How Medicaid Cuts Could Force Millions Into Nursing Homes

If Federal Support Falls, States May Slash Home- and Community-Based Services — Pushing Vulnerable Americans Into Nursing Homes They Don’t Want or Need

Blog Post

Unprecedented public-private partnerships, in scope and magnitude, and remarkable work in science and vaccine development, has resulted in safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines. These vaccines have changed the trajectory of the pandemic, giving us the potential to reduce infections and the number of hospitalizations and deaths. The use of these products in the first five months of 2021 saved an estimated 140,000 lives in the U.S. alone.

Even as we remain embroiled in this pandemic, we can take stock of six lessons learned “upstream” (i.e., the development, manufacture, and regulatory approval of vaccines) and “downstream” (i.e., the broad deployment of vaccines) that can inform and improve our preparedness for future pandemics.

Vaccine candidates fail often, usually in early stages of pre-clinical and clinical development. In a pandemic, investing in a broad range of vaccine platforms increases the probability a single vaccine candidate will cross the proverbial finish line quickly. While it’s difficult to capture the global investments into research and development, we know the scale is in the billions. The U.S. alone has invested over $12 billion in six programs (with AstraZeneca, Janssen, Moderna, Novavax, Pfizer/BioNtech and Sanofi/GlaxoSmithKline) based on three platforms: mRNA, adenovector, and recombinant protein technology. This financial and technical support allowed companies, particularly smaller ones, to rapidly engage in development and manufacturing activities. Continued investment in non-pandemic times across the sciences that comprise vaccinology—basic science, immunology, delivery strategies, manufacturing, and clinical evaluation—are critical to preparedness and should continue.

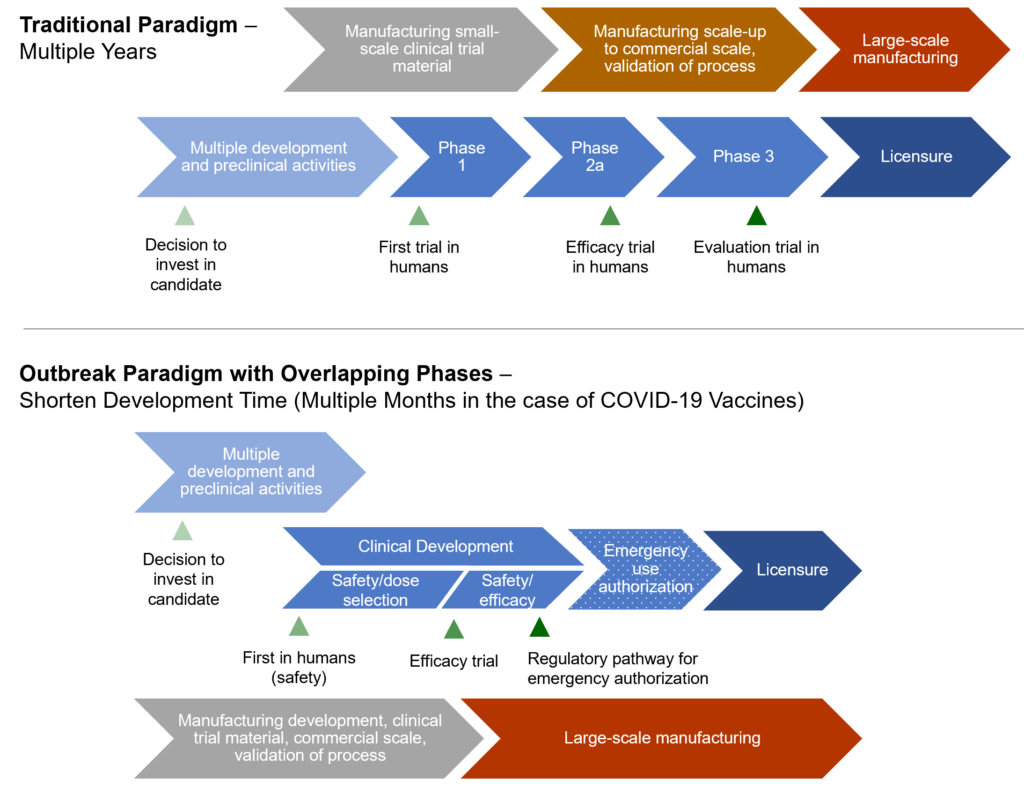

Beyond improving the rate of success, public sector funding was also key in expediting development timelines without compromising safety. Figure 1 illustrates a pandemic paradigm, whereby multiple development and manufacturing activities are run in parallel, reducing cycle times. This is only possible with support from the public sector, including governments and philanthropy, shifting some financial risk away from pharmaceutical companies to encourage development. Decreasing financial risk and increasing the probability of success feeds into a company’s decision to invest and bring a vaccine to commercial market.

Countries around the world used emergency authorization mechanisms to facilitate the rapid availability of vaccines, without compromising the quality of regulatory review. These emergency use provisions allow for unapproved products to be used to prevent serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions, when no adequate, approved, or available alternatives existed. Additionally, the World Health Organization’s Emergency Use Listing process provides additional flexibility for countries to expedite their own regulatory approval and facilitate importation of products. Understanding and utilizing these mechanisms are central to an effective response.

Despite these successes, the global community faces ongoing challenges in vaccine uptake. Overcoming these challenges are essential to fighting this pandemic and preparing for future ones.

Many countries had strong safety surveillance systems in place and as millions of people were being vaccinated in a short period of time, new systems were added. These surveillance systems are truly tested when widespread vaccination occurs. Using a variety of approaches, rare events such as an abnormal immune response associated with COVID-19 vaccine and thrombosis, small increases in cases of myocarditis and pericarditis after receiving mRNA vaccines, especially in young people, and concerns about Guillain-Barre syndrome after vaccination have been detected and evaluated. Post-marketing surveillance on efficacy is also informing vaccine effectiveness across populations (i.e., waning vaccine-induced immunity) and has led to the desire for booster doses. These surveillance systems are invaluable in the scientific consensus that the known and potential benefits of vaccination greatly outweigh the known and potential risks of COVID-19.

Vaccine hesitancy refers to a delay or refusal of vaccine, despite available supply. In the U.S., many experts have highlighted the “pandemic of the unvaccinated.” Hesitant individuals have expressed concerns about the “warp speed” of vaccine development, anchored in fear that regulation was more relaxed; the new technology in mRNA vaccines is less established; and the lack of data on long-term safety, all fueled and politicized by conspiracy theories widely propagated through social media.

Some factors shaping hesitancy are unique to COVID-19 vaccines, while others are well known with other vaccines, such as influenza, human papillomavirus, and varicella. To optimize uptake of new vaccines, understanding these barriers and exploring strategies that resonate with communities to address concerns should be considered while vaccines are in development. These must include strategies that address inequities and longstanding structural barriers to access.

A long history of vaccine nationalism, a “me-first” approach, hampers the global progress central to ending the pandemic. Early in the pandemic, countries scrambled to secure raw materials and components for vaccine production; others with manufacturing capacity (like India, which produces the most number of vaccines in the world) used all its doses to combat deadly spikes in COVID-19 cases within its own borders. This has had a devastating impact on the ability to deliver doses globally, especially to low- and middle-income countries.

To date, more than 5 billion doses have been administered across 183 countries, but countries and regions with the highest incomes are getting vaccinated more than 20 times faster than those with the lowest; these same wealthier countries are now seeking to boost immunized populations. While the ethical and public health imperatives to ensure vaccine global equity are clear, there is also a significant economic justification: the pandemic may cost the global economy $9.2 trillion if developing countries are left behind in the vaccine rollout.

COVID-19 is global problem needing global solutions. We are far from reaching vaccination levels high enough to interrupt transmission. As we plod through the pandemic, continued disease surveillance will be critical to determining who continues to acquire disease, risk factors for disease, and the role of vaccine failure versus non-vaccination in outcomes. Along the way, we are learning valuable lessons in real-time about responding to this pandemic and preparing for the next one.

The authors wish to acknowledge the thoughtful review of Charlotte Moser, Janet Weiner, Tuhina Srivastava, and Amelia Van Pelt.

If Federal Support Falls, States May Slash Home- and Community-Based Services — Pushing Vulnerable Americans Into Nursing Homes They Don’t Want or Need

Historic Coverage Loss Could Cause Over 51,000 People to Lose Their Lives Each Year, New Analysis Finds

Cited for “Breaking New Ground” in the Field of Hospital Operations

Men are Stepping Up at Home, but Caregiving Still Falls On Women and People of Color LDI Fellow Says

More Flexible Methadone Take-Home Policy Improved Patient Autonomy

Penn LDI Seminar Details How Administrative Barriers, Subsidy Rollbacks, and Work Requirements Will Block Life-Saving Care