New Parents Put Infants’ Health First, While Their Own Suffers

Rural Parents Had More Emergency Visits and Insurance Loss Than Urban Peers, an LDI Study Shows. Integrated Baby Visits Could Help All Parents Be Healthier

Blog Post

[Original post: Daniel Teixeira da Silva and Chethan Bachireddy; To End The HIV Epidemic, Implement Proven HIV Prevention Strategies In The Criminal Justice System, Health Affairs Blog, May 26, 2021. Copyright ©2021 Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.]

Criminal justice-involved populations are disproportionately affected by HIV. In the US, one in seven people living with HIV leaves a correctional facility each year. Marginalized populations are at increased risk of both HIV infection and incarceration, and this dual risk is amplified among communities of color.

The 2021–2025 HIV National Strategic Plan—released in January 2021 by the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—recognizes the overarching impact of the criminal justice system on the HIV epidemic and includes objectives to increase the capacity of correctional settings to diagnose and treat HIV. However, the plan overlooks the role of HIV prevention strategies within correctional settings. Two such evidence-based strategies—medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)—are the focus of this blog post.

Ending the HIV epidemic will require a comprehensive plan to prevent HIV among people most impacted by the criminal justice system. Besides the HIV National Strategic Plan—which serves as a roadmap for HHS’s cross-agency initiative to reduce new HIV infections by 90 percent by 2030—there have been some efforts to understand and address the HIV epidemic in the criminal justice system. In 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released HIV testing and discharge planning guidance for correctional settings. Subsequently, national multi-site trials—EnhanceLink and the HIV Services and Treatment Implementation in Corrections trial, funded by the Human Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, respectively—provided evidence of the feasibility of HIV testing in correctional settings and linkage to community HIV care services post-release. In 2020, the HRSA’s Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program convened an expert panel to address the needs of people living with HIV in prisons and jails, highlighting the importance of access to medication during incarceration and linkages to community providers at release. Despite these efforts, in a national survey, only 14 percent of state prisons and 30 percent of jails met CDC best practices for HIV testing, and only 19 percent of state prisons and 17 percent of jails met CDC best practices for discharge planning.

Jails and prisons are the only settings in which courts have recognized a constitutionally protected right to health care in the US. Although the criminal justice system has historically failed to deliver adequate health care, incarceration may be a platform to improve outcomes among populations most affected by the twin epidemics of incarceration and HIV. Implementing evidence-based HIV prevention strategies in correctional settings is key to preventing HIV transmission among marginalized communities.

Transgender women, Black women, Black men who have sex with men, and people who inject drugs are disproportionately impacted by the criminal justice system and identified as priority populations by the HIV National Strategic Plan. The contribution of incarceration to the HIV epidemic is most profound among low-income Black communities and is a stark example of how structural racism leads to worse health outcomes.

Although Black Americans are less likely to use drugs compared to their White counterparts, Black Americans are five times more likely to be incarcerated for a drug offense. Nearly one in five transgender women experience incarceration in their lifetime, and Black transgender women are three times more likely to be incarcerated compared to their White counterparts. While incarcerated, more than one-third of Black transgender women report being sexually assaulted.

The HIV epidemic in the US is concentrated among Black men who have sex with men, who have a lifetime risk of HIV diagnosis of one in two, compared to one in 11 among their White counterparts. Racial disparities are also stark among transgender women, with an estimated HIV prevalence of 44.2 percent among Black transgender women compared to 6.7 percent among their White counterparts. More than half of Black men who have sex with men are likely to have experienced incarceration in their lifetime, and criminal justice involvement among Black men may also contribute to HIV infection among Black cisgender women in the community setting. Incarceration disrupts social support networks and jeopardizes post-release employment and housing. A criminal record compounds the discrimination and lack of opportunity already experienced by racial, sexual, and gender minorities.

The criminal justice system has been a cornerstone of structural racism since the end of the Jim Crow era and has significantly contributed to racial inequity in HIV outcomes. The lifetime risk of HIV diagnosis among Black men is one in 20 and among Black women is one in 48, compared to one in 132 for White men and one in 880 for White women. Strengthening HIV services in correctional settings will not only improve HIV outcomes among priority populations identified by the HIV National Strategic Plan but will also advance the overarching goal of reducing health inequity.

More than one in six male inmates, and one in four female inmates, regularly use opioids prior to incarceration, and the risk of fatal overdose increases up to 129-fold among recently released prisoners. Current evidence supports providing MOUD in correctional settings; starting MOUD during incarceration can significantly reduce the risk of overdose, reduce injection-related HIV risk behaviors, and increase community treatment engagement post-release. Providing MOUD prior to release and incorporating MOUD into re-entry programs has been associated with HIV viral load suppression after re-entry, decreasing the risk of transmission among people who inject drugs and communities disproportionately impacted by incarceration.

Despite such evidence and the recommendations of federal agencies within HHS and the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, the importance of MOUD in correctional settings is missing from the HIV National Strategic Plan. This omission reinforces inequity in HIV outcomes among Black communities more likely to experience incarceration and threatens to stymie efforts to end the HIV epidemic.

In its report “Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Correctional Settings,” the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration details six areas to enhance delivery of MOUD in the criminal justice system: 1) overcoming stigma; 2) addressing threats to safety and security; 3) advancing staff knowledge and skills; 4) covering the cost of MOUD; 5) establishing MOUD providers in correctional institutions; and 6) building partnerships with community-based treatment. The report includes several examples of successful MOUD programs in the criminal justice system across county and state settings that could have informed the HIV National Strategic Plan.

HIV transmission during incarceration is more likely to occur among Black inmates and men who have sex with men, and it is also associated with prison tattooing. Despite the elevated risk of HIV transmission within jails and prisons, most inmates do not have access to methods to prevent HIV infection, such as clean needles, condoms, and, vitally, daily PrEP, which prevents up to 99 percent of HIV transmission from sex and more than 70 percent of HIV transmission from intravenous drug use. In fact, PrEP has yet to be implemented in any correctional setting. Barriers to implementing PrEP in correctional settings may include lack of knowledge among clinicians, HIV-related stigma in correctional settings, and inability of some facilities to run laboratory tests for HIV, kidney function, hepatitis B antibodies, and other indicators of disease.

Fortunately, best practices for corrections-based provision of PrEP are being developed. Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein and colleagues detail a path toward implementing PrEP for people involved in the criminal justice system that includes providing training to criminal justice-based clinicians, developing standards and protocols specific to criminal justice settings, and identifying best practices within correctional facilities. In a study evaluating PrEP knowledge among 417 inmates, only 12 percent knew about PrEP, but 25 percent were interested in initiating PrEP; thus, a clear starting point for implementing medical HIV prevention within the criminal justice system is HIV education.

If integrated into the criminal justice system, the benefits of PrEP may continue post-release. Recently released people who inject drugs are more likely to experience HIV infection. The communities that inmates return to post-release experience higher rates of HIV incidence. Black Americans face further barriers to HIV prevention and are seven times less likely to have a prescription for PrEP compared to White Americans.

Next-generation PrEP formulations, such as long-acting injectable cabotegravir, could be an important approach to providing HIV prevention during community reentry. However, people involved in the criminal justice system will not benefit from advances in PrEP if implementation of HIV prevention strategies within jails and prisons is not a policy priority.

Charting the course for ending the HIV epidemic must include county and state correctional facilities as stakeholders to successfully implement HIV prevention programs in jails and prisons. Non-medical HIV prevention strategies, such as condoms and clean needles, are supported by decades of evidence but have failed to become widely available in the criminal justice system. Without federal support and funding, medical HIV prevention strategies, such as MOUD and PrEP, will meet the same fate.

More than a decade of research has demonstrated the feasibility and efficacy of HIV prevention in correctional settings. Today, incarceration continues to play a central role in accelerating the HIV epidemic. Failing to support evidence-based HIV prevention strategies in the criminal justice system reinforces racial inequity in HIV outcomes.

The new HIV National Strategic Plan, which will define federal HIV policy through 2025, has opened the door to implementing HIV prevention services in jails and prisons by including an objective focused on increasing the capacity of correctional settings to diagnose and treat HIV. However, an additional step must now be taken to support the evidence-based implementation of PrEP and MOUD in correctional settings. Federal agencies, such as the HRSA or the CDC, should update their guidelines for HIV testing to include PrEP and provide recommendations for integrating MOUD into HIV treatment and prevention services in correctional settings. Additionally, the Biden administration and Congress could support increased funding for implementation of HIV prevention in the criminal justice system.

The challenge of implementing MOUD and PrEP across the diversity of US correctional settings is formidable and will require robust leadership, expertise, funding, and partnership at the federal, state, and local levels. The scope and suffering of the HIV epidemic demands action, and we must use every tool and strategy at our disposal.

Rural Parents Had More Emergency Visits and Insurance Loss Than Urban Peers, an LDI Study Shows. Integrated Baby Visits Could Help All Parents Be Healthier

From Anxiety and Loneliness to Obesity and Gun Deaths, a Sweeping New Study Uncovers a Devastating Decline in the Health and Well-Being of U.S. Children

Before Lawmakers Do Full Legalization, We Must Face the Reality: High-Potency Marijuana Already Harms Kids and Adults Alike

Just Discussing Punitive or Supportive Policies—Even Before They’re Enacted—Can Impact Physical and Mental Health, Especially for Marginalized Groups, LDI Fellow Says

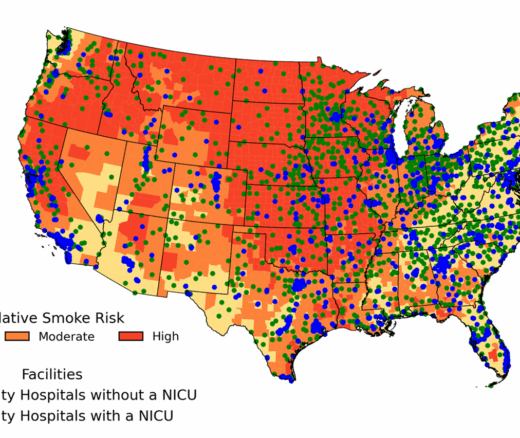

Chart of the Day: New Study Maps Maternity Care Gaps in Smoke-Prone U.S. Counties

But Many Other Factors Played a Role in Denying Loans, LDI Fellow Says

Offit and Buttenheim Criticize HHS Placebo Trial Mandate as Unethical, Misleading, and a Threat to Vaccine Confidence

A Penn LDI Virtual Seminar Explores the Latest Trends in Anchor Institution Operations