Health Equity

News

Vulnerable Communities Emerge as Worst Hit by COVID-19

Penn LDI Virtual Seminar Panelists Cite Structural Racism as One of The Causes

Focused on the impact of COVID-19 in the most vulnerable communities, a University of Pennsylvania April 10 seminar sought to better understand why infections are expanding so rapidly across vulnerable neighborhoods and communities in Philadelphia and elsewhere.

Titled Meeting the Needs of Vulnerable Communities During the COVID Pandemic, it was the second “LDI Experts at Home” virtual seminar bringing together top health care research experts on a panel hosted by Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI) to explore the dynamics of coronavirus’ spread.

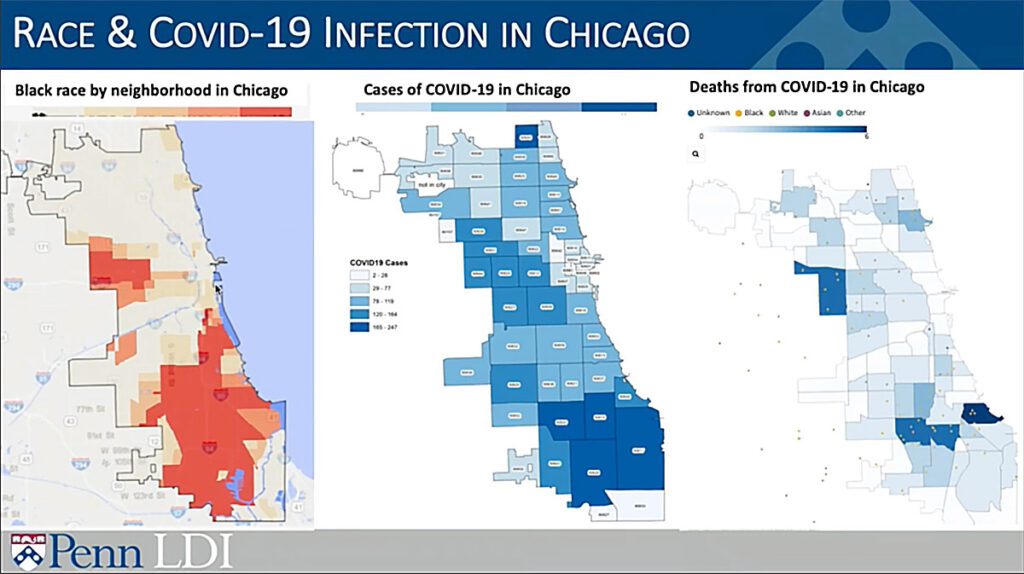

LDI Executive Director Rachel Werner, MD, PhD, opened the Bluejeans broadcast session with a series of data maps showing that rates of COVID-19 infections are highest in the African American neighborhoods of Philadelphia as well as other large cities.

15% of population, 40% of deaths

“For instance,” she said, displaying a ZIP code map of coronavirus infections in Chicago, “you can see that black residents not only have the highest rates but once infected, are more likely to die.” Another chart showed that African Americans constitute 15% of Illinois’ population but have almost 30% of all coronavirus infections and account for more than 40% of deaths from the disease.

“Today’s question,” said Werner, “is why are black Americans and other vulnerable communities disproportionately being infected and dying. There are a lot of possibilities, including higher rates of chronic conditions, limited access to medical care, and other health-related issues like poverty, environmental pollution, segregation and homelessness.”

“COVID-19,” said panelist, Perelman School of Medicine Associate Professor and LDI Senior Fellow Shreya Kangovi, MD, MSHP, “is a funhouse mirror amplifying issues that have existed for a very long time. Decades ago, we created a map of chronic disease and hospitalization rates across Philadelphia that looked exactly like these new coronavirus maps. We need to reframe this discussion because people are not dying of COVID, they’re dying of racism and economic inequality that has ultimately made them more susceptible to this disease.” Kangovi is also Executive Director of the Penn Center for Community Health Workers that is involved in a COVID community outreach.

High risk ZIP codes

“The disparities we’re seeing with COVID-19,” said panelist, Perelman School of Medicine Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, and LDI Senior Fellow, Eugenia South, MD, MSHP, “really do mirror the racial disparities we’ve seen in other health outcomes like maternal morbidity and mortality, chronic disease, and cancer rates and deaths. In some ZIP codes in west and southwest Philadelphia, which are predominantly black, up to 50% of adults have a diagnosis of hypertension that is a risk factor for coronavirus.”

“Why are black communities more likely to be located in places with high air pollution?,” South asked. “Why are our neighborhoods so segregated and why are black people so overrepresented amongst the poor? You really need to dig deeper and ask Why? Why? Why? And what you’re going to arrive at is structural racism and structural economic inequality. These are some of the root causes of the disparities we’re seeing in COVID and, more broadly, the health disparities we see.”

“For instance,” South continued, “there are more challenges to social distancing in these neighborhoods. Social distancing is a key to protecting ourselves and our families, but not everyone can do this the same. Black and poor communities have a lot more multigenerational homes with kids living with parents, grandparents and even great grandparents. So, it’s much harder to separate kids who may be asymptomatic carriers from the elderly who are at higher risk for the disease.”

40% of U.S. homeless

“You also have our essential workers,” South said, “many of whom are low-wage minorities in jobs like food services, environmental services, custodial staff, trash collectors, grocery clerks, and bus drivers. One recent estimate is that only one out of five black workers is able to stay at home right now. So, they go out to work, more likely on public transportation, and they don’t get sick leave. Then there are other populations, like the homeless. Blacks make up 40% of the country’s homeless. How do you think they’re doing in this pandemic?”

Not all that well, according to panelist Dennis Culhane, PhD, Professor of Social Policy at Penn’s School of Social Policy & Practice, LDI Senior Fellow and nationally renowned expert on homelessness in America. He explained there are 2 million people experiencing some length of homelessness each year, with 500,000 of them homeless at any one time.

There are 200,000 shelter beds throughout the country that are completely filled. However, most currently don’t provide social distancing. They are fitted out with bunk beds that, by law, must be two or three feet apart.

“In order to provide social distancing in these facilities, we estimate you’d have to roughly relocate half of the beds,” Culhane said. “Beyond that we have 300,000 more homeless people with no access to shelter facilities. Despite the $14 billion the U.S. is spending on emergency sheltering annually, we still have 300,000 homeless people with nowhere to sleep.”

Dual homeless crisis

“During the last ten years there were a couple of emerging crises within homelessness. There has been an explosion in the number of homeless and the encampments many of them live in,” said Culhane. “The second trend has been the aging of the homeless, essentially the second half of the Baby Boomer generation born after 1965. They are predominantly African American and have had very high rates of homelessness even in their 20s. They never got access to the labor market in the early 1980s and faced challenges that intersected with the crack cocaine crisis and the war on poor people related to the drug market, mass incarceration and addiction. Many now have a life expectancy of 64 years and we see in them health conditions normally associated with people 20 years older.”

“On COVID-19 testing,” Culhane said, “there has been no actual federal strategy articulated about how often testing should be done in the homeless population and how it should be coordinated. Unfortunately, that is looking pretty haphazard in different places. Last week, we had one 600-bed men’s shelter in Boston do an epidemiological study testing everyone. Two hundred people tested positive and 35% of those were asymptomatic. So, there are lots of challenges facing homeless populations in this era of coronavirus.”