Acupuncture Could Fix America’s Chronic Pain Crisis–So Why Can’t Patients Get It?

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

Blog Post

Rural hospitals have been in “a slow-burning crisis for decades,” says LDI Senior Fellow Paula Chatterjee. Over 130 facilities have closed since 2010. That has left about 2,250 remaining rural hospitals out of about 5,000 facilities nationwide.

Rural hospitals have been closing at a faster rate in recent years. And when a closure occurs, it typically causes other local providers to shut down like those in primary or specialty care. These gaps might be partially filled by federally qualified health centers, but gaps remain after the closures occur.

Chatterjee, an Assistant Professor of General Internal Medicine at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, recently wrote about the “Causes and Consequences of Rural Hospital Closures” for the Journal of Hospital Medicine. She discussed the plight of rural hospitals in more detail below.

It’s hard to know the exact causes, because so much is changing in rural communities at the same time. Teasing apart which factors are causal and which are just along for the ride is a tough task. We know that rural hospitals in states that did not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) were more likely to close in the post-ACA era. Other things that might be linked to a higher likelihood of closure include the facilities’ precarious finances as well as declining economic conditions in broader rural communities. Among the rural hospitals that have closed in recent years, a larger share of them were for-profit.

Another factor is that rural patients are increasingly bypassing their local hospital to seek care at a facility located farther away. These bypass patterns may be driving lower occupancy rates for rural hospitals. The reasons for this behavior are unclear, but may be related to perceptions of better quality if they travel farther or concerns that local hospitals might not offer the care they need.

Rural hospitals are typically much smaller. They have lower occupancy rates and are more susceptible to financial volatility. As a result, rural hospitals typically have less than half the median profit margins of urban hospitals.

We don’t know yet. By some counts, 21 rural hospitals have closed since the beginning of COVID-19 which doesn’t appear to be a big departure from pre-pandemic trends. Others have even made the case that rural hospitals may have been uniquely able to withstand some of the pandemic-related financial pressures due to the multidimensional roles already played by staff members and the strong community-hospital relationships that were built before the pandemic set in.

There’s some evidence to suggest that rural hospital closures were more likely to occur in counties with larger shares of non-white residents. This is the context of rapidly changing demographics and migration patterns in rural America, which is becoming increasingly represented by racial and ethnic minority populations. There’s also prior work showing that rural counties with higher proportions of non-Hispanic Black populations were more likely to lose access to obstetric care. Taken together, these trends raise concerns that the populations left behind may be overrepresented by communities of color.

There are over 20 different programs run by the Department of Health and Human Services designed to financially bolster rural hospitals. Those facilities also get support in the form of local or state government subsidies and can benefit from different types of provider taxes. Despite the proliferation of these supports, these hospitals have continued to struggle financially.

If we want to bolster rural health care, we have to bolster rural communities more broadly. Decades of reforms focused on health care payment and its associated infrastructure have not eased the fundamental challenges that rural communities face related to declining economic opportunity and growing socioeconomic disadvantage.

The goal of health care is to improve health. Designing policies that focus on the upstream drivers, like improving economic and employment conditions, may prove to be more fruitful since they have far more to do with driving health outcomes than health care itself.

Bolstering rural health care delivery should remain a priority while we focus more on the upstream factors. In that vein, I think novel policies like the Rural Emergency Hospital Program and the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model are creative approaches to rethink how rural health care can be delivered to meet the challenges of their communities.

The Rural Emergency Hospital Program will allow rural hospitals to convert to emergency departments without providing any inpatient care. The goal is to preserve access to emergency care without exposing rural hospitals to the potentially unnecessary fixed costs of running an inpatient unit that is rarely occupied.

The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model began in 2019 and is designed to fundamentally change the way rural health care is funded. By giving hospitals a “global budget,” the program seeks to provide financial predictability and stability for these hospitals so they’re able to transform the way they deliver patient care to meet patients’ needs. In reality, this has come in the shape of scaling up telemedicine capabilities or developing community health worker programs.

What’s great about these approaches is that they’re trying to meet rural communities where they are. They offer financial support but permit enough flexibility in how they are implemented to meet the needs of different communities. It will be exciting and important to see how these programs evolve in the coming years.

The full paper, “Causes and Consequences of Rural Hospital Closures,” was published on October 3, 2022 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine by Paula Chatterjee.

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Research Brief: Shorter Stays in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Less Home Health Didn’t Lead to Worse Outcomes, Pointing to Opportunities for Traditional Medicare

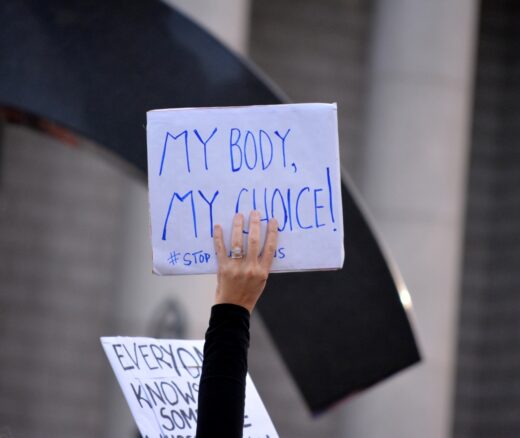

How Threatened Reproductive Rights Pushed More Pennsylvanians Toward Sterilization

Abortion Restrictions Can Backfire, Pushing Families to End Pregnancies

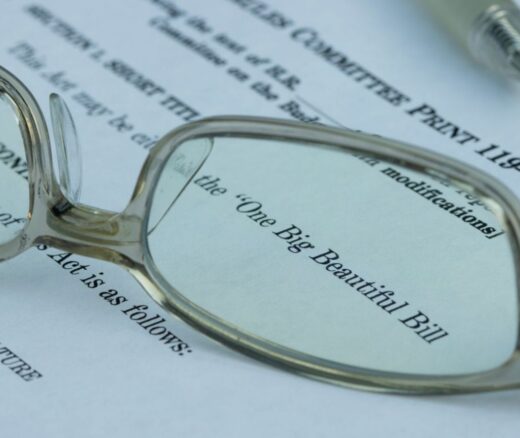

They Reduce Coverage, Not Costs, History Shows. Smarter Incentives Would Encourage the Private Sector