Only One in Four High-Risk Rural Births Get Appropriate Hospital Care

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

In Their Own Words

Congress is looking to cut federal Medicaid spending by about 10%. The reasons given vary, but include deficit reduction; eliminating waste, fraud, and abuse; preserving the 2017 federal tax reductions; rolling back provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA); and general reductions in government. Some may agree with the cuts in spending; others may doubt there is evidence that they will do less harm to Medicaid beneficiaries than they will help taxpayers, but all should agree that any reductions Congress chooses should be done in the least harmful way possible. In this article, I review several frequently discussed options for such federal savings. I identify a major option that would generally shift costs and responsibility to high-income states, preserve incentives to target waste, fraud, and abuse, and make changes in Medicaid that depend on those states’ voters’ preferences about state taxes and the generosity of Medicaid.

Not all proposed approaches to federal Medicaid cuts are equal; I believe some are inferior to what I propose here. Some would directly threaten parts of Medicaid that have had wide acceptance among federal and state voters and taxpayers and are part of the fabric of our health care financing and delivery system, making them unlikely or at least challenging to change. Other options for cuts might be structured to correct longstanding shortcomings of that system. While there is no comprehensive evidence that such large and immediate cuts to federal Medicaid funding are cost-effective, I recognize that each Congress and Administration will want to shape programs to their own priorities.

Much of my review of the choices facing Congress is cautionary. Among the options for federal Medicaid cuts, I find there is much to be avoided. Even my most potentially acceptable option would need to be phased and adjusted to avoid serious adverse consequences for the most affected states. My preferred alternative is one which improves fairness across states and has the least chance for adverse impacts on beneficiaries that state voters judge to be worth less than cost savings.

My proposal involves reducing federal spending (for the sake of the federal budget) by shifting responsibility and probably cost back to the highest-income states. It is not a universal block grant approach; it would leave untouched federal subsidies to Medicaid in low-income states such as Mississippi or West Virginia but would shift costs to taxpayers in wealthier states such as Connecticut and Maryland—whose policymakers and voters could then decide whether to curtail some of their state’s more generous programs or to raise state funding to keep spending unchanged. The key idea is to reduce the federal matching rate in these high-income states below its current floor of 50%. Of course, any new level or floor will have to be politically acceptable—but this approach would both reduce federal spending and potentially reduce overly generous Medicaid spending in high-income states.

The recently passed House budget reconciliation bill includes instructions to the Energy and Commerce Committee—which has jurisdiction over Medicare and Medicaid—to find $880 billion in savings. This is widely understood to be cuts to Medicaid spending over the next 10 years or about $88 billion per year. This is almost exactly 10% of total Medicaid spending in fiscal year 2023 and just over 10% of projected federal Medicaid spending over the next decade.

Currently, Medicaid is jointly funded by federal and state governments under open-ended matching arrangements. The federal share by law must be at least 50% in all states but can be higher in states with lower average per capita income and as high as 90% in expansion states for enrollees covered under Medicaid expansion. In fiscal year 2023, states paid $280 billion of the $872 billion total, or 32%.

How the federal cuts are to be achieved is up to the House Energy and Commerce Committee to figure out, and they can consider a wide range of options. Politics aside, the relevant objective in reducing spending should, in theory, be to cut items whose (monetary) value is lower than the real resource costs saved, when possible. It would not be right to cut spending on activities whose monetary benefits to patients and taxpayers exceed their cost; that would be foolish economy.

The most discussed target for making cost-effective cuts is an old chestnut, dating back to Roman times, of cutting “waste, fraud, and abuse” (WFA). These would be any activities that either use resources for actions of no benefit or represent higher payments to supplier profits in return for nothing. It is commonplace, if true, to admit that there must be some such activities in any large government program. Still, as a policy guide, this admission is useless unless there is some feasible method to identify and end WFA. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) is widely cited as having identified “up to” $100 billion in Medicare and Medicaid WFA. What GAO actually identified as “improper payments” are not just what we think of as fraud. That measure includes claims paid with insufficient documentation, services provided in uncertified facilities or that could have been provided in a less costly setting, and tests for which there are no documented symptoms or diagnoses. These are not the things Congress can simply proscribe. GAO regularly reviews the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) efforts to work with states to improve managed care oversight, mitigate fraud risks, improve accuracy of provider enrollment, and implement audits to recover improper payments. While Congress could, and perhaps should, choose to provide greater funding for these oversight activities, I think it fair to say that there will be diminishing returns on these investments before they can eliminate all improper payments or even come close to GAO’s estimate of potential Medicaid savings. The main problem, in addition to the complexity, which hides waste in small pockets hard to hit, is that rules to eliminate WFA almost always do more harm to the innocent than they collect from the guilty. God bless a congressional committee that finds something that works.

