Patients Face New Barriers for GLP-1 Drugs Like Wegovy and Ozempic

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

Blog Post

As the U.S. population ages and Medicare enrollment increases, Medicare spending will rise from under $900 billion in 2019 to $1.5 trillion in 2029. Cost-controlling strategies from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in the face of this growth include Medicare Advantage (MA) and the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP).

MA pays private insurers per beneficiary to manage cost-effective care that keeps members healthy. MSSP encourages high-quality, low-cost care by sharing cost savings with health care systems that create an Accountable Care Organization for their fee-for-service Medicare recipients.

Head-to-head comparisons of the programs are complicated because MA and MSSP enrollees differ, for example, in overall health and income. A new study by LDI Senior Fellows Ravi Parikh, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, and Amol Navathe compared MA and MSSP costs, adjusting for detailed clinical risks of enrollees.

We asked lead author Dr. Parikh five questions about the study. Answers were edited for length and clarity.

Spending was about 25% higher for MSSP than for MA beneficiaries in our evaluation of more than 15,000 beneficiaries between 2014 and 2018. We used a unique linkage between claims and electronic health record data from a large academic health system in Louisiana that allowed us to account for detailed clinical risk factors, including from labs and vital signs, that we typically can’t control for in claims-based analysis. Practice patterns and quality of care were largely similar between the two groups.

Given these findings, we concluded that most spending differences between MA and MSSP may be due to unmeasured socioeconomic status differences between MA and MSSP populations, suggesting the need to align program designs and account for social determinants of health.

We considered an additional provider-based charge for hospital services under MSSP, and common enrollment changes such as a tendency for MA beneficiaries to disenroll at the end of life when they enroll in hospice via fee-for-service Medicare.

We took great care to account for differences in clinical characteristics between MA and MSSP enrollees by grouping them by common conditions of hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and chronic kidney disease, and matching them between beneficiary groups. We accounted for differences in income by adjusting for residence zip code, and for variation in care by studying members within a single health care system and adjusting for primary care physician.

Even with these considerations, spending differences persisted. Given this, we felt it likely that acute care utilization resulting from unmeasured individual-level differences in social determinants of health may play a role in spending differences.

Prior analyses suggested that differences in unmeasured socioeconomic and clinical characteristics may complicate risk adjustment and be responsible for higher MSSP spending.

Our findings reinforce the cost-savings difference between MA and MSSP and show physician-level practice patterns or beneficiaries’ clinical risks were unlikely to be the reason. This suggests that, regardless of risk adjustment, underlying social determinants are key to rectifying payment gaps between the two programs.

One key recommendation is for CMS to align the program design of MA and MSSP to prevent disincentives to MSSP participation and better account for enrollees’ behavioral and social factors.

This recommendation is based on our finding that nonclinical risk factors were the reason that health system participation in MA was less costly than MSSP. Enrollees’ clinical characteristics accounted for only a small part of cost differences, so adding this information to CMS risk adjustment models may not be worth the effort. Risk adjustment based on currently unmeasured behavioral and social factors may be more accurate and mitigate MA-MSSP cost disparities.

Our study may also argue for more vertical alignment of fee-for-service-based settings, meaning unifying services in one organization. Under vertical alignment, health systems receive a full, fixed payment to care for MA enrollees, which may provide a stronger incentive to reduce spending.

Our group has started to evaluate key behavioral initiatives to reduce costs, including a large effort with a payer to shift medical procedures to more value-conscious providers. These initiatives have major implications for Medicare spending.

Additionally, we are looking at exactly how commercial and Medicare spending changed during the pandemic, and how COVID-19 may have influenced spending benchmarks set by federal and state alternative payment models.

The study, “Evaluation of Spending Differences Between Beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and the Medicare Shared Savings Program,” was published in JAMA Network Open on August 23, 2022. Authors are Ravi B. Parikh, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Colleen M. Brensinger, Connor W. Boyle, Eboni G. Price-Haywood, Jeffrey H. Burton, Sabrina B. Heltz, and Amol S. Navathe.

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

A 2024 Study Showing How Even Small Copays Reduce PrEP Use Fueled Media, Legal, and Advocacy Efforts As Courts Weighed a Case Threatening No-Cost Preventive Care for Millions

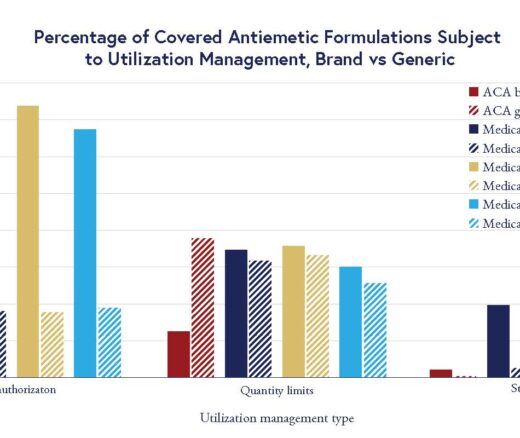

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Research Brief: Shorter Stays in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Less Home Health Didn’t Lead to Worse Outcomes, Pointing to Opportunities for Traditional Medicare

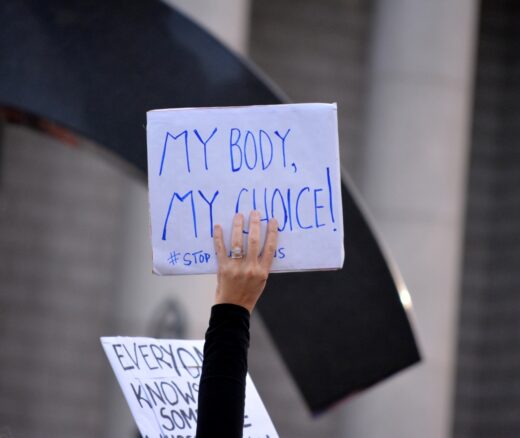

How Threatened Reproductive Rights Pushed More Pennsylvanians Toward Sterilization