Experts: Medicaid Cuts Could Prove Fatal for Thousands

Historic Coverage Loss Could Cause Over 51,000 People to Lose Their Lives Each Year, New Analysis Finds

Blog Post

Childhood hunger and food insecurity have risen dramatically in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent economic recession. Since March 2020, 1 in every 4 children has experienced household food insecurity, where their access to adequate nutrition was limited by their family’s financial resources.

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, or WIC, provides nutritional support and nutrition education to food insecure children and families in poverty. WIC has proven health benefits for participating women and children, including lower rates of preterm birth, decreased food insecurity, and improved nutrition. However, prior to the pandemic, only about half of all eligible families received WIC benefits. One reason for these low participation rates are the administrative burdens that families face when enrolling in WIC and when accessing and redeeming WIC benefits.

In a recent study in JAMA, we examined one way in which these burdens may have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participating families receive electronic benefits transfer (EBT) debit cards, which they can use to purchase approved food and beverage products from vendors who accept WIC benefits. Nine “offline EBT” states (Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah, Texas, and Wyoming) currently require WIC beneficiaries to present these cards in-person at their local WIC office every 3-4 months to reload their benefits. In all other states, WIC EBT cards are automatically reloaded online (remotely) each month, and beneficiaries do not have to travel to WIC clinics in-person during the pandemic.

