Only One in Four High-Risk Rural Births Get Appropriate Hospital Care

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

News

Establishing a context as he opened the Penn LDI October 1 virtual panel, “Building Wealth, Building Health,” LDI Senior Fellow and Perelman School of Medicine Assistant Professor George Dalembert pointed to 2019 data showing that the richest three people in the U.S. have more wealth than the poorest 50% of Americans.

Dalembert, MD, MSHP, who moderated the University of Pennsylvania session, focused on the national wealth and health disparities gap, noting that Black Americans are estimated to have 10 times less wealth than white Americans, and that 25% of Black families have zero or negative net worth.

Over the last several decades, it has been widely recognized that levels of income correlate with disparate levels of morbidity and mortality. These disparities can also drive the Catch 22 situation in which less healthy people living in poverty are less able to pursue employment and other income opportunities, thus increasing their further entrapment in poverty.

One of the interventions being explored as a potential strategy for breaking this cycle of poverty and poor health looks beyond the dense, congested bureaucracy of traditional government safety net programs to programs of guaranteed income. These interventions provide struggling families with ongoing allotments of cash with no restrictions on how they can use it.

Although enacted as a temporary pandemic-relief benefit, the Biden Administration’s American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 essentially does this with its expansion of the child tax credit of up to $3,600 for 39 million U.S. households. The apparent success of the tax credit program has greatly increased interest and discussion about how “unconditional cash” infusions could be used in other areas of social welfare and population health support.

Joining Dalembert on the panel discussion were three of the country’s top experts involved in this area of research: Amy Castro, PhD, Founding Director of Penn’s Center for Guaranteed Income Research and Co-principal Investigator of the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED); Lucy Marcil, MD, MPH, Associate Director for Economic Mobility at Boston University’s Center for the Urban Child and Healthy Family; and Ioana Marinescu, PhD, Associate Professor at Penn’s School of Social Policy and Practice, and Faculty Research Fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

In 2019, Castro’s SEED program began giving 125 families with $1,800 median monthly incomes in Stockton, California $500 a month in unconditional cash to study how it affected their income volatility, well being, employment and health. When it started, the SEED project was one of only a handful of unconditional cash research projects around the country. Today, Castro noted, there are more than 100 pilot research projects studying the effects and policy implications of the child tax credit’s unconditional cash program.

“Part of the reason cash is so effective is because it’s quick and it’s flexible,” Castro said. “Poverty creates constant needs that fluctuate by the day and by the hour. Cash is flexible, which is why it’s such a quick fix to stabilize household finances.”

“In the United States, we tend to view poverty as something like a force of nature, like it just happens,” Castro continued. “But that’s not true. Budgets are moral documents. Poverty is a policy choice. The policy we have now doesn’t have to be this way just because we’ve inherited it from those who came before us.”

“The current means-tested programs represent thresholds and policy levers and also operationalize social constructs about who we deem to be deserving and undeserving,” said Castro. “So, part of the reason that these programs are so expensive and burdensome to administer is because we say, ‘if you’re experiencing the losing end of capitalism, we don’t trust you and we want to police what you’re doing.’ The idea behind unconditional cash is the exact opposite. It is saying people know best what their needs are.”

“Nearly every member of our SEED treatment and control group met the clinical criteria for either anxiety or depression by the standardized measures used in many doctors’ offices,” Castro said. “What we saw specifically in our first year of findings was that as you calmed a household’s income volatility, you generated changes in anxiety and depression and also the amount of reported pain. The control group basically stayed the same, while the treatment group moved from ‘likely to have a mental health condition’ to ‘likely to be well.’ Literally, we did absolutely nothing else except give unconditional cash, which is incredibly exciting as a research finding.”

“In order to try to get a clearer handle on this effect,” said Marinescu, “it’s useful to look into experiments that change people’s income and wealth. For instance, studies in the U.S. have looked at Native Americans who began receiving income and unconditional income after reservation casinos were opened. The findings show important improvements in mental health in particular, and issues of drug abuse concentrated among youth in more disadvantaged communities of Native Americans.”

“The real challenge to implementing something like this on a larger scale are political feasibility and financing,” Marinescu continued. “For a long time, it was thought ‘we can’t afford it.’ But in the pandemic, we all of a sudden significantly increased cash transfers in a number of forms, including the child tax credit, which makes a huge difference to child poverty. So the issue is really about seizing the moment and striking while the iron is hot.”

