Patients Face New Barriers for GLP-1 Drugs Like Wegovy and Ozempic

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

Blog Post

When LDI Senior Fellow Eric T. Roberts was reviewing a Medicaid application for an older adult in New York state, the two forms required 17 pages to be filled out. The gentleman had to provide a rent receipt, a utility bill, and every income source and asset, not just give one total figure. And these requirements aren’t unusual. New Jersey’s Medicaid application for older adults has 17 pages of demands, while Virginia’s two forms total 15 pages. Some states require older adults to fill out these forms several times a year.

It helps explain why many people lose Medicaid by making mistakes or just delay filling it out. For older adults, the effect of losing Medicaid is critical because they also lose a program that lowers drug costs—the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS)—that Medicaid provides automatically. For especially sick older adults, losing Medicaid and the drug subsidy can have deadly consequences, according to a new study led by Roberts.

Roberts and collaborators focused on one of the sickest groups on public insurance—the dual eligible beneficiaries who qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid. Nearly 1 million of this group lose Medicaid each year.

The team found that when older adults lost access to low-cost drugs after losing Medicaid, their death rate jumped by 4%, leading to nearly 3,000 more deaths during an 11-month period. Deaths rose even more among individuals with higher drug spending and those taking medications for chronic conditions such as heart disease, HIV, and chronic lung conditions.

Congress is now considering vast Medicaid cuts, up to $880 billion over 10 years, in part to finance tax cuts for wealthier people. Roberts said a cut that size would represent a 15% drop in federal Medicaid spending and would dramatically affect state Medicaid programs. Because states must balance their budgets, officials would have little choice but to scale back eligibility, lower spending on services, or install rules that limit the time people are continuously covered.

If more dual-eligible individuals lose Medicaid, there will be a cascade of harmful effects, leading to a spike in preventable deaths, Roberts said. He discusses more implications from his study, published May 14 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Roberts: I’ve long been interested in how Medicare and Medicaid serve dual-eligible individuals—a population of 13 million low-income older adults and people with disabilities in the U.S. For decades, policy experts have voiced concerns that getting coverage through two distinct programs with conflicting financial incentives can contribute to a fragmented system of care.

As I began studying these issues more deeply, I learned about the enormous amount of complexity that exists within Medicaid and assistance programs, including the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS), which are designed to help dual-eligible individuals afford care. This patchwork of programs is difficult to navigate, and too often means that individuals may not get the help they need because of administrative errors (e.g., incorrect paperwork leading to coverage termination), subtle differences in program eligibility rules, and even misaligned ways of measuring eligibility. My research focuses on understanding the consequences of that complexity and how we can simplify Medicaid and related programs to better support vulnerable individuals.

Roberts: We studied dual-eligible beneficiaries who were disenrolled from Medicaid, who, as a consequence, lost the LIS, a separate program that helps low-income Medicare beneficiaries afford medications. Most people who have LIS receive this subsidy automatically because they have Medicaid. Losing Medicaid puts these individuals at risk of being removed from the LIS, meaning they suddenly face higher medication costs.

Under LIS coverage rules, individuals losing Medicaid between January and June are removed from LIS in January (7-12 months after losing Medicaid), while those losing Medicaid between July and December are removed from LIS in January an additional year later (13-18 months after losing Medicaid). We used this fact to compare outcomes among individuals whose LIS coverage ended at substantially different times based on the exact month they lost Medicaid. We found that medication filling fell and mortality increased in months when people disenrolled from Medicaid slightly earlier lost the LIS. These mortality increases were especially pronounced among people who had higher initial medication spending and who relied on drugs to manage chronic conditions like chronic lung disease and HIV.

Roberts: Prior research showed that receiving the LIS improves medication adherence, but no prior studies had demonstrated a direct impact on health outcomes. Our study breaks new ground by showing that losing Medicaid, and with it, the LIS, increases mortality among low-income Medicare beneficiaries. This provides some of the strongest evidence to date that helping low-income Medicare beneficiaries keep Medicaid and the LIS can save lives.

Roberts: Our study focuses on dual-eligible individuals with both Medicare and Medicaid, so the findings may not generalize to all Medicaid enrollees. However, a growing body of research—particularly following Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act—has shown that gaining Medicaid is linked to reduced mortality. Collectively, this evidence underscores the importance of Medicaid in supporting access to life-saving care. It also underscores serious concerns about the health consequences of large-scale reductions in Medicaid funding, such as those now being considered by policymakers, that may lead to many individuals being kicked off the program.

Roberts: Policymakers could make changes to the Medicaid program in several areas to ensure that people who qualify for Medicaid—and thus the LIS—remain covered. These include 1) guaranteeing continuous 12-month Medicaid eligibility as a national standard, 2) simplifying the Medicaid renewal process, which can be administratively arduous for low-income older adults due to complex income and asset testing rules, and 3) helping low-income people with Medicare enroll in the Medicare Savings Programs. These are Medicaid-administered benefits that help pay for Medicare premiums and cost-sharing, and enrollees in these programs automatically receive the LIS. However, our own work found that as many as 83% of individuals who qualify for a Medicare Savings Program were not enrolled—meaning that they are forgoing substantial help with Medicare costs.

As details of Congress’s proposed budget reconciliation bill emerge, one key provision being considered would delay the implementation of a Biden-era Medicaid rule that aimed to simplify how dual-eligible individuals enroll in and keep Medicaid coverage. This, in turn, would reduce the number of low-income Medicare beneficiaries who receive the LIS. In short, this policy would move us in the opposite direction of what is needed by making it harder for low-income Medicare beneficiaries to enroll in programs that protect their financial well-being and health.

Roberts: I’m fortunate to have an ongoing portfolio of funded research looking at efforts to integrate Medicare and Medicaid coverage for dually eligible individuals. One of the goals of integrated coverage is simply to rationalize the way the system works for dually eligible individuals, with the hope that fewer individuals fall through cracks in coverage and that the programs work in a more synchronous way to coordinate care. I’m leading several studies that try to examine whether, and how, integrated care programs work as intended. I’m excited to be working with several LDI colleagues on these studies and hope to share our findings in the not-too-distant future!

The study, “Loss of Subsidized Drug Coverage and Mortality Among Low-Income Medicare Beneficiaries,” was published on May 14, 2025, in the New England Journal of Medicine. Authors include Eric T. Roberts, Jessica Phelan, Aaron L. Schwartz, Ellen R. Meara, Dominic Ruggiero, Lilly Estenson, Rachel M. Werner, and José F. Figueroa.

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

A 2024 Study Showing How Even Small Copays Reduce PrEP Use Fueled Media, Legal, and Advocacy Efforts As Courts Weighed a Case Threatening No-Cost Preventive Care for Millions

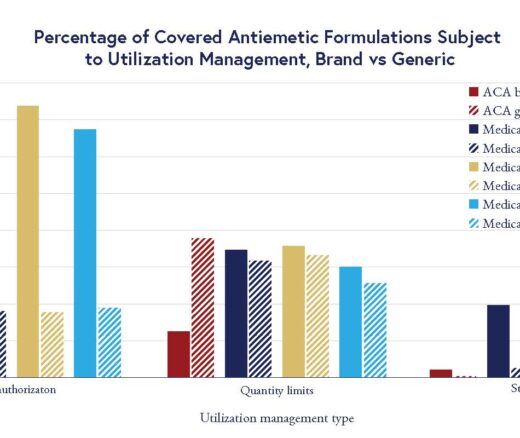

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

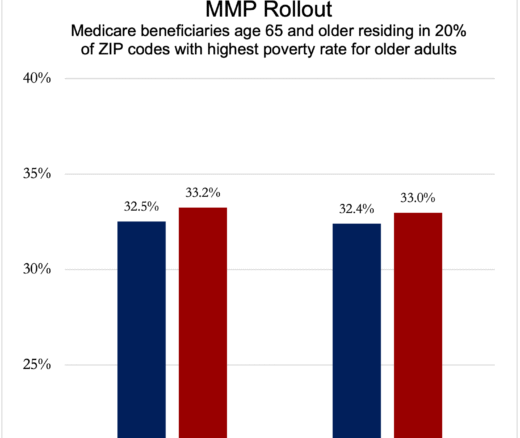

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities