Rural Health Funds May Not Reach Hardest-Hit States, Study Finds

First Rural Health Grants May Not Go to Areas With the Greatest Needs, LDI Experts Find

News

Penn Nursing Professor and LDI Senior Fellow Linda Aiken, PhD, RN, has been named the recipient of the American Nurses Association (ANA) 2026 President’s Award for her global research achievements.

According to ANA President Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, Aiken is being honored for work that has radically transformed international nursing standards.

As Founding Director of Penn Nursing’s Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research (CHOPR), Aiken has spearheaded some of the most influential global studies on the nursing workforce and patient safety. Her landmark RN4CAST study, which has been implemented in more than 30 countries across Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America, provided definitive evidence linking lower nurse-to-patient ratios and higher proportions of bachelor’s-prepared nurses to significantly lower surgical mortality rates. This research was pivotal in shaping health care policy worldwide, directly influencing the adoption of safe staffing mandates in regions as diverse as California, Wales, Ireland, and Queensland, Australia.

Beyond staffing levels, Aiken has been a driving force behind the international expansion of the Magnet Recognition Program, leading initiatives such as Magnet4Europe to redesign hospital work environments in seven European nations and helping establish nursing centers of excellence in Russia, Armenia, and the United Arab Emirates. Her work continues to serve as a global benchmark, demonstrating that strategic investments in professional nursing are essential for achieving high-quality, cost-effective health outcomes.

“Dr. Linda Aiken’s pioneering research has fundamentally reshaped nursing, informed policy, and has been used to create infrastructures that address patient safety and workforce standards,” said Antonia M. Villarruel, PhD, RN, FAAN, Dean of Penn Nursing and LDI Senior Fellow. “This ANA recognition is well deserved, and we at Penn Nursing celebrate her decades of scholarship, advocacy, and commitment to educating future nurse scholars. Her work redefined global standards for safe nurse staffing and reflects our mission to elevate nurses as leaders of innovation and equitable care.”

Aiken will receive the award on June 25, 2026, during the American Nurses Association Membership Assembly in Washington, DC. The award underscores Penn Nursing’s longstanding leadership in health outcomes research and workforce policy.

The ANA has approximately 230,000 members and represents the interests of more than 4.7 million registered nurses across the country.

First Rural Health Grants May Not Go to Areas With the Greatest Needs, LDI Experts Find

Research Brief: Cash Transfer Programs Improve Birth, Nutrition, and Early Childhood Health Outcomes

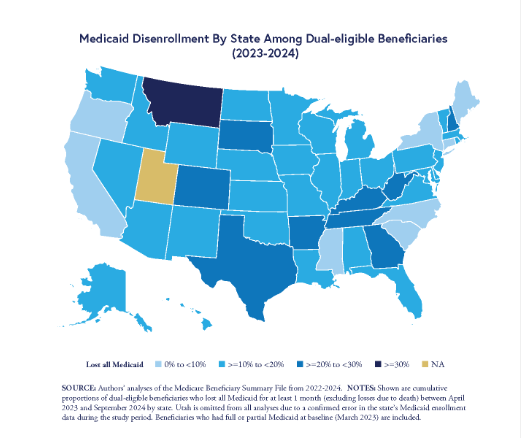

Chart of the Day: Researchers Urge Easier Renewals and Better Support To Prevent Gaps in Care

While They Wait for Medicare, People Approved for Social Security Disability Die at Higher Rates Compared to the General Public

New Evidence Undercuts Industry Warnings and Supports the Case To Restore Federal Minimum Staffing Standards

Mergers Change Where Low-Income Women Give Birth—Prompting Calls for Regulators to Weigh Effects on Vulnerable Patients and Safety-Net Systems