Lucy Marcil noted that beyond any government effort to balance out the wealth and health gap, health systems can also play their own big role. An Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Boston University School of Medicine, Marcil is also the Executive Director and Co-Founder of StreetCred, a non-profit that partners with physicians to help patients and their families build economic stability and mobility.

The StreetCred website explains: “Families face multiple barriers to enrollment in evidence-based government support programs and financial services such as tax credits, college savings accounts, and financial coaching, including confusing applications, long lines, time scarcity, and limited transportation options. In response, StreetCred makes it easier, faster, and cheaper for families to access these services by meeting them in a trusted, frequented, untapped location: the pediatrician’s office.”

“There are many, many people, unfortunately, who are being left out of these social policies,” Marcil told the panel. “They are often the people who most need them and stand to benefit the most, both financially as well as potentially in terms of their health. They’re hard to reach. They don’t trust systems because systems have proven that they are not designed for them.”

“For the last six years,” Marcil continued, “we’ve run a tax site at Boston Medical Center aimed at increasing uptake of tax-related family benefits. Every year, about 20% of families who could be claiming their earned income tax credit do not claim it. That is reflective of national trends and is both a problem of not knowing how to claim it, and also not even knowing that it exists. This summer our clinic has done a lot of outreach work with families around the child tax credit. And despite all the attention in the media, 50% of the families we’ve been talking to are not aware of it. They don’t know if they’re eligible for it, and yet they are the very people that it’s designed for. This really highlights the need for a more grassroots approach that health care systems can be a part of—meeting people where they are and using that trust and relationship to make sure they’re empowered.”

In the final portion of the panel session, Dalembert asked the panelists: “What’s the most important thing we need to do as a country in the next 10 years to ‘get there’ in the area of child poverty?”

“There is great agreement in this panel that the answer is continuing the expanded child tax credit,” said Marinescu. “It is one of the biggest steps that could be taken to improve the situation in the US, and a policy with broad support among my economist colleagues.”

“The ramifications of growing up in poverty can be so devastating to physical health, to mental health, and to future productivity economically,” said Marcil. “No matter where in the political spectrum, and no matter what you think about poverty, you have a self-interest in making sure children in this country grow up with their basic needs met. There is clearly money in our country to make this happen. If you look at the wealth of billionaires that has been exploding during the pandemic, you can see we are making policy choices to allow them to accumulate that wealth. It doesn’t have to be this way.”

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

Former CMMI Leader Liz Fowler Cites Rigid Federal Scoring Rules and Bureaucratic Impatience for Pilot Failures

A Major European–U.S. Hospital Study Finds That Changing How Hospitals Are Organized Reduces Burnout and Turnover While Improving Care Quality

Penn LDI Senior Fellow Dominic Sisti Cites “Alarming Levels”

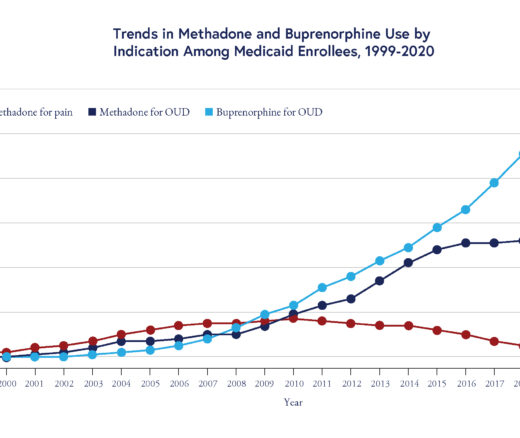

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication

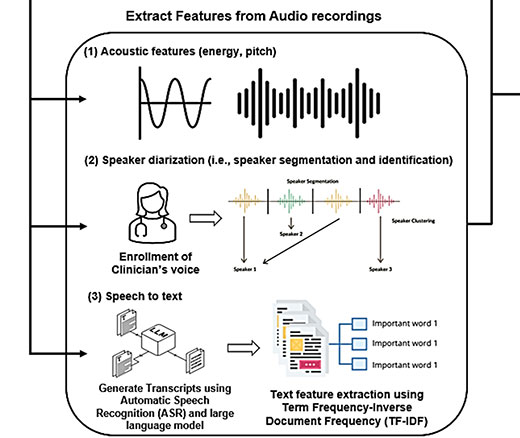

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance