New APHA Book Warns Social Systems Are Driving Deepening Health Inequities

Penn LDI’s Antonia Villarruel and 10 Other Authors Map Social Determinants Across Multiple Racial and Ethnic Groups

News

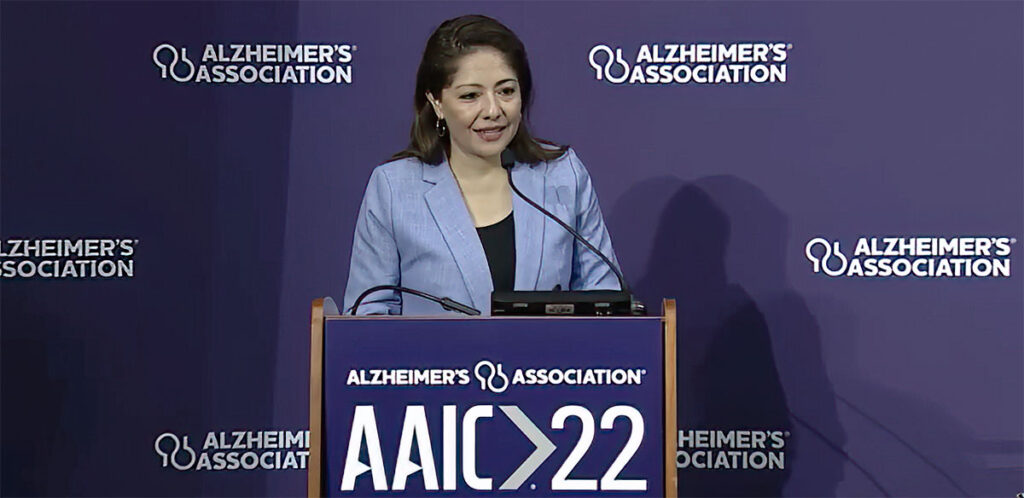

Even though they are 1.5 times more likely than non-Latino white people to develop Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, Hispanic/Latino populations are dramatically underrepresented in clinical trials testing potential treatments for those same conditions. That’s according to a presentation by LDI Senior Fellow and Penn Nursing Associate Professor Adriana Perez at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in San Diego earlier this month.

For instance, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Drug Trials Snapshots Summary Report of 2021 details how 3,300 patients were enrolled in two large clinical trials, specifically for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment or with mild dementia stage of disease. Only 3% of the selected subjects were Hispanic/Latino.

One of the primary problems is the pharmaceutical field’s insensitivity to the subtle negative messages imposed by recruitment language restrictions, said Perez, PhD, CRNP, whose research is funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging.

“Spanish-speaking older Latinos are typically excluded from scientific research because they don’t speak English and that puts them at a disadvantage when it comes to brain health equity,” said Perez.

“A recent Alzheimer’s Association survey showed that Hispanics and Latinos want to take part in research. They are willing participants, but they want to be invited,” Perez continued. “In a series of focus groups I conducted in North Philadelphia, 85% of Latino participants said they would participate in clinical trials if they were invited. But they said when they see ‘must be English proficient’ it is a message that [they’re] not invited. That’s how it is perceived — and that includes those who are bilingual or even speak English perfectly. They want to contribute to the overall goal of research. They want to benefit from the scientific advancements because they know this is a big health issue and so many themselves have a family member with Alzheimer’s disease.”

“Another issue is the lack of representation in health care providers, which is very important,” said Perez. “Meaning, I don’t have a provider that speaks my language, that understands my culture, or appreciates both the strengths I bring and the challenges I experience in everyday life. That is significant. As a nurse practitioner, every time I start a conversation with a Hispanic or Latino patient, I start in Spanish — even though most are bilingual and speak English perfectly. It is comforting. That in itself builds trust. That’s what’s missing in current clinical trial recruitment efforts for this demographic: comfort and trust.”

Current typical staffing across U.S. health care systems has Hispanic/Latino workers making up a disproportionally large part of health aides and nursing assistants. But as patients move up the treatment chain, the numbers of higher-level Latino clinicians rapidly decrease.

Perez, who graduated from nursing school two decades ago, noted: “Back then, the number of Latino nurses was about 5%. It’s hardly changed since. The growth of Spanish-speaking nurses has not tracked with the rate of growth of Latinos in the U.S. The same could be said for physicians and clinical psychologists as we continue to identify the real critical issues to address in relation to brain health equity.”

Penn LDI’s Antonia Villarruel and 10 Other Authors Map Social Determinants Across Multiple Racial and Ethnic Groups

A New Study of a Sample of Facilities Found Half Without Any Behavioral Health Staff

Physicians Were Paid About 10% Less for Visits Involving Black and Hispanic Patients, With Pediatric Gaps Reaching 15%, According to a First-of-Its-Kind LDI Analysis

New Study From LDI and MD Anderson Finds That Black and Low-Income, Dually Eligible Medicare Patients Are Among the Most Neglected in Cancer Care

Equitably Improving Care for Hospitalized Kids Who Experience Cardiac Arrest Requires Hospital-Level Changes, LDI Fellows Say

Billing Codes That Flag Food, Job, or Housing Insecurity in Medical Records are Underused for the Sickest Medicare Patients