Methadone Use Rises—But Too Few People Get Opioid Medication

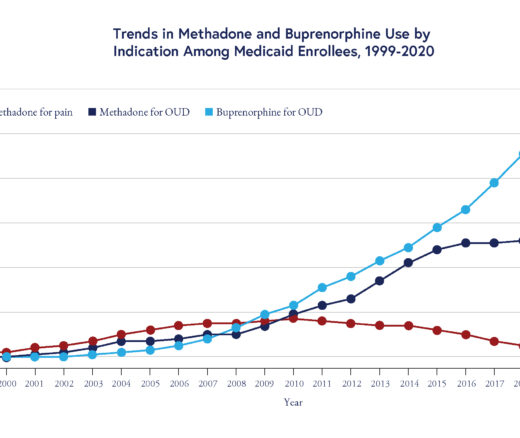

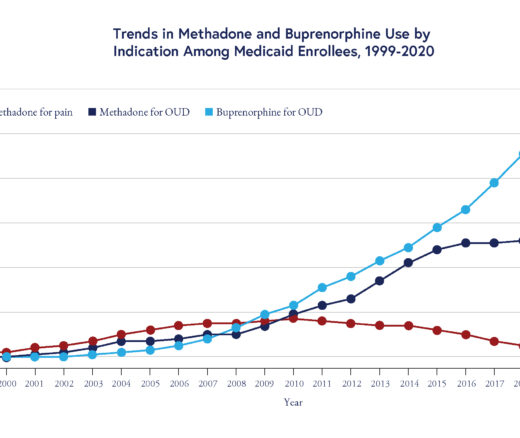

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication

Substance Use Disorder

Blog Post

Although the use of opioids in the U.S. regularly makes headlines — they were involved in nearly 81,000 estimated deaths in 2021 —the best treatments for managing opioid use disorders are widely underused. Medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD) are so effective that in 2020, Philadelphia mandated providing them at all publicly funded drug and alcohol treatment facilities.

The mandate comes with payment incentives, workforce training, and other support. This assistance is essential, but not sufficient to increase MOUD treatment. A new study in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment by LDI Senior Fellows Rebecca Stewart, David Mandell, Steven Marcus, and colleagues surveyed drug treatment center leaders familiar with the challenges of providing everyday care for opioid use disorders about what they saw as the most important barriers to offering MOUD. Summarizing the findings, Stewart says, “Nothing will change until we change beliefs.”

Beliefs about MOUD are influenced by their mechanism: They bind opioid receptors. Antagonists such as naltrexone block opioids from interacting with the receptors, preventing euphoric effects. Agonists such as methadone and buprenorphine bind receptors to reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms without the euphoria of oxycodone, heroin, or fentanyl. Stewart and colleagues heard from community partners such as nonprofit organizations that provide behavioral health services for the city, and from interviewing leaders of drug treatment organizations, that negative ideology about the medications, particularly agonists, create an “intervention stigma” around MOUD.

Nonetheless, policymakers at the highest level advocate for MOUD. In November, Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, called for easing regulations around methadone. Currently, it must be prescribed through specialized treatment facilities.

To determine if beliefs about MOUD are linked to providing the medication to people with opioid use disorders, Stewart and colleagues surveyed leaders of 45 publicly funded substance use disorder treatment centers in Philadelphia that serve a total of nearly 79,000 patients. Questions were about workforce, organization, funding, regulations, and beliefs about providing MOUD at their center. The researchers analyzed the findings by dividing centers into high and low adopters, with high adoption defined as more than half of clients with opioid use disorder receiving MOUD.

Most leaders endorsed financing for physician time, lab tests, and medications as a barrier to implementing MOUD at their treatment center. However, these financial barriers did not distinguish between high and low adopters. Instead, belief-related barriers were significantly different among leaders of organizations with low and high MOUD use, with survey respondents from low-adopting centers significantly more likely to endorse 9 of 10 MOUD-belief barriers.

Belief barriers included that MOUD causes cognitive impairment that interferes with treatment or have adverse effects on bones and teeth. Low MOUD-adopting center leaders also endorsed concerns about selling the agonist buprenophine or mixing it with other drugs to get high. Other endorsed beliefs were that patients aren’t interested in MOUD and that providing MOUD is “substituting one drug for another.”

The Philadelphia mandate allows facilities to not provide MOUD directly but document linking patients to external programs. Low-adopting centers were significantly more likely to do this, suggesting that eliminating this option could move more centers to offer MOUD directly to patients. Standardizing how clinicians present treatment options for opioid use disorder could reduce differences between low-adopting and high-adopting facilities. Changing attitudes about MOUD will also require interventions at the patient and family level, since many leaders of low-adopting centers say their patients aren’t interested in MOUD.

Beliefs about lack of evidence supporting the clinical effectiveness of MOUD did not distinguish between leaders of high-adopting and low-adopting treatment centers. Stewart notes that this result and her experience visiting community treatment centers and interviewing their leaders suggest that showing them research evidence supporting MOUD does not convince them to provide it.

Instead, evidence on clients from their own organization who use MOUD would be more relevant. In particular, since treatment center leaders interact with their patients daily, narratives and testimonials from people who have experienced opioid use disorder and MOUD, perhaps even from patients of the low-adopting treatment facilities, would be most meaningful at showing the impact of MOUD.

The study, Not in my Treatment Center: Leadership’s Perception of Barriers to MOUD Adoption, was published in Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment on October 13, 2022. Authors are Rebecca E. Stewart, Nicholas C. Cardamone, David S. Mandell, Nayoung Kwon, Kyle M. Kampman, Hannah K. Knudsen, Christopher W. Tjoa, Steven C. Marcus.

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication

LDI Fellows Used Medicaid Data to Identify Individuals at Highest Risk for Cocaine- and Methamphetamine-Related Overdoses, Paving the Way for Targeted Prevention

Penn and Four Other Partners Focus on the Health Economics of Substance Use Disorder

Penn Medicine’s New Summer Intern Program Immersed Teens in Street Outreach Techniques

LDI Experts Offer 10 Solutions to Get More Help to Seniors With Addiction

More Flexible Methadone Take-Home Policy Improved Patient Autonomy