Substance Use Disorder

Brief

National Variation in Opioid Prescribing and Risk of Prolonged Use for Opioid-Naive Patients Treated in the Emergency Department for Ankle Sprains

One in Four Patients Prescribed Opioids for Ankle Sprain Between 2011-2015

Annals of Emergency Medicine, July 24, 2018

Key Findings

Between 2011 and 2015, nearly one in four patients with ankle sprains were prescribed opioids in the emergency department. The overall prescribing rate declined during the study period, but varied significantly by state, ranging from 2.8% in North Dakota to 40% in Arkansas. Patients prescribed the largest amounts of opioid were nearly five times more likely to transition to continued use as those prescribed lesser amounts.

The Question

Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain. Most patients prescribed opioids for acute pain are left with extra opioid tablets, which present a risk for diversion or misuse. Furthermore, most people in the U.S. who have misused prescription opioids were given them by a friend, family member, or a doctor, and most who abuse heroin first abused prescriptions opioids. In response to the ongoing epidemic of opioid deaths, many states, insurers, pharmacy chains, and most recently the federal government have advocated supply limits on new opioid prescriptions, ranging from as little as a 3-day supply to no more than a 7-day supply. Whether these policies will reduce the number of opioid tablets entering the community, and/or limit the number of patients transitioning to long-term use, remains unclear, as do the possible unintended consequences.

To understand current patterns of opioid prescribing for an uncomplicated, self-limited condition, the authors studied a national sample of patients treated in an emergency department (ED) for an ankle sprain between 2011 and 2015. They analyzed private insurance claims for opioid-naive patients to determine patient- and state-level variation in opioid prescribing, and the association between the amount of opioid prescribed and transition to continued use (defined as filling at least four opioid prescriptions in the subsequent 30 to 180 days.) The authors standardized the amount of opioids prescribed by converting quantity of tablets and days supplied to morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs).

The Findings

The study included 30,832 patients treated in the ED for an ankle sprain who had not filled a prescription for opioids in the previous six months. The overall prescription rate declined from 28.1% in 2011 to 20.4% in 2015. The national median rate was 24.1%. Hydrocodone was the most commonly prescribed opioid (64.9%), followed by tramadol (16.2%), oxycodone (14.4%), and codeine (5.5%).

The median number of tablets prescribed per patient was 16, median total MMEs was 100, and median days supplied was three. Less than five percent of patients were given more than 225 MMEs (equivalent to more than 30 tablets of oxycodone). Patients prescribed more than 225 MMEs had a risk-adjusted probability of transition to continued use five times greater than patients prescribed 75 MMEs or less (4.9% vs 1.1%). The probability of continued use was even greater for patients prescribed higher-potency drugs (hydrocodone and oxycodone). Among patients with prolonged use, most subsequent prescriptions were not associated with the initial ankle injury, but rather other conditions, such as headache or back pain.

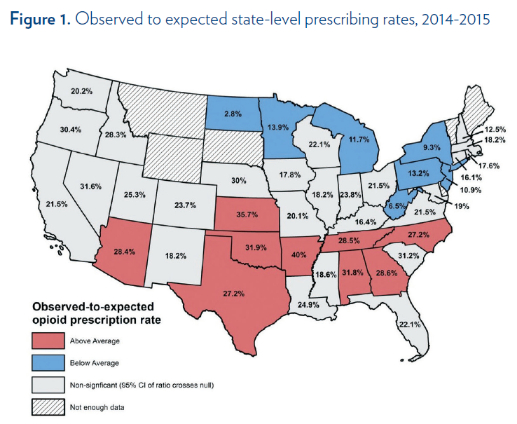

State-level prescribing rates ranged from 40% in Arkansas to 2.8% in North Dakota in 2014 and 2015. The authors compared the observed prescribing rates with expected rates, taking socioeconomic, demographic and other patient-level clinical risk factors into account. Southern states accounted for most of the higher-than-expected prescribing rates (Figure 1). Reducing excess variation in state-level prescribing could significantly reduce the number of pills entering the community. For example, reducing states’ above-average prescribing rates to the median of 24.1% would result in 18,300 fewer tablets prescribed. Similarly, if states that dispensed quantities above the median reduced prescribing to match the median (16 tablets), it would result in 32,000 fewer tablets prescribed.

The Implications

Opioid prescriptions for ankle sprain remain common and highly variable. This is concerning because ankle sprain is a minor, self-limited condition for which pain usually improves within two weeks. The findings support efforts to keep opioid-naive patients opioid naive, and to use the smallest quantities of opioid possible for treatment of acute pain.

Patients prescribed greater quantities of opioid were nearly five times more likely to transition to continued use. This points to the need to examine amounts prescribed and the risk of long-term use in other contexts in which prescriptions are much larger, such as for postoperative pain. By focusing on ankle sprains, which usually resolve quickly without development of chronic pain, this study suggests that prolonged use may have been due to other factors such as patients requesting opioids as default pain control, or development of misuse or dependence.

Significant statewide variation suggests ample opportunity to reduce excessive prescribing. Additionally, most current guidelines are written with regard to days supplied; however, the lack of specificity about how many tablets and MMEs constitute a day’s supply is problematic. A 7-day prescription could vary anywhere from one to 84 tablets, or 7.5 to 630 MMEs. Higher-risk prescriptions of 225 MMEs could still fall within 5- or 7-day supply-limit policies aimed at promoting safer opioid prescribing. Since decreasing the number of leftover tablets is critical to reducing diversion and overdoses, prescribing guidelines based on tablet quantities or MMEs may be more useful. A promising approach is implementing default opioid quantities (e.g., 10 tablets) in the electronic medical record, which has been shown to significantly shift ED discharge prescribing patterns to the default quantity and is consistent with emergency department prescribing guidelines in many states. If widely adopted, default orders have the potential to decrease the number of leftover opioid tablets in the community, but still allow clinicians to adjust the orders according to their patient’s needs. Finally, there is need for clearer guidelines for pain management strategies by indication and setting, including when opioids should not be considered the first-line treatment.

The Study

The authors analyzed claims data of 13 million privately insured enrollees in the U.S. and identified all first-time ED encounters for ankle sprains in patients older than 18 between 2011 and 2015. They excluded patients who had any other injury diagnosis, and those who had recurrent visits for ankle sprain during the study period to reduce likelihood of a severe initial injury.

The authors described variation in opioid prescription rate and characteristics at the patient and state levels and over time. They modeled patients’ expected probability of receiving an opioid prescription, adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic factors and prior history of drug abuse and mental illness. They then calculated observed to expected state-level prescribing ratios. State-level analysis was limited to those treated in 2014-2015, and excluded states with fewer than 25 patients in the study sample.

The authors quantified the number of tablets that would be prevented from entering the community from reducing excess variation by reducing states’ above-median prescribing rates to the median, and above-median prescription supplies to the median. Finally, they quantified the risk-adjusted association between initial MMEs prescribed and transition to prolonged use.

Lead Author

M. Kit Delgado, MD, MS, is an Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine and Epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania and a practicing trauma center emergency physician. He leads the Behavioral Science & Analytics For Injury Reduction (BeSAFIR) lab, which applies data science and behavioral economics for preventing injuries and improving trauma and emergency care.

This research is supported by a pilot grant from the Center for Health Economics of Treatment Interventions for Substance Use Disorder, HCV, and HIV (CHERISH), a National Institute on Drug Abuse-funded Center of Excellence (P30DA040500).