Why Work Requirements Won’t Work for Medicaid

They Reduce Coverage, Not Costs, History Shows. Smarter Incentives Would Encourage the Private Sector

In Their Own Words

The following is an op-ed that first appeared in The Messenger on August 19, 2023. Because that site is now defunct, we are offering the full piece here.

A 24-year-old patient has come to see me for her annual OB-GYN visit. She proffers an array of snacks to her toddler son while she fills me in about wanting emergency contraception in case she needs it. Based on her medical history, I believe the most effective oral option would be ella, sometimes called the “morning-after pill,” which would dramatically reduce her chances of getting pregnant if she takes it within five days of having unprotected sex. I confirm her preferred pharmacy and send over a prescription.

Later that day, I learned that the patient couldn’t fill the script because her pharmacy doesn’t stock the medication. Neither do the other pharmacies near her home. She asks me if I know of a pharmacy in the city that has the contraceptive and I don’t — an answer that frustrates both of us. Yet, surely this isn’t the only instance of this happening; studies have found that many U.S. pharmacies may not have ella on hand.

Now comes Opill, the nation’s first over-the-counter contraceptive pill approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It sounds like a game-changer because anyone will be able to walk into a pharmacy and buy it without a prescription. But I wonder if people will experience the same missing-in-action frustration when Opill is set to hit the shelves in 2024. Will they go to their drugstore in an emergency only to discover that Opill isn’t there?

Perrigo, the maker of Opill, acquired ella in 2022. Like ella, Opill is considered safe by the FDA. It contains the hormone norgestrel, the same substance as in prescription-only progestin pills, which are prescribed for birth control. It could become the most effective over-the-counter contraception available.

But the pill’s usefulness will depend on whether people can afford it, which pharmacies stock it and whether it gets sold behind the counter or not. Unless the federal government intervenes, the state you live in will determine whether Opill is covered by insurance after a clinician prescribes it. Currently, only 13 states require insurance companies to cover the cost of over-the-counter methods of contraception, and in 2024, only Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York and California will require plans to cover some of these methods without a prescription. If it’s not covered by insurance, the buyers of Opill will bear the cost. With barriers in getting other emergency contraceptives, will Opill be any easier to obtain?

Here’s how it could be.

Federal policymakers and the company behind Opill could learn from issues that have plagued emergency contraception like Plan B and Ella in three ways. First, the price. Unlike Plan B or Ella, Opill requires you to take a pill daily at the same time – the cost of multiple month’s supply could add up quickly. Thus far, Perrigo has not disclosed Opill’s price, but survey data show between $10 and $20 a pack would be acceptable for most users.

Anything more would be troubling because many Americans already skip doses of all medication due to cost. Intermittent use would render Opill less effective at preventing pregnancy. Regardless of the ultimate price, the federal government should also mandate coverage for all over-the-counter contraception with or without a prescription for those on Medicaid and commercial insurance.

Second, Opill must be stocked in all retailers that operate a pharmacy. Even for people like Andrea who managed to find a healthcare provider, get to the appointment, ensure the provider understood her needs and wrote the desired prescription – medication may remain out of reach. Andrea could wait a few days so her pharmacy could order and fill her Ella prescription. This is not always the case, and for most people, Opill is time sensitive. Waiting isn’t an option for a pill you have to take daily at the same time.

Even with FDA approval for over-the-counter use, the approval has no practical value if Opill isn’t on the shelves when people need it. If Tylenol is on the shelf, Opill should be there too.

Third, Opill should not fall into the same trap as Plan B, an over- the-counter medication often kept behind the pharmacy counter. No one attempting to obtain an OTC medication safer than Tylenol should have to approach the pharmacy counter unless they have questions about its use.

Opill has been touted as a solution to increase contraception use and reduce unintended pregnancies for those with limited access to healthcare. Unfortunately, without the protective policies outlined above, Opill is unlikely to change the reality many people face when seeking contraception.

Family planning often looks more like a game of Monopoly – where a roll of the dice dictates whether you live on Park Place, with access to care, abortion, and in this case a pharmacy that stocks Opill, or on Baltic Avenue where a long history of poor policy decisions has entrenched inequities and kept effective care out of reach.

Let’s not watch this medicine go into the netherworld of our chaotic health system. FDA approval is a good first step but making it available to everyone who needs it requires a lot more work.

Alice Abernathy is an Associate Fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania and an Assistant Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

They Reduce Coverage, Not Costs, History Shows. Smarter Incentives Would Encourage the Private Sector

Research Brief: Less Than 1% of Clinical Practices Provide 80% of Outpatient Services for Dually Eligible Individuals

New Findings Highlight the Value of 12-Month Eligibility in Reducing Care Gaps and Paperwork Burdens

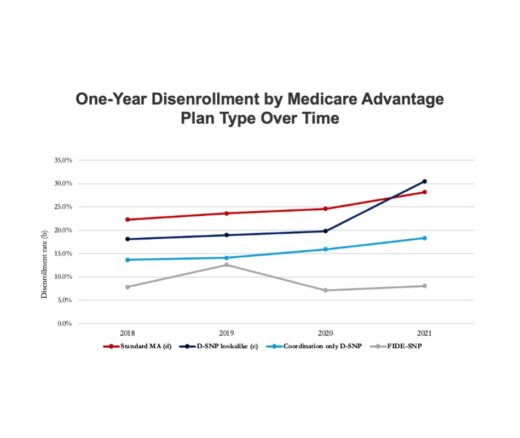

Chart of the Day: Fully Integrated D-SNPs Kept These Vulnerable Patients Enrolled, a New Study Finds

Democrats Must Go Beyond Reversing Trump-Era Cuts With a New Strategy to Streamline Coverage, Reduce Waste, and Expand Access to Medicaid

A Crisis in Maternal Care is Unfolding—and it’s Hitting Rural and Urban Communities Alike