I expect that budget cuts cannot be targeted to effectively reduce waste, fraud, and abuse in Medicaid to the maximum extent possible. Federally funded state Medicaid fraud units, at least until now, go after the shady, fly-by-night doctors, low-quality nursing homes and home care providers, and the occasional rogue provider with questionable billing practices. Savings here, if they are to be achieved, will not come from federal Medicaid budget cuts per se, but rather from continued investment in good management oversight and fraud control activities. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General estimates that state Medicaid Fraud Control Units generate three times their cost in annual savings. That suggests substantial potential for additional effort in fraud control to yield large cost reductions without harming beneficiaries or honest providers.

These units provide important checks on Medicaid providers and spending. To hold the line, it will be important to maintain federal funding for these fraud detection units, often housed within the offices of the state Attorney General, or the creation of some other vehicle (yet to be designed and proven) that can do better.

Medicaid has some natural checks that discourage overreach by providers and beneficiaries. Medicaid payment rates are not high enough for most providers to want to over-deliver services; such opportunities are greater with other payers. So far, to my knowledge, no one has identified major undiscovered targets for cuts with rigorous evidence of their lack of value. The alternative strategy of picking some suspicious spending, cutting it, and then seeing if something terrible happens is a costly method of public sector budget planning.

The goal should be to reduce federal Medicaid spending without dropping “needy” individuals from the program or denying access to high-value services. A recent New York Times article (“What Can House Republicans Cut Instead of Medicaid? Not Much,” Feb. 25, 2025) suggests that the Energy and Commerce cuts will have to come from Medicaid, and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has outlined several possible options, with cost estimates, that I can evaluate. Some might meet my criteria of protecting beneficiaries from adverse effects; others likely will not. Let’s now consider how to choose among these potential cuts so as to limit any harm to beneficiary health and promote fairness in the impact on state taxpayers.

CBO estimates that up to $893 billion in savings could be achieved over 10 years by capping federal spending across-the-board, either through overall spending limits or per-beneficiary caps. Federal policymakers would then limit federal funds to whatever fixed dollar amount they believe each state needs or deserves. These can be viewed as a variant of block grants that place the full cost of higher spending on the states. Under such block grant systems, states that spend more of their own money can no longer trigger more federal money.

The problem is that such limits are arbitrary and potentially harmful in poor states with already limited Medicaid spending. Nor do they meet the test of targeting low-value care. Limiting per capita spending could lead to the enrollment of lower-cost beneficiaries and discourage care for those with greater health needs. A difficulty with simple spending caps is knowing where to set the caps. If based on current levels of spending, they would lock in the longstanding interstate inequities where the highest income states have historically spent the most per poor person. If disconnected from current levels, they would be an arbitrary political choice (though ultimately, any policy decision will be political).

CBO estimates that $69 billion could be saved over ten years by using the same matching rate for all administrative services. Currently, many administrative services are paid at a set matching rate different from the state’s Federal Medical Assistance Percentage or FMAP. It is desirable to have higher matching to encourage activities such as fraud control and efficient administration, and modern IT systems should be able to do so at much less cost.

CBO estimates that $561 billion could be saved by reducing the matching rate for enrollees made eligible by the ACA. The higher matching rates for enrollees made eligible by Medicaid expansion under the ACA help states fill the gap between traditional Medicaid and the federally subsidized insurance marketplaces established by the ACA. To fund them is a value judgment for taxpayers, federal or state, but it seems appropriate to many. Eliminating the enhanced match would create significant financial and access problems.

CBO estimates that up to $612 billion in savings could be achieved over 10 years by limiting states’ ability to tax health care providers. Provider taxes (e.g., on hospitals and other facilities) were a gimmick used by a few states to increase their federal Medicaid funding above the prescribed matching rates. CMS’s efforts to curtail the practice met with state opposition, and the practice has grown as both Republican and Democratic administrations have turned a blind eye. Today, it is estimated that provider taxes (and other non-general-revenue sources) are used by 49 states and the District of Columbia, accounting for about 30% of the state share of Medicaid expenditures. Limiting or eliminating such practices by adjusting “hold harmless” provisions could create some federal savings and greater consistency with the program intent for shared federal-state financing.

Curtailing state use of provider taxes for Medicaid might realign federal and state cost-sharing roles toward the original matching rates and prevent states from drawing down these additional federal funds. However, the now widespread use of provider taxes means that any major curtailment would disrupt many state budgets. It is unclear how states would respond to the lower federal revenue or whether affected providers, especially hospitals and nursing homes, and their patients would suffer. Justified or not, this approach to cutting Medicaid would likely be quite unpopular across many states.

I believe that the current lower bound of 50% federal matching for the highest-income states has contributed to economic division in the country, and a further reduction could serve as a way of cutting federal spending. (This approach, incidentally, was not mentioned by The New York Times.) CBO estimates that removing the 50% floor for matching rates could produce $530 billion in federal savings. It would lead those states to be more thoughtful in their management of Medicaid and reduce the substantial — and probably unfair — variation in plan generosity and enrollment across rich and poor states. To the extent that political leaders of both parties are interested in attending to the root causes of our national divisions and waste, this kind of Medicaid financing reform should be one item included in the discussion.

Lowering the matching rate floor would not specifically target fraud and abuse but rather can be seen as a way to transfer costs to states most able to pick up the funding and most incentivized to detect and deal with WFA. Currently, if Colorado spots and ends a costly, wasteful practice, it only keeps half the savings; it might be more vigilant if it could keep the full amount. If federal cost savings are to be used to extend the 2017 tax cuts, the benefits of federal cuts may primarily accrue to corporations and high-income individuals.

Lowering the 50% floor would reduce federal matching for California, Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Washington, and Wyoming. These states could, if they wished, decide whether to continue benefits at the same level, paying a somewhat greater share of state funds. They may logically look to their larger shares of corporations and high-income individuals as the places to increase state taxes to make up the difference. Massachusetts may suggest a likely response, passing a Fair Share Amendment in 2022, which imposes a 4% tax surcharge on annual income above $1 million. The Fair Share tax is generating billions annually for transportation and education. Massachusetts and other high-income states might use such “millionaire’s taxes” to compensate for reduced Medicaid matching. Even if they do not, the resulting cuts would fall on states that tend to have broader Medicaid eligibility and higher Medicaid benefits. So, reductions in Medicaid spending in those states could leave their providers and beneficiaries better off than those in some other states. Other high-income states could look to similar financing changes.

Consider the ten states that would be affected by lowering the 50% floor. Table 1 shows three key measures: (1) Total Medicaid Spending per poor person, which represents the level of Medicaid benefits provided to the poor population (2) State Medicaid spending as a percentage of aggregate taxpayer-adjusted gross income, which represents the nonfederal burden of Medicaid on state taxpayers, and (3) State Medicaid spending as a percentage of federal income taxes paid. All but one of these states provide Medicaid benefits at a higher level than the national average. So, each of these could reduce benefits while keeping benefits above a national standard of support. Four of these states have a Medicaid tax burden below the national average. They could increase state taxes to offset the lower matching without burdening their taxpayers more than the national average. Five of these states spend less than the national average on Medicaid as a percentage of their federal income taxes paid, suggesting that their state tax burden for Medicaid is a lower share of what they pay in federal taxes than in other states. We do not know how these states will respond in the short or long run, but they at least all have options that would not disadvantage their taxpayers or poor population relative to national standards. That is, high-benefit states could reduce benefits, and low-tax states could increase taxes. My prior work has also shown that different states display different preferences for tax-financed care for their poor; Southern states in the 1980s were more reluctant. That effect seems mitigated somewhat, but it is still surely possible that other more liberal states with different voter preferences may prefer to sustain high benefits even if the cost bites into other state spending or private consumption. Ultimately, democratic choice is the ultimate arbiter of public sector decisions, not the opinions of experts or medical professionals.

| Total Medicaid spending per state resident in poverty | State share of Medicaid spending as a % of adjusted gross income | State share of Medicaid spending as % of federal income taxes paid | |

| United States | $23,399 | 1.8% | 12% |

| Washington | $44,373 | 2.2% | 14% |

| New York | $41,661 | 3.4% | 20% |

| Massachusetts | $38,754 | 2.2% | 13% |

| Connecticut | $32,786 | 1.8% | 10% |

| Maryland | $32,421 | 2.1% | 14% |

| New Jersey | $29,196 | 1.6% | 10% |

| California | $27,442 | 2.1% | 13% |

| Colorado | $27,398 | 1.6% | 10% |

| New Hampshire | $25,092 | 1.2% | 8% |

| Wyoming | $14,810 | 1.0% | 6% |

First, I recommend revamping the federal-state Medicaid financing system to better reflect state needs and ability to pay. At the same time, I would encourage voters and politicians in high-income states to let go of Medicaid financing provisions that have long enabled them to offer more generous benefits supported by taxpayers in other states. These states may be best positioned to maintain support for low-income populations without overburdening taxpayers. Another area to consider is limiting the use of hold harmless provisions for provider taxes. This approach would direct cuts toward states that have gamed the current system to increase their federal funding; however if not implemented gradually with time for states to adapt, this change could seriously affect some Medicaid providers and impair access for Medicaid beneficiaries. Some combination of reducing the 50% floor and lowering the provider tax hold-harmless threshold could be considered.

While the cuts in areas I suggest do not seem likely to impair the fundamental purposes of the Medicaid program, they may nonetheless impose significant short-term budgetary challenges on the most affected high-income states and their providers who have come to depend on more generous federal Medicaid funding. States and providers will need to plan for additional state taxes or cuts in payment rates, eligibility, or benefits. Congress should consider phasing in any such changes to allow time for states and providers to adjust.

Whether rich states would choose to make up for the lost federal matching fully is unknown at this point.

Medicaid cuts of the magnitude currently being considered by Congress should be implemented by reducing federal subsidies to many of the higher-income states. Those states may or may not significantly reduce the health care benefits that their lower-income residents use. Congress, and especially these states, will have to weigh the tradeoffs. Do the savings in the federal deficit or in federal taxes outweigh the increased costs in state taxes and the value of lost coverage for lower-income populations? As a federal-state program, Medicaid has always required balancing the interests of federal and state taxpayers. It has always had to contend in a federal system with widely varying needs, preferences, and resources among the states. Today, as in the past, the program will be shaped by how those issues are resolved.

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

Former CMMI Leader Liz Fowler Cites Rigid Federal Scoring Rules and Bureaucratic Impatience for Pilot Failures

A Major European–U.S. Hospital Study Finds That Changing How Hospitals Are Organized Reduces Burnout and Turnover While Improving Care Quality

Penn LDI Senior Fellow Dominic Sisti Cites “Alarming Levels”

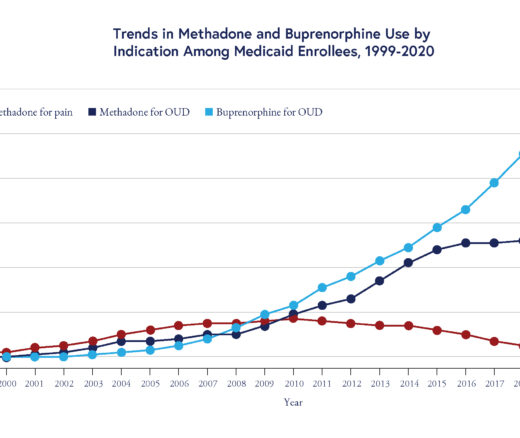

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication

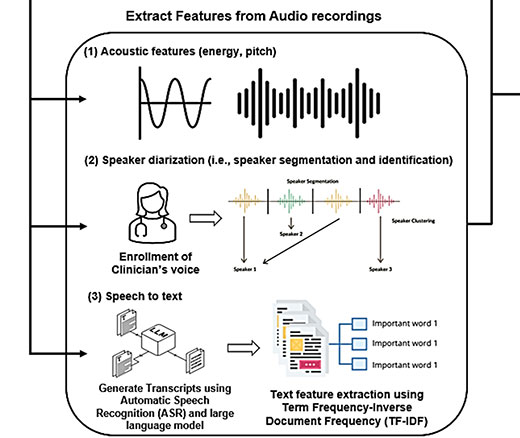

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance