Only One in Four High-Risk Rural Births Get Appropriate Hospital Care

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

News

Imagine how it was for Linda Aiken, PhD, RN, an LDI Senior Fellow, and world-renowned University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing researcher, when the largest project of her career collided with the COVID-19 pandemic:

You and your teams of hundreds of health care managers, staffers, clinicians, and researchers in 132 hospitals and nine universities across the U.S. and Europe had worked for 10 years to organize the largest hospital randomized controlled trial and implementation science project of its kind ever attempted. After a decade-long gauntlet including large-scale descriptive research documenting the importance of good hospital work environments for patient outcomes in European hospitals, successfully competing for EU funding, recruiting 132 hospitals, and addressing administrative and logistical challenges, the project’s official start date approached with a sense of can-do camaraderie and triumph. And then, the launch happened — in January, 2020, just weeks before the coronavirus rose up to engulf both continents — shutting universities, snarling trans-Atlantic transportation, and catastrophically disrupting the internal operations of hospitals everywhere.

Virtually overnight, Aiken and Penn Nursing’s Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research (CHOPR)’s massive Magnet4Europe (M4E) project began grappling with a previously unthinkable tangle of new difficulties spawned by the global disease outbreak.

“In the very beginning, we had no idea the pandemic was going to go on for years, or how pervasive it would be,” remembered Aiken. “In March, 2020, we had our first Magnet4Europe in-person meeting in Washington, D.C. with the participating U.S. magnet hospitals, and there was so much enthusiasm, but also rising concern as some hospitals wouldn’t allow their nurses travel to D.C. because of the mounting number of COVID admissions. The day before I traveled back to Philadelphia, Penn announced its own closure. From then on, for Magnet4Europe, it was rapidly spreading pandemic restrictions everywhere and creative thinking all around about whether or not something as large and complex as this could be continued in a virtual way.”

The magnet program is essentially a framework and blueprint for the sweeping internal reorganization of a hospital’s clinical operations, staffing policies, internal communication practices, management philosophies, top-of-license teamwork integration, and problem-solving systems. The overall goal of the evidence-based intervention is to create and maintain a clinical working environment that systematically minimizes clinician stress and burnout, and improves patient care.

The Magnet4Europe project is a European test of the U.S. Magnet® Recognition Program that grew out of Aiken’s research in the early 1980s. Formalized as a system owned by the American Nurses Association’s American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), the first U.S. “magnet” hospital was certified in 1994. There are now 566 certified magnet hospitals in the U.S., including all six hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania Health System, and 14 others outside the U.S. including two in Europe.

The “magnet” in “magnet hospital” comes from a 1980s nursing colloquialism. It characterizes hospitals that have high quality working conditions that, like magnetism, attract and keep nurses who want to work there. Aiken’s original 1980s landmark studies found that aside from higher job satisfaction for nurses, the working environment inside such hospitals produced lower levels of patient mortality.

For much of its history the program was named the “Magnet Hospital Recognition Program for Excellence in Nursing Services,” and was almost exclusively associated with nursing. However, after adopting it, hundreds of hospitals found that implementation of the magnet framework altered the entire clinical environment for the better. The program has since dropped the “Nursing Services” reference in its name and is now widely recognized as a gold standard of overall clinical organizational principles.

“Those of us originally involved in it always thought it was bigger than nursing,” said Aiken. We never had nursing in the title when we did the first study under the auspices of the American Academy of Nursing. That was a decision of the American Nurses Association. Back then, there wasn’t a real recognition of why this was about more than nursing. But to us, it was always evident because the magnet model is an institution-wide intervention. You couldn’t possibly do it without the agreement of top management and physicians.”

Indeed, when the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation funding initiative put up the money for M4E, it officially titled the program and goal as “Improving Mental Health and Wellbeing in The Health Care Workplace.” The four-year project is designed to improve overall hospital working environments in 65 facilities in England, Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Norway and Sweden. Each of those European hospitals is “twinned” or partnered with a certified U.S. magnet hospital that provides support and encouragement grounded in its own experience of becoming and operating as a magnet facility.

For instance, each of Penn’s six magnet hospitals are twinned with different European hospitals undergoing the magnet intervention — two in Belgium, three in Germany, and one in Ireland.

“There are Magnet manuals that spell out the intervention in great detail, the operational route to achieving changes, and the kind of evidence that shows you are accomplishing that,” said Aiken. “But it’s not all that easy — having a critical mass of people around you who have lived and breathed the Magnet® model really helps a new hospital understand how it all works and what the concepts mean.”

The overall Magnet4Europe initiative is led by Penn Nursing’s CHOPR and Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (KUL), the largest university in Belgium. Aiken is Co-Director of the initiative with KUL’s Professor Walter Sermeus, PhD, RN. A team at the University College Cork UCC lead by Jonathan Drennan, PhD, MEd, RN, Chair of Nursing and Health Services Research, is collaborating with CHOPR to provide the intervention. Other university partners in Europe are leading different aspects of the research and providing country-level assistance to their participating hospitals.

The project is both an implementation of the Magnet® model in European hospitals as well as a randomized controlled trial to determine how well the model improves clinician wellbeing.

Originally, transatlantic commuting was to play a large role in M4E’s sprawl of operations. Its teams and administrators looked forward to building relationships and conducting work in-person across the far-flung network of hospitals. But that became just one of the M4E elements impacted by COVID-19.

