Medicare’s Hidden Fix for High Drug Costs

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Health Care Access & Coverage | Health Equity

Blog Post

Heart disease is the nation’s leading cause of death, and yet not everyone has access to advanced, innovative cardiac care. A new study by LDI Senior Fellows Guy David, Alon Bergman, and coauthors showed that in areas with greater socioeconomic disadvantage, patients who need aortic valve replacement (AVR) tend to get fewer sophisticated procedures than patients in more privileged areas.

Conventional wisdom about new clinical technologies is that they are initially limited to large academic medical centers but then become more equitably available. This study however, suggests payment policies, regulations on procedures, and other factors may lead to an unequal distribution of new technologies, which creates inequities in access.

The team studied the use of medical technologies in different locations using 2016-2018 data for 18 states on different types of clinical procedures. They measured socioeconomic levels with a standard area deprivation index, including measures such as income, employment, and education.

The researchers compared the volumes of an established procedure, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), and two newer AVR methods: surgical (SAVR), a major open-heart procedure, and transcatheter (TAVR), a less-invasive method. Procedure volumes showed inequalities at two levels.

Overall, patients in areas of higher socioeconomic disadvantage had less access to valve replacement either by SAVR or TAVR. Unequal distribution was stronger for TAVR, the more advanced procedure, which was concentrated in areas with higher socioeconomic scores.

The most striking example was in patients 80 years and older, for whom TAVR is now recommended by national guidelines. In areas performing TAVR, volumes were, on average, 12% lower in areas with higher deprivation scores. Patients in those locations were more likely to receive a more invasive procedure with a longer recovery time even if their age suggested a less-invasive treatment might benefit them.

Additional analyses showed that another minimally invasive method, laparoscopic colectomy, was also less often performed in areas of higher deprivation. Compared to TAVR, which was introduced in 2011, laparoscopic colectomy has been available for more than 20 years. The results demonstrated that less-invasive, potentially safer medical innovations do not necessarily become more equitably available over time.

In contrast, the common, major surgery CABG was widely available overall, so access to this older invasive procedure was not unequally distributed. The results suggest that patients in areas with greater socioeconomic disadvantage tend to receive more invasive surgeries with longer recovery times and higher risks of adverse events, while one zip code away, patients with the same clinical profile might receive a potentially safer procedure.

The study adds to discussions on health equity by measuring how area socioeconomic status might affect the likelihood of getting life-saving, innovative care. It presents much-needed evidence about the availability of new medical devices and technologies.

TAVR is regulated by a Medicare payment policy, Coverage with Evidence Development, that restricts where it can be performed. Not all hospitals provide TAVR, even if they have available space, equipment, and surgeons. The study raises the possibility that the unequal availability of TAVR is reinforced by this policy. The authors note that the policy intent is patient safety but it doesn’t account for the impact on equity—that restrictions don’t affect all populations equally.

The researchers are expanding this work by measuring unequal distributions of medical technologies across multiple procedures and over time. They are creating a single measure to determine the dispersion of a medical procedure or device to see how factors such as payment policies might reduce or increase inequities in access.

The study, “Limited Access to Aortic Valve Procedures in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Areas,” was published on January 12, 2024 in the Journal of the American Heart Association. Authors include Guy David, Alon Bergman, Candace Gunnarsson, Michael Ryan, Soumya Chikermane, Christin Thompson, and Seth Clancy.

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

Pandemic-Era Medicare Flexibilities Have Proven Effective, Popular, and Safe

A 2024 Study Showing How Even Small Copays Reduce PrEP Use Fueled Media, Legal, and Advocacy Efforts As Courts Weighed a Case Threatening No-Cost Preventive Care for Millions

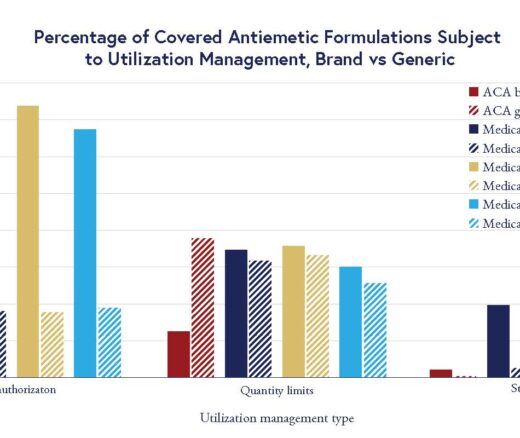

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior