Health Care Access & Coverage | Health Equity

Blog Post

Primary Care Access for Philadelphia’s Medicaid Population

Analysis shows variation in supply, appointment availability, and wait times across the city

Following Medicaid expansion in Pennsylvania in 2015, more than one in five non-elderly adults in Philadelphia are now covered by Medicaid. This population faces unique challenges with accessing primary care, including fewer providers accepting Medicaid patients.

We welcome the City of Philadelphia’s efforts to better understand and address these challenges. Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health is today releasing a report on access to primary care, which includes a specific look at the city’s Medicaid population. Our team contributed data and analyses to this report.

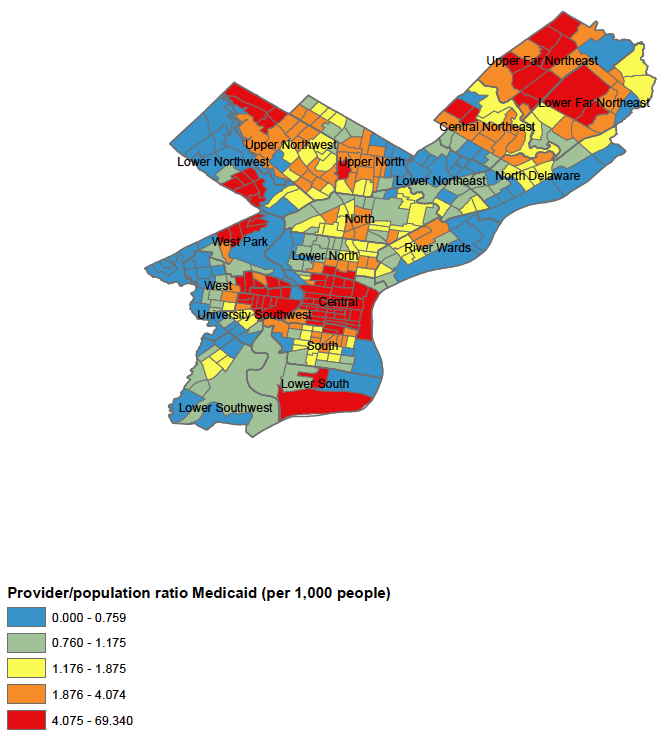

Our analysis found that the ratio of primary care providers accepting Medicaid to the number of Medicaid beneficiaries was relatively stable between 2014 and 2016 – when Medicaid expansion happened. However, we found large variation in this measure across Philadelphia neighborhoods. Some census tracts had virtually no primary care providers accepting Medicaid in 2016, while others had as many as 69 primary care providers accepting Medicaid per 1,000 Medicaid beneficiaries living in that tract.

Central Philadelphia and University City – home to major health systems – had the largest supply of primary care providers accepting Medicaid. Selected pockets in the far North and Northwest were also well supplied. Lower supply areas were scattered across the city, but concentrated in the West, Southwest, and Lower Northeast sections of the city.

To help get a better picture of patient experience, we also analyzed data on primary care appointment availability for non-elderly adults with Medicaid, who were targeted by the expansion. We used data from a 2014 and 2016 audit study in which researchers called the offices of doctors that accept Medicaid, said they were a Medicaid patient, and requested a new patient appointment.

We found that just two-thirds of these primary care practices offered a new patient appointment to Medicaid callers (compared to 85% for privately insured callers contacting practices). When an appointment was offered to Medicaid callers, the wait was on average 18 days. Appointment availability was lowest in Central (45%) and in South/Lower South Philadelphia (48%), and highest in the Lower North (91%), Lower Northeast (88%), and North Philadelphia (87%). Wait times also varied across the city: they were lowest in the River Wards (7.8 days), and over three times higher in the South/Lower South (26.6 days). Like with the measure of supply, appointment availability did not change significantly between 2014 and 2016 despite the Medicaid expansion in 2015.

Our results clearly show that there’s large variation in where Medicaid primary care providers are located in the city, but it is hard to say how this is experienced by an individual Medicaid beneficiary. When people need medical care, there are many reasons to choose a provider other than how close the office is to your home. For instance, a person may want to choose a provider they already know and trust, a provider recommended by a friend or family member, or one that is more accessible by public transit.

So what do these results tell us? First, some neighborhoods have a lot more primary care providers that accept Medicaid than others. Second, Medicaid beneficiaries have fewer primary care provider choices than the privately insured since not all providers participate in Medicaid, and just two-thirds of those participating offered new patient appointments. Third, we did not find evidence that the supply of providers who accepted Medicaid or access to primary care for Medicaid beneficiaries changed greatly after the Medicaid expansion.

We welcome Commissioner Farley and the City’s attention to the critical issue of primary care access, and recommend focusing attention on areas where supply or appointment availability suggests an access problem. Other cities should follow Philadelphia’s lead and take a hard look at gaps in their primary care delivery systems, and whether those covered by Medicaid are adequately served. Health coverage on its own is not enough. Unless we address problems of primary care access, we won’t make the health gains we ought to see from an expanded Medicaid program.