“It quickly got more difficult in other ways as well as the pandemic took hold,” said Aiken. “For instance, all the hospitals had to take this project through their human subject committees and that became more complicated because COVID projects were prioritized and we got delayed there.”

Meanwhile, key M4E managers in some hospitals were suddenly pulled away from those administrative duties and moved back into emergency clinical service in the overflowing COVID wards.

“It’s been challenging to keep something this big really going forward during the COVID pandemic,” said Aiken. “Part of the original plan was to have ongoing in-person learning collaboratives to showcase the best practices and give all the sites the opportunity to communicate across the countries and continents. But the U.S. hospitals have never met in person with the European side hospitals and the European hospitals have never been able to meet among themselves. All the participating countries have hung on — although we did lose five European hospitals but no U.S. hospitals — which seems something of a miracle in the middle of the pandemic.”

“We switched to monthly virtual meetings to bring together all the hospitals across countries,” said Aiken. “But that has been very time consuming for CHOPR at Penn and our partners at University College Cork in Ireland who host the events on their virtual learning platform.”

As the first wave of the pandemic continued to intensify across Europe in 2020, the European Commission’s funding agency launched a review of Magnet4Europe operations to determine if funding should continue, given the extraordinary operational difficulties created by COVID-19.

The European Health and Digital Executive Agency’s final December, 2021 report found that Magnet4Europe “had to deal with multiple adjustments because of the situation, and despite the probability that the project could have been completely derailed by the crisis, the consortium has done remarkably well in limiting the impact.”

“That report gave everybody a boost,” said Aiken. “It was a validation that we were succeeding despite the pandemic. Afterward, the EU told us we had been the most vulnerable grant in the cycle because Magnet4Europe was so big and involved direct care and hospitals that were in the midst of the COVID crisis — it had made them wonder if we could possibly succeed. But we did.”

Underscoring an irony of the situation, the report also noted that the unprecedented levels of stress and burnout among European hospital workers involved in providing COVID-19 care, “make this type of project even more important. A concrete integration in the project of COVID-related issues may enhance the impact of the project from multiple perspectives.”

Aiken agreed. “I think every nurse everywhere recognized that the problems M4E was trying to solve predated the pandemic and were worse in a pandemic,” she said. “Just as the EU Commission report indicated, the pandemic actually helped in identifying the seriousness of the need to fix the problem of high rates of burnout and dissatisfaction among nurses and doctors. It brought the whole thing very alive for everyone.”

“That was the reason pretty much everyone remained committed to M4E goals — because the issue of clinician burnout and depression was more serious in countries outside the U.S.,” said Aiken. “Here in the U.S., we have plenty of nurses. These other countries don’t have anywhere near that supply and they’re much more sensitive to losing people. So the commitment to doing the project was strengthened even more because of the pandemic, even though the practical daily operational challenges of taking care of the COVID patient load were there and very real.”

Looking ahead, M4E hopes to hold its first, in-person project-wide meeting in May — a two-day Learning Collaborative in Cork, Ireland.

“Everyone in Magnet4Europe certainly hopes that COVID abates enough for person-to-person exchanges to take place,” said Aiken. “There is an amazing amount of energy, given two years of virtual collaborations, and 132 hospitals are chomping at the bit to visit one another,” Aiken said.

Looking beyond the end of M4E in December, 2023, Aiken eyes the potential of other research projects elsewhere around the planet where, in the last three decades, she and the CHOPR team have conducted clinical work environment improvement studies in more than thirty countries across six continents. These include China, Russia, Armenia, South Africa, 15 European countries, Japan, Thailand, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and Chile.

We asked Aiken if anyone had ever estimated the total number of clinicians and patients she and the Nursing School CHOPR team’s work had touched in establishing new standards to improve clinical work environments around the world.

“I’ve never tallied that up,” Aiken said, “but it would certainly be in the millions. The work involved the whole United States — throughout the hospital sector, nursing homes, and home care. And then we’ve also had our research directly in 30-some other countries. When you add that all up, that’s many millions of people that our research has affected.”

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

Former CMMI Leader Liz Fowler Cites Rigid Federal Scoring Rules and Bureaucratic Impatience for Pilot Failures

A Major European–U.S. Hospital Study Finds That Changing How Hospitals Are Organized Reduces Burnout and Turnover While Improving Care Quality

An LDI Fellow Who Helped Architect the ACA Highlights Progress on Primary Care Payment Reform and the Expansion of Site-Neutral Reimbursement Policies

Penn LDI Senior Fellow Dominic Sisti Cites “Alarming Levels”

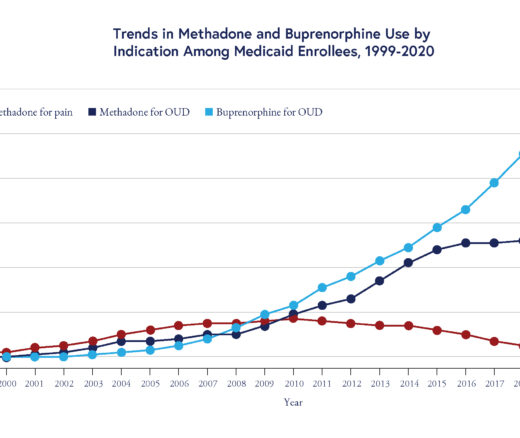

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication