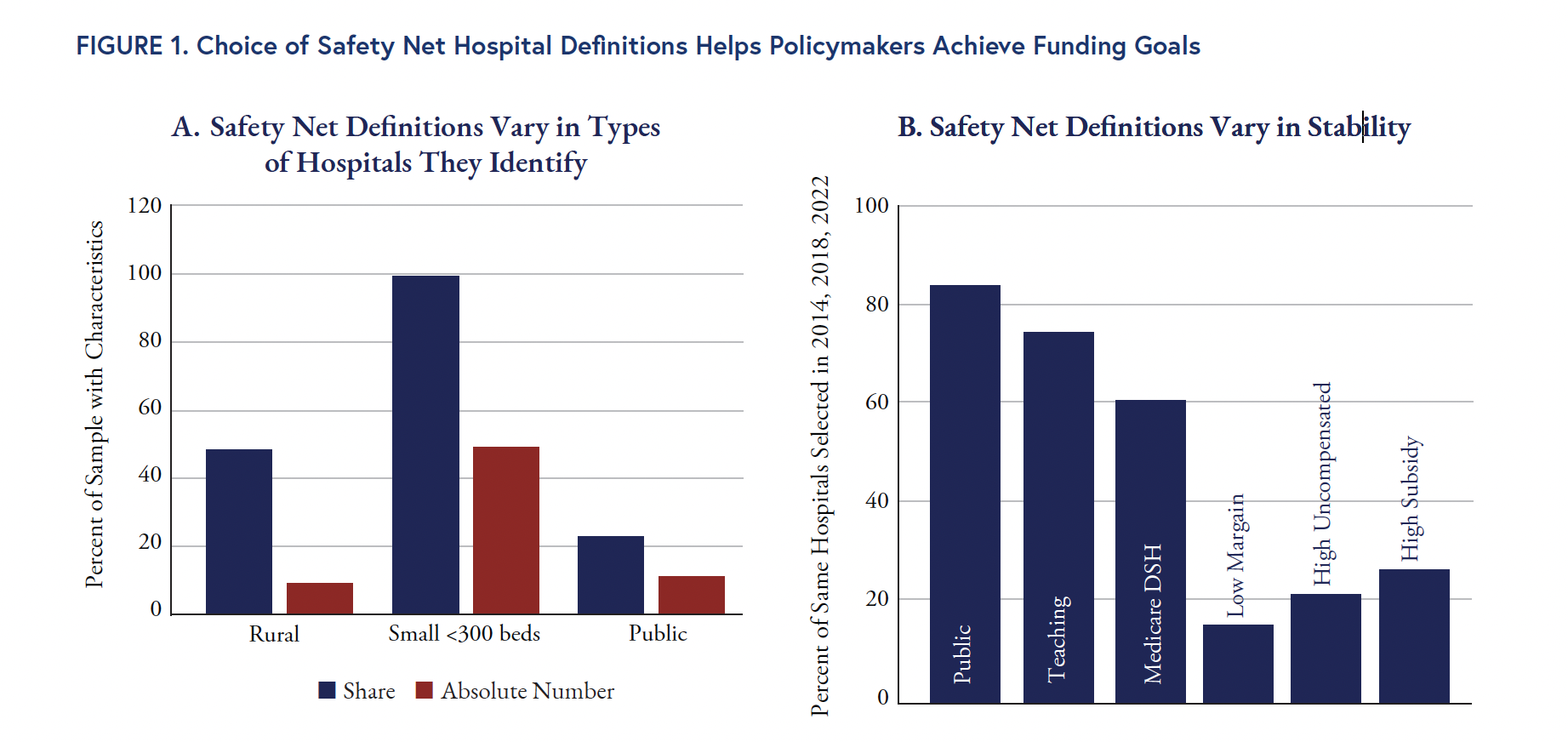

The researchers applied nine currently used or proposed hospital-level definitions to data on more than 4,500 acute-care hospitals. Different definitions captured between 992 and more than 1,300 hospitals, with varying overlap in those selected. High overlap illustrates inefficient redundancies among definitions, Chatterjee explained. Careful definition selection helps funders support their priorities, demonstrated by the study’s novel comparison of two definition approaches: estimating the share or proportion of a hospital’s total care (as inpatient days) given to low-income patients vs. the absolute amount of care provided for this group. Share measures find hospitals that dedicate most of their organization’s care to low-income patients, typically representing small, rural, public hospitals. Absolute definitions identify hospitals that provide most of the total U.S. safety net inpatient care, typically large, urban hospitals (Figure 1A).

The researchers tested definition stability using 2014, 2018, and 2022 data. The most stable definitions were public ownership, teaching status, and Medicare DSH index, identifying the same hospitals 83%-60% of the time. The least stable definition (15%) was hospital operating margin, known to fluctuate annually (Figure 1B).

Variation and instability in definitions are not necessarily problems, Chatterjee said. However, policymakers must understand this variation and transparently consider the tradeoffs of different definitions and their effects on policy goals to ensure funding effectively reaches safety net hospitals.

Different dynamic policy situations require different safety net hospital definitions. To support safety net hospitals during emergencies such as pandemics, climate-related events, or cybersecurity threats, a “big tent” definition with few exclusions may be necessary to ensure hospitals can effectively respond. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Chatterjee said, some funded hospitals may not have truly needed the support, but this tradeoff may be acceptable during a crisis. Narrower definitions may be suitable for initiatives with longer time horizons, such as designing financing strategies for uncompensated or undercompensated care.

Redundant definitions are not strategic, however, Chatterjee said. If different definitions largely identify the same hospitals, a single definition across payers could streamline data collection and outcome evaluation. This type of approach may also reduce identification and coverage challenges for individuals dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Chatterjee noted that indexes are appealing because they incorporate multiple measures, but they can overemphasize single measures. Combining multiple measures also obscures the contributions of specific components.

The researchers urge policymakers to be precise in matching safety net definitions to intended goals. Share-based definitions may be suitable for supporting rural hospitals with low patient volumes and high fixed costs. Absolute-based definitions may help large, urban hospitals get sufficient Medicaid reimbursement (Figure 1A). Policymakers can apply definitions proactively to observe the selected hospitals, clarify tradeoffs among definitions, and increase funding transparency.

Study limitations include that definitions using Medicaid data may overrepresent hospitals in states that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Those hospitals have covered patients who, in a nonexpansion state, would be uninsured and thus, excluded from Medicaid-based measures.

Chatterjee advocates for direct definitions of safety net care delivery such as measuring essential but unprofitable services that low-income people often need such as burn and trauma treatment, neonatal intensive care, and substance use care. “To me, these types of services are the heart of a safety net hospital,” Chatterjee said. “They fulfill the goal of providing expensive, needed care for people who have a hard time paying for it.”

Analyses used publicly available data and Medicare claims data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, for 2014-2022. The study also analyzed proposed and in-use measures including area-level safety net hospital measures such as Area Deprivation Index. This work was funded by Arnold Ventures (Grant 23-09141).

Source publication: Chatterjee P., Liao J.M., Amagai K., Zhao Y., Shirk T., Navathe A.S. (2025). Variation, Overlap, and Stability in Defining Safety Net Hospitals. JAMA Network Open. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.23923

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Penn LDI Debates the Pros and Cons of Payment Reform

One of the Authors, Penn’s Kevin B. Johnson, Explains the Principles It Sets Out

Six Lessons the U.S. Can Learn from Europe About Protecting Health Data Linkages

Moving from Fee-for-Service to Risk-Based Contracts Hasn’t Dramatically Changed Patient Care, Raising Questions About How to Make These Models More Effective

Equitably Improving Care for Hospitalized Kids Who Experience Cardiac Arrest Requires Hospital-Level Changes, LDI Fellows Say