Black and Hispanic Children Have Higher Death Rates Than White Children After In-Hospital CPR

Equitably Improving Care for Hospitalized Kids Who Experience Cardiac Arrest Requires Hospital-Level Changes, LDI Fellows Say

Blog Post

What do the increasing crime rates in major U.S. cities mean for the health of their residents? Studies have indicated neighborhood crime can harm health even among people not directly impacted by the violence. Potential long-lasting effects include increases in blood pressure and obesity, both risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

As physicians working in Philadelphia, a city with high gun violence rates, we often care for patients who have lost a friend or a loved one to gun violence. We wanted to learn more about the relationship between neighborhood violent crime rates and cardiovascular disease. Our study, recently published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, assessed trends from 2000 to 2014 in violent crime and cardiovascular death rates at the community or neighborhood level, along with several other important factors. We focused our research on Chicago, a city that, like Philadelphia, has high gun violence rates.

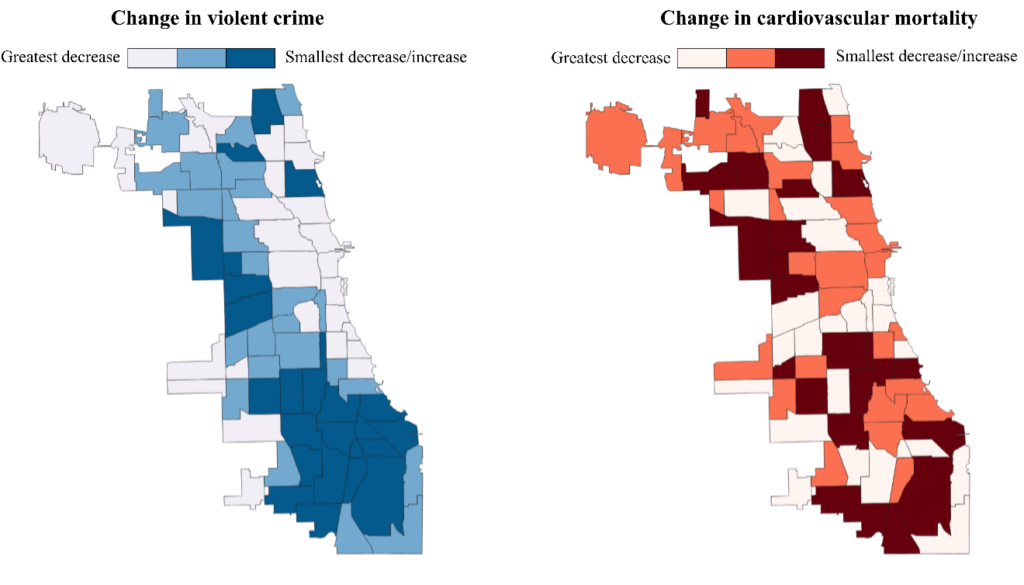

We found that overall rates of violent crime dropped throughout most neighborhoods in Chicago during the study period. However, the decline was not even across all neighborhoods (Figure 1). After accounting for trends in other measured economic-, demographic-, and health care-related factors, we found a 1% decrease in neighborhood violent crime was associated with, on average, a 0.21% decrease in cardiovascular death rates and a 0.19% decrease in coronary artery disease death rates. Differences in cardiovascular death rates between neighborhoods were worse at the end of the study period than at the beginning because crime rates did not fall in all neighborhoods.

These findings add to our understanding that where a person lives has a large impact on their health. Given that violent crime is largely concentrated in Black and other racially minoritized communities due to past and present racist policies and practices, violent crime exposure may be an especially important social determinant of health for racially and ethnically minoritized groups.

The root causes of violent crime are structural. A legacy of racist policies and practices has led to residential racial segregation, lack of economic opportunities, concentrated poverty, and targeted divestment in racially minoritized neighborhoods. This has fueled concentrated crime in communities of color. Targeted and sustained investments are needed in these neighborhoods to break the link between community disinvestment and poor health, particularly in Black neighborhoods to rectify prior injustices.

Increasing policing has not been demonstrated to reduce crime rates, but other strategies have. For example, work done by our coauthor Eugenia South demonstrated that structural repairs to the homes of low-income owners, trash clean-up, and greening of vacant lots can decrease neighborhood violent crime. These place-based environmental interventions should be prioritized on a broader scale. In addition, policies that focus on correcting past injustices, such as reparations and systemic upstream structural solutions that address inequities in housing, education, and health care for communities of color, are desperately needed.

Our study suggests that rising crime rates could leave a legacy of worsening cardiovascular health for years to come. Community partnerships are essential to further expand knowledge regarding the impact of violent crime on health and develop community-driven interventions to improve community cardiovascular health.

The study, “Association Between Community Level Violent Crime and Cardiovascular Mortality in Chicago: A Longitudinal Analysis,” was published in the Journal of the American Heart Association on July 14, 2022. Authors include Lauren A. Eberly, Howard Julien, Eugenia C. South, Atheendar Venkataramani, Ashwin S. Nathan, Emeka C. Anyawu, Elias Dayoub, Peter W. Groeneveld, and Sameed Ahmed M. Khatana.

Equitably Improving Care for Hospitalized Kids Who Experience Cardiac Arrest Requires Hospital-Level Changes, LDI Fellows Say

Billing Codes That Flag Food, Job, or Housing Insecurity in Medical Records are Underused for the Sickest Medicare Patients

Experts Say Nursing Ethics Can Help Researchers Confront Federal Disinvestment, Defend Science, and Advance Health Equity

Study Finds Major Gaps in Cardiac Care Behind Bars

Eighth Year of Program That Recruits, Mentors and Develops Junior Faculty for Health Services Research

Chart of the Day: National Study Shows White Patients More Likely Than Black Patients to Get CT and/or Ultrasounds for Abdominal Pain in the Emergency Department