Blog Post

Year One of Medicare’s MIPS Program

Partial Physician Participation Highlights Challenges in Program’s Design

The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)—Medicare’s largest pay-for-performance program—has stoked controversy since its passage in 2015, with numerous groups calling for its repeal. Because of MIPS’ administrative complexity, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) and other stakeholders have speculated that it would not incentivize physicians to improve performance, nor would its scoring distinguish high quality providers or translate to meaningful quality improvement.

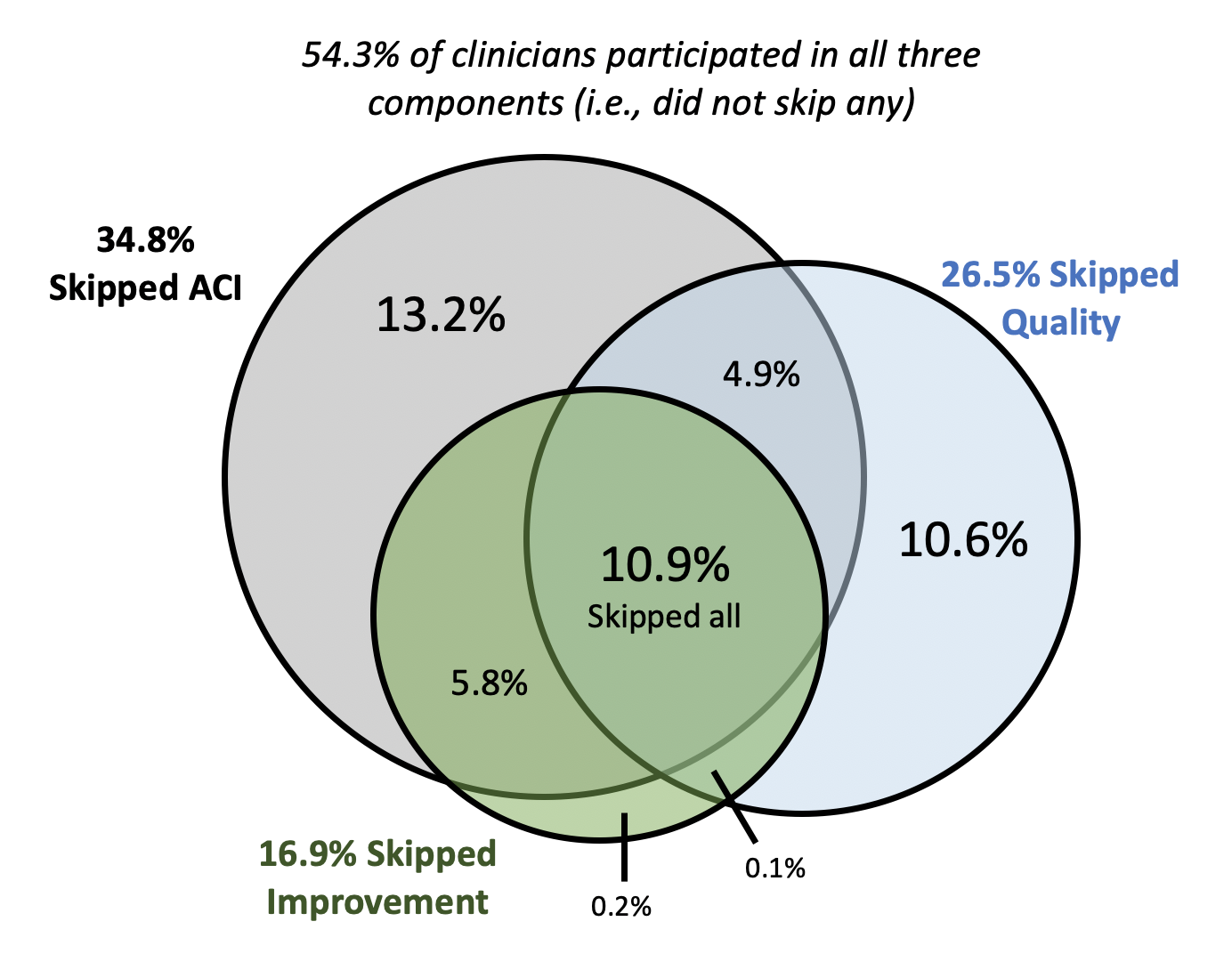

New evidence from the first year of the program suggests that these predictions were largely correct. In a recent Health Affairs study, my colleague Jordan Everson and I identify an unexpected issue with the program: providers skipping entire performance categories. Many of these providers nevertheless received positive payment adjustments, while simultaneously forgoing the meaningful quality improvement goals at the heart of MIPS and making its first year metrics unreliable for differentiating provider performance.

In 2017, provider performance in MIPS was scored across three domains: quality, improvement activities, and advancing care information (previously “meaningful use” or the Electronic Health Record Incentive Program). Providers receive a positive, neutral, or negative adjustment to their Medicare Part B compensation based on their composite score across these categories.

Using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS’) Physician Compare, we found that nearly half (46%) of providers participating in the first year of MIPS skipped one or more of the three required scoring components (Figure 1). Thus far, this phenomenon has been masked by high overall rates of providers who have avoided negative payment adjustments. However, 74% of the nearly 400,000 providers who skipped at least one performance category received positive Medicare Part B payment adjustments for their incomplete MIPS participation. Providers participating in each component also tended to score very highly, rendering the scores ill-equipped to differentiate providers based on performance. For example, 55% of providers who participated in advancing care information reported a perfect score. As a result, only 14% of the variation in a provider’s overall year one MIPS score was attributable to his or her actual performance within the three MIPS components.

Our findings confirm some early skepticism about MIPS’ low incentives and the ease with which providers can achieve a “passing” score (3 out of 100 in 2017). These factors have led to provider performance metrics that primarily indicate participation rather than performance. This has two implications. First, these metrics tell patients using Physician Compare very little about providers’ relative quality, a key goal of the original MIPS legislation. Due to low participation across performance categories, MIPS scores from year one do not reliably measure provider performance in comparison to other providers, making these scores useless to patients in evaluating potential providers.

Second, “passing” based on participation alone is unlikely to have motivated providers to undertake meaningful quality improvement. For many providers, avoiding a negative payment penalty did not require substantial changes within any of the three MIPS components. The ease with which providers could achieve a high score and the lack of incentives to improve likely led, in part, to the rates of category skipping, which also point to a more problematic trend. If providers did not, in fact, pursue incremental improvements in their technology or quality in year one, they will be behind the curve as requirements intensify. For example, the minimum score in 2020 is 45 points out of 100, with financial penalties of up to a 9% payment reduction.

Fortunately, adjustments to MIPS take place each year. In the 2021 proposed rule, CMS included considerable accommodations for providers as they respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, it remains to be seen if the last three years of intensifying MIPS requirements have reduced the amount of partial participation and encouraged more incremental improvements among providers.

CMS has yet to release data publicly for the 2018 or 2019 MIPS program years. From observing more recent performance, we will be able to discern the degree to which MIPS is driving meaningful quality improvement or merely adding to provider regulatory burden and costs to Medicare. Insight into this question will undoubtedly determine the future of MIPS and influence future regulatory approaches to provider quality programs.

The study, High Rates Of Partial Participation In The First Year Of The Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, was published in the September 2020 issue of Health Affairs. Authors include Nate C. Apathy and Jordan Everson.