Health Benefits of Philadelphia’s Sweetened Beverage Tax

Testimony: Delivered to Philadelphia City Council’s Committee on Labor and Civil Service

Policy

On October 4, 2023, Paula Chatterjee, MD, MPH, the LDI Director of Health Equity Research testified in front of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives Subcommittee on Health Facilities about the unprecedented market-level changes that have occurred in health care over the past decade, and the latest new hospital payment models designed to address the consequences of those changes. Her remarks focused on federal and state programs designed to to support financially stressed hospitals, particularly those in rural areas.

Views expressed by the researchers are their own and do not necessarily represent those of the University of Pennsylvania Health System (Penn Medicine) or the University of Pennsylvania.

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

Senior Fellow & Director of Health Equity Research

Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania

Before the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, Health Committee

On “Informational meeting on Hospital Consolidation and Closure.”

October 4, 2023

Hospitals in the United States have experienced unprecedented market-level changes over the past decade. My colleague, Dr. Rachel Werner MD, PhD, has provided information about the rates of consolidation, the role of private equity acquisition and the rates of closures in U.S. hospitals. My testimony will build on this foundation and focus on (1) the way in which these forces might impact hospital finances, and (2) payment models that have been proposed with either the implicit or explicit goal of reducing financial instability in hospitals.

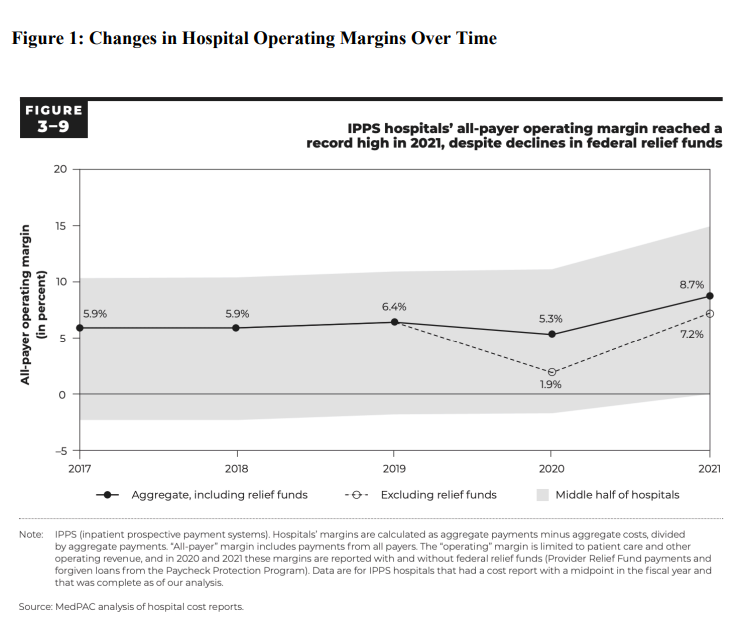

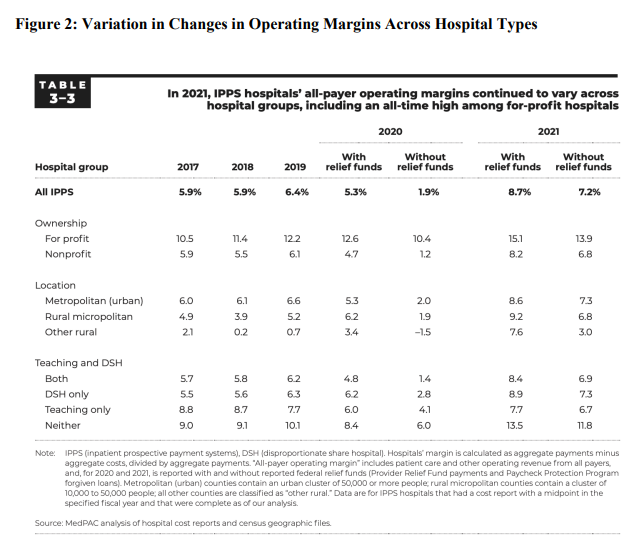

Over the same period that market-level consolidation and acquisition trends have accelerated, hospitals, on average, have fared financially well (Figure 1 below). However, there is heterogeneity across hospital types (Figure 2 below): some hospitals have experienced unprecedented profits and wealth (particularly non-profit hospitals and academic medical centers) while others have come under growing financial precarity (such as rural hospitals and safety-net hospitals).

Understanding the effects of consolidation, which most commonly manifests through hospital mergers and acquisitions, on finances is challenging due to limitations in data and reporting of hospital profits. Specifically, after a hospital becomes acquired by an entity, it becomes difficult to distinguish their financial circumstances from that of the parent entity. However, it is well established that hospital consolidation has led to higher prices with little improvement in quality of care or patient outcomes.

Private equity acquisition can be considered a subset of the broader trend of consolidation. Hospitals acquired by private equity firms typically have improvements in financial circumstances after being acquired, though at baseline, the hospitals being acquired tend to be more financially well-off relative to their local counterparts. The effects of private equity acquisition on quality of care have been mixed, suggesting improvements in certain domains (such as care for acute myocardial infarction) but not in others (such as care for heart failure).

Rates of consolidation and private equity investment have increased across all types of hospital markets, both urban and rural. Much of the existing research has focused on urban markets that are more often represented in the data used for these studies. However, the consequences of these market forces have been shown to vary across geography.

Among rural hospitals, there is some evidence that hospital mergers have been associated with improvements in quality of care. Other work suggests that hospital mergers in rural areas are associated with reductions in important clinical care service lines, such as obstetric care, surgical care, and substance use disorder care. These consequences are particularly salient for rural areas

that already suffer from access challenges and experience disproportionate burdens of disease related to maternal health and substance use.

The role of private equity acquisition in rural areas is growing: more rural areas in the United States are more likely to have hospitals that are private equity-owned. Unfortunately, given small sample sizes overall and the relatively new nature of the phenomenon, little is known about the specific effects of private equity acquisitions in these markets.

Importantly, the evidence on consolidation and private equity investment in rural markets is limited to-date and rarely causal in nature, meaning that it often does not allow for conclusions that directly connect the act of consolidation to an outcome of interest (such as changes in finances or quality).

Much attention has been brought to trends in rural hospital closures over the past several decades, which may or may not be exacerbated by trends in consolidation and private equity acquisition. A large body of qualitative evidence has suggested that rural hospital closures reduce access to care for patients in the local market. Quantitative evidence has shown that travel times for emergency and surgical care can increase after rural hospital closure.

However, whether rural hospital closures are associated with changes in patient outcomes, such as mortality, is not clear. In urban areas, hospital closures may be less likely to be associated with changes in mortality from acute conditions because there is sufficient supply of services in the local area independent of the closed facility. In rural areas, this relationship is less clear, especially given growing evidence that rural patients frequently bypass their local hospital to obtain hospital care.

Policymakers have wrestled with challenges in adequately funding hospitals while promoting efficiency, quality, and access for decades and the recent consolidation and acquisition trends have escalated the urgency.

I will discuss 4 recent payment approaches that are relevant to the challenge of ensuring hospital financial viability. Some of these approaches are specific to rural hospitals (such as Pennsylvania’s Rural Health Model and the Rural Emergency Hospital Program) while others are not.

Pennsylvania Rural Health Model & Global Budgets

Since 2019, Pennsylvania has been a site of national innovation in the space of rural health and hospital viability. The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model (PARHM) offered by the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) established global budget payments to rural hospitals to create predictable and stable cash flow, so that the hospitals would not be subject to year-to-year volume fluctuations. The goal of the demonstration was to align incentives for investments in population health while ensuring the viability of rural hospitals in Pennsylvania.

The evidence with respect to whether PAHRM has achieved its stated goals is still evolving. To date, 18 rural hospitals in Pennsylvania have elected to participate in the model. Early reports suggest that while the global budget was financially stabilizing for participating rural hospitals, the sustainability of the approach was unclear, particularly from the standpoint of the six participating payers across the state. Furthermore, distinguishing the patient-level consequences of the global budget (such as changes in access to care, chronic condition management, and population health outcomes) independent of potential effects of Covid-19 pandemic as well as associated supplementary funding for rural hospitals has proven to be a methodologic challenge.

Work on other global budget programs, such as in Maryland, has shown middling effects. After two years of participation, Maryland’s global budget program was not associated with changes in hospital or primary care use that were clearly attributable to the program. Other research, however, has reported reductions in hospital admissions and increases in emergency department use without admission.

In 2023, CMMI indicated early termination of the program due to concerns related to savings goals that may have dissuaded broader participation. Other challenges in PARHM include the fact that stabilized cash flow alone may be an insufficient financial incentive to move delivery system transformation forward for financially strapped hospitals already operating with small or negative margins. Additionally, the global budget does not represent the entire net payment revenue for hospitals, which may limit the model’s capacity to transform care delivery.

CMS’s Rural Emergency Hospital Program

In 2021, Congress established a novel provider type to offer an opportunity for critical access hospitals and certain rural hospitals to avoid closure and continue serving their communities, known as the Rural Emergency Hospital (REH) designation. Conversion to an REH allows for a hospital to continue providing emergency services, observation care, and limited outpatient services, while downgrading their inpatient care capabilities. In other words, REHs must maintain a 24-hour emergency department but will not provide inpatient care.

The goal of this program was to meet the perennial challenge of high operating costs and low inpatient occupancy rates that rural hospitals have grappled with for decades. By allowing them to downsize their inpatient care capabilities, the goal was to allow rural hospitals to avoid the high costs of operation while still maintaining access to clinical services that require timely care. Hospitals began converting into REHs in 2023, though very few have indicated their proclivity to participate. Hospitals that do participate will receive a 5% add-on to Medicare outpatient prospective payment rates and a new facility payment.

There are several outstanding challenges that remain unaddressed by the REH model, but are relevant to its implementation. Existing research has shown that REH-eligible hospitals had poorer baseline finances and provided fewer emergency, outpatient, and telehealth services than non-eligible hospitals These findings suggest that hospitals interested in participating in the REH program may have to make substantial investments at the outset to provide the services that the program is most seeking to preserve and promote in rural areas. It is not clear whether the financial resources associated with participation will be sufficient to support these types of

operational changes.

Furthermore, whether the resources allocated through the REH program can counter broader rural health challenges, such as those related to workforce shortages, remains unknown. Telemedicine may be a potential avenue to add value to the delivery of emergency care in rural emergency departments, however, the cost of implementation is a commonly reported barrier that may be limiting the extent of adoption.

CMS’s AHEAD Model

The Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) Model was announced in September 2023 by CMMI. The goal of the model is to promote investment in primary care, ensure financial stability for hospitals, and support beneficiary connection to community resources. The model “seeks to drive state and regional health care transformation and multi-payer alignment, with the goal of improving the total health of a state population and lowering costs.”

Participating states will assume responsibility for managing costs across all payers in the state, as well as ensuring that providers deliver high-quality care, improve population health, offer greater care coordination, and advance health equity. The AHEAD Model will operate over 11 years and provide participating states with funding (up to $12 million per state) as well as other tools.

Taken together, the AHEAD model seeks to combine elements from other payment programs under a single umbrella. Specifically, hospital payments will be allocated through a global budget with similar goals as those of the PARHM model. Primary care providers will also be an essential component of the model and will be closely linked to state-level efforts related to innovation in the Medicaid program.

As states can begin applying for the program in Fall 2023, it is too early to assess its consequences for hospital financial viability or patient outcomes. Important questions to consider in the coming months and years will include (1) whether the AHEAD model accounts for prior implementation challenges related to the global budget for hospitals that were revealed in both Pennsylvania and Maryland; (2) whether states have sufficient jurisdiction to motivate quality improvement to meet the targets they establish; and (3) whether incentives can be aligned between hospitals and primary care practices to ensure success of the model.

State Discretionary Funding Pools to Improve the Financial Viability of Hospitals

In recognition of the growing financial strain of certain hospitals, some states have begun to establish new pools of supplemental funding to bolster these hospitals and ensure their viability. In June 2023, the New York State Department of Health established the Hospital Vital Access Provider Assurance Program (Hospital VAPAP). The program provides “temporary (up to three years) operating assistance to financially distressed providers for the purpose of redesigning their healthcare delivery systems to promote financial sustainability. Funding is provided for operational costs associated with transformation initiatives that address financial viability, community service needs, quality of care, and health equity.” The program is open to a wide variety of hospitals, including public hospitals, critical access hospitals, and sole community hospitals, among others and is meant to target facilities with negative operating margins for the past 2 years or hospitals without assets or resources to maintain their operations.

In May 2023, California’s State Legislature passed a bill to establish the Distressed Hospital Loan Program. The goals of the program are similar to New York’s Hospital VAPAP but its scope is narrower in that it targets non-profit and publicly operated hospitals in financial distress, and is based on an interest-free loan that is payable over 72 months.

In some ways, these state-based efforts are similar to existing supplementary funding pools, such as the Disproportionate Share Hospital Payment program or the Upper Payment Limit Program. These types of supplementary funding pools come with tradeoffs. While they allow states an immense amount of flexibility in allocating funds to hospitals that they think are in need, there is significant opportunity for mistargeting of such funds. For example, recent work has shown that up to 30% of Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital payments may be mistargeted to hospitals that don’t actually need them to ensure financial viability.

While policy solutions designed to ensure hospital financial viability have typically centered on the role of payment, there are several aspects of this approach that may be worth reconsidering as well as other policy solutions outside the realm of payment that may be worthy of attention.

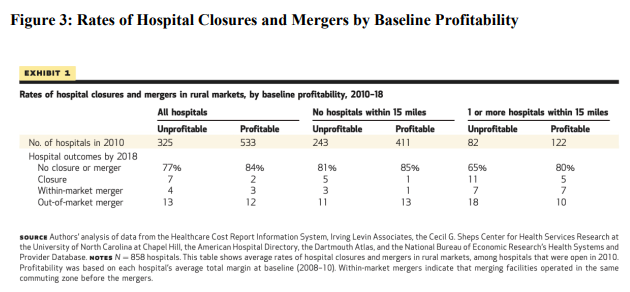

Perhaps surprisingly, hospital finances do not perfectly predict hospital closure, especially in rural markets. Recent research has found that rural markets are experiencing meaningful rates of hospital closures and mergers, yet many hospitals have survived despite persistently poor financial performance (Figure 3 below).

Instead, the closure of a rural hospital may be due to factors that are outside the realm of hospital finances and payment. It may be that bolstering rural health care may require bolstering rural communities more broadly.

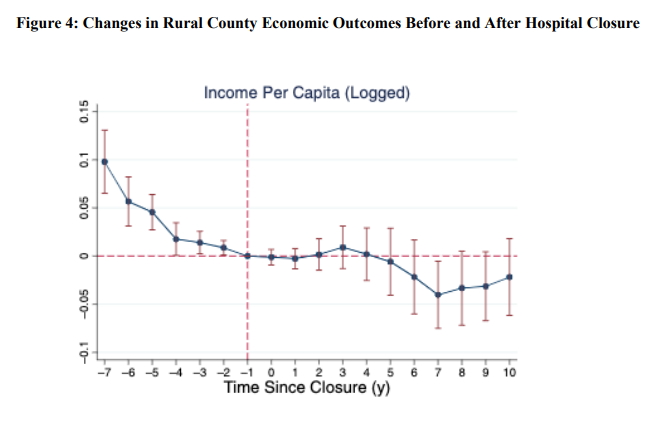

A recent study from 2020 sought to evaluate the economic consequences of rural hospital closures. Specifically, the goal of this study was to evaluate whether a county’s economic circumstances (including unemployment rates, labor force participation rates, per capita income, total jobs, health care sector jobs, disability program participation rates, percent of the population with subprime credit scores, and bankruptcies filing) worsened after a rural hospital closure.

The findings of this study suggest that while rural hospital closures were associated with reductions in health care sector employment, they were not associated with changes in any other economic measure. Instead, economic conditions were already declining in

counties with closures compared to those that did not (Figure 5 below).

The finding that economic decline precedes rural hospital closures suggests that previously hypothesized determinants of closures–such as declining occupancy rates and worsening finances–may themselves result from broader “upstream” economic drivers. These factors may include declining economic opportunity, loss of employment in other, larger, sectors of the economy, or the loss of investors and loss of other sources of community capital.

If this is the case, then efforts to reduce rural hospital closures may require a broader focus on local communities and economies in order to be successful. Existing rural economic development efforts, such as tax credits to encourage industries to enter rural markets or place-based federal investments (e.g., “Empowerment Zones”), may play an important and complementary role in reducing the risk of rural hospital closures.

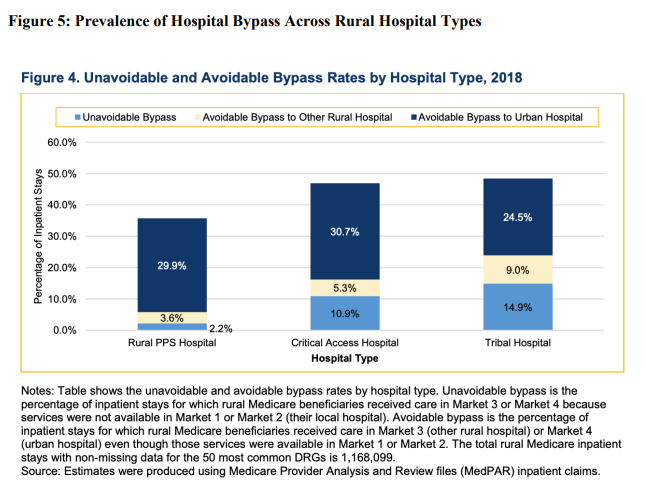

Another factor that may be contributing to rural hospitals’ financial challenges, but is often not accounted for in policy discussions, is that rural patients are increasingly bypassing local hospitals to seek care at larger hospital systems that are further away (Figure 4 below). This is true even when the needed clinical service is available at a nearby rural hospital. In 2018, CMS reported that while almost 60% of rural Medicare fee-for-service inpatient stays were at the nearest rural hospital, over 33% were at another hospital for services that could have been provided by the nearest rural hospital.

Testimony: Delivered to Philadelphia City Council’s Committee on Labor and Civil Service

Comment: Delivered to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

Comment: Submitted to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Comment: Delivered to the U.S. Department of Labor

Memo: Delivered to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Letter: Delivered to House Speaker Mike Johnson and Majority Leader John Thune