Black Older Adults With Cancer Are Far Less Likely to Get Any Care

New Study From LDI and MD Anderson Finds That Black and Low-Income, Dually Eligible Medicare Patients Are Among the Most Neglected in Cancer Care

Population Health

News

Can income-support programs like guaranteed income and cash transfers really improve economic security and health among low-income individuals?

That was the central question of an October 18 virtual seminar jointly sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine’s Opportunity for Health Lab (OfH) and the Leonard David Institute of Health Economics (LDI). Entitled “Boosting Health Through Economics Policy,” the session was moderated by OfH LAB Director, Atheendar Venkataramani, MD, PhD, LDI Senior Fellow and Perelman School Associate Professor.

He opened the seminar by pointing out that “one of the strongest and most enduring relationships in public health and social science is the association between income or wealth and health.” Launched in 2020, his OfH Lab has been concentrating on the broad mix of factors that create social and economic opportunities that affect health, particularly for marginalized populations.

For the last 10 years researchers have been exploring new safety net health intervention concepts like guaranteed income and cash transfers that provide unrestricted cash allotments to families over an extended period of time. And they do so in a way that, unlike welfare, gives recipients total control over how the money is spent, respecting individual choice and reducing stigma.

The programs have been controversial. Advocates argue that such regular cash payments can help stabilize families by reducing financial stress and allowing them to afford healthier food, stable housing and access to health care. Critics argue that such giveaways reduce recipients’ motivation to seek employment at the same time recipients may misuse funds for non-essential or harmful purposes.

There are many pilot research projects running such programs across the country. The seminar panelists explored the latest findings and insights coming from that work. They were: Madeline Brown, MPAP, Senior Policy Advisor in the Office of the Counselor for Racial Equity at the U.S. Department of the Treasury; Amy Beth Castro, PhD, Co-Founder and Faculty Director of the University of Pennsylvania Center for Guaranteed Income Research; William Elliott III, PhD, MSW, Professor and Director of the Joint Doctoral Program in Social Work and Social Science at the University of Michigan; and Angela Rachidi, PhD, MPA, Senior Fellow and Rowe Scholar of Poverty Studies at the American Enterprise Institute.

Treasury Department’s Brown explained, “In the last ten years, we’ve seen lots of development in traditional income safety net programs like SNAP, TANF, earned income tax credits and child tax credits. But recently, we’ve also seen movement in the areas of cash transfers and guaranteed income—since 2018 more than 100 guaranteed income pilots have emerged all over the country.”

Castro’s Penn Center for Guaranteed Income Research currently has 38 of those pilot experiments underway involving 20,000 people in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A completed one was an RCT run in Stockton, California that paid subjects $500 a month in guaranteed income for two years from February 2019 to January 2021. Published in the Journal of Urban Health in 2023, the study found that those people in the treatment arm “reported lower rates of income volatility than the control group, lower mental distress, better energy and physical functioning, greater agency to explore new opportunities related to employment and caregiving, and better ability to weather pandemic–related financial volatility.”

“One of the things that we’re seeing over and over again is that time scarcity is linked to financial scarcity,” Castro explained during the seminar. “Once people had that income volatility calmed and had more space in terms of time, they allocated it towards health behaviors in ways that we didn’t expect to see. If you think about the low-income families in this particular sample, we’re talking about an average income of $14,000 a year. Their bodies are their life insurance policy. And they know that when you are the strongest member of a financially fragile network, you are holding together the health and well-being of an entire family. They were brilliant in the ways that they reallocated the time that they gained through guaranteed income experiments, redirecting it towards things like increases in treatment compliance, resuming physical therapy, exercising more, and getting better sleep.”

Both the University of Michigan’s Elliot and Venkataramani emphasized the subtle and non-obvious benefits that can evolve from the trust and sense of connection inherent in the participation in guaranteed income and cash transfer programs.

“I talk about the idea of tangible hope,” said Elliott. “Poverty is when a poor kid is not only income poor but is also asset poor. Assets allow you to purchase a stake in your future. As someone who grew up in poverty and was homeless for periods of time, I’m really struck by how poverty is about not having a future and what that can mean to your health, your well-being, and how you think about the world. Having tangible hope for a future is more important than not being able to eat—it’s the ability to see that I can change my future through work and effort, with the help of the institutions and resources that society provides.”

Venkataramani pointed out that “the idea of tangible hope underscores the fact that a lot of public policies, and such as programs that boost income and wealth, can work through psychosocial mechanisms that shape aspirations and hopes for the future in ways that shape health behaviors and health outcomes positively. There’s actually a beautiful paper about this by economist Debraj Ray, who was writing in the international context about poverty as an aspirations trap where not having enough goods and services leads to lower aspirations that fulfill that same state.”

American Enterprise Institute’s Rachidi indicated that pilot projects finished to date show mixed results about health outcome benefits. She discussed the potential downsides of the cash programs.

“We can all agree that more income is better because it results in better health outcomes for kids,” said Rachidi. “But the question is can you design government programs that increase income in a causal way that leads to those better outcomes? The evidence is a little bit less clear about the causal relationship because there’s obviously a lot of reasons that families have low income, and just sending more income to that household doesn’t necessarily solve those issues. If those underlying issues are actually causing the bad outcomes, then those income programs will not be necessarily effective.”

“If transferring more income to households leads to less employment, those households would not benefit from all the non-financial benefits of employment, including better health,” Rachidi continued. “Another downside is the size of the payments that would need to go to households to result in meaningful improvements. They would need fairly large payments and that has a tremendous cost. We have to be aware of that and how those costs would be covered, along with any unintended consequences of doing that, like tax increases that have obvious macroeconomic implications.”

New Study From LDI and MD Anderson Finds That Black and Low-Income, Dually Eligible Medicare Patients Are Among the Most Neglected in Cancer Care

Her Transitional Care Model Shows How Nurse-Led Care Can Keep Older Adults Out of the Hospital and Change Care Worldwide

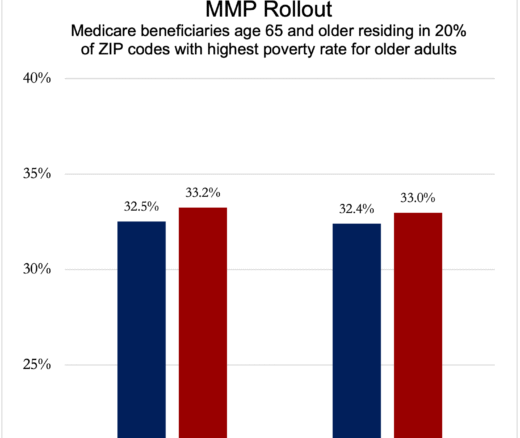

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Penn LDI Debates the Pros and Cons of Payment Reform

Direct-to-Consumer Alzheimer’s Tests Risk False Positives, Privacy Breaches, and Discrimination, LDI Fellow Warns, While Lacking Strong Accuracy and Much More

One of the Authors, Penn’s Kevin B. Johnson, Explains the Principles It Sets Out