How Playing Games May Save People’s Lives

The Growing Use of Gamification in Health Motivates People to Exercise More and Take Other Actions to Improve Their Physical Well-Being

Improving Care for Older Adults

Blog Post

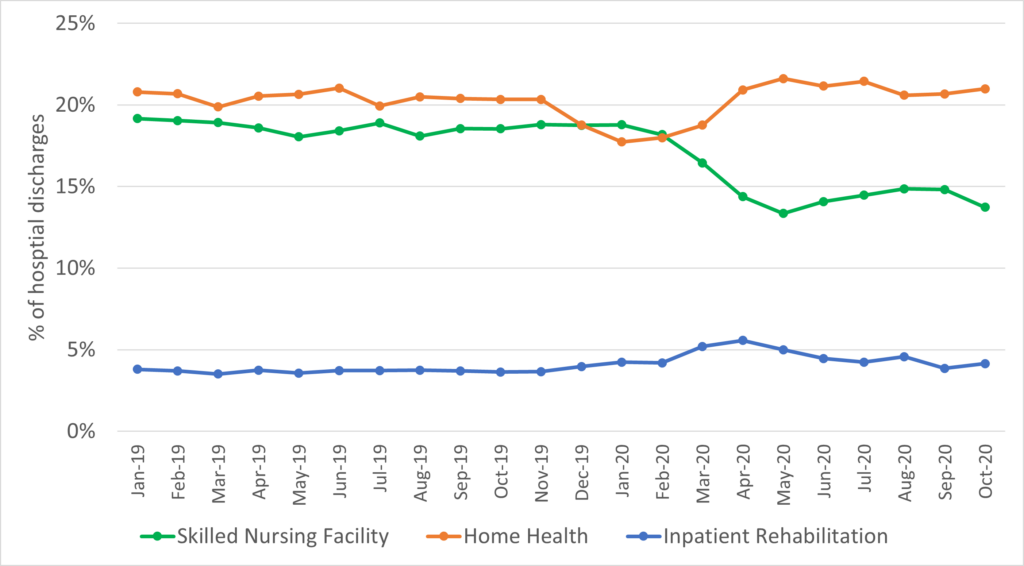

In a new study, Rachel Werner and Eric Bressman document unprecedented shifts in post-acute care during the pandemic, with significant and sustained declines in the number of hospitalized patients being discharged to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). As a result, SNFs took a significant financial hit, as total payments to SNFs decreased to less than half of their prepandemic levels, from an average of $42 million per month in 2019 to $19 million in October 2020.

While health care utilization dropped across the board in the early days of the pandemic, the decline seen in SNFs is unique in that it has not rebounded. The consequences for the nursing home industry could be dire if these trends continue. Post-acute care admissions represent a small percentage of all nursing home admissions, but account for a major source of revenue for nursing homes that nursing homes rely on to stay afloat. Daily reimbursements for post-acute care (covered by Medicare) are considerably higher than the daily rate for long-term care stays (often covered by Medicaid).

Werner and Bressman used a multi-payer database that included more than 975,000 hospital discharges for patients who were 65 years or older. They found that post-acute care use declined in all settings early in the pandemic, including the three most common sites of post-acute care (home with home health care, SNFs and inpatient rehabilitation facilities). However, while the use of home health care and inpatient rehabilitation rebounded quickly, the use of SNFs did not. The percentage of patients discharged to SNF had the steepest decline, from an average of 19% of discharges in 2019 to 14% in October 2020.

The authors note that the shift away from institutional post-acute care began before the pandemic, as Medicare and other payers targeted the high use and cost of these facilities. This has put the squeeze on a critical part of nursing homes’ revenue. Medicare payment for post-acute care services is an important source of nursing home revenue and is often used to cross-subsidize care for long-stay residents with inadequate payment from Medicaid. And, at the same time, occupancy rates have declined for long-stay nursing home residents, as states have shifted Medicaid-funded care out of nursing homes and into people’s homes. The pandemic accelerated these trends, potentially undermining the fragile fiscal health of the nursing home industry.

Because of declining admission and occupancy rates for both post-acute and long-term care, one industry analysis concludes that nursing homes could lose $94 billion over the course of the pandemic, and that 2,000 of them could close without financial assistance. A large influx of public funds during the pandemic has cushioned the immediate blow. But, if admission rates to SNFs don’t rebound, the long-term outlook for nursing homes may be bleak.

We don’t yet know whether these trends will continue beyond the pandemic, and the full implications for patients and families if post-acute care continues to shift to home, as unpaid caregivers may have to absorb the care that was once provided by Medicare-paid providers. But the impact on the nursing home industry is likely to be large and disruptive, with almost certain nursing home closures.

In a Health Affairs blog post last year, Werner and co-author Courtney Harold Van Houtven noted the need to rethink post-hospital care at home, and to prepare for a future in which more intensive rehabilitative care can be provided at home. They pointed out the need to pay family caregivers and pay health professionals to support caregivers in delivering this care in the home. They concluded:

Covid-19 gives us the opportunity to reimagine what optimal post-hospital care might look like after the pandemic is over, an opportunity we shouldn’t squander. There is a safe alternative to nursing home-based post-acute care, one that is favored by many patients and their families and might even cost us less. We can help people recover at home.

In this reimagined future, we will need to re-evaluate the underlying financing and payment of nursing homes to account for significant reductions in post-acute care. What does this mean for the delivery of long-term care, and the role of nursing homes? We can’t yet know the contours of the change, but it is likely that the nursing home industry is in for a rough ride.

The study, Trends in Post-Acute Care Utilization During the COVID-19 Pandemic, was published online in JAMDA on September 7, 2021. Authors include Rachel M. Werner and Eric Bressman.

The Growing Use of Gamification in Health Motivates People to Exercise More and Take Other Actions to Improve Their Physical Well-Being

Pa.’s New Bipartisan Tax Credit is Designed to be Simple and Refundable – Reflecting Core Points From Penn LDI Researchers Who Briefed State Leaders

Focusing in on Some of Health Care Policy’s Most Urgent Issues

Highlighting 10 Ways LDI Fellows Put Their Research Into Action

From AI-Powered Public Health Messaging to Stark Divides in Child Wellness and Medicaid Access, LDI Experts Highlight Urgent Problems and Compelling Solutions

An LDI Expert Offers Three Recommendations That Address Core Criticisms of the ACA’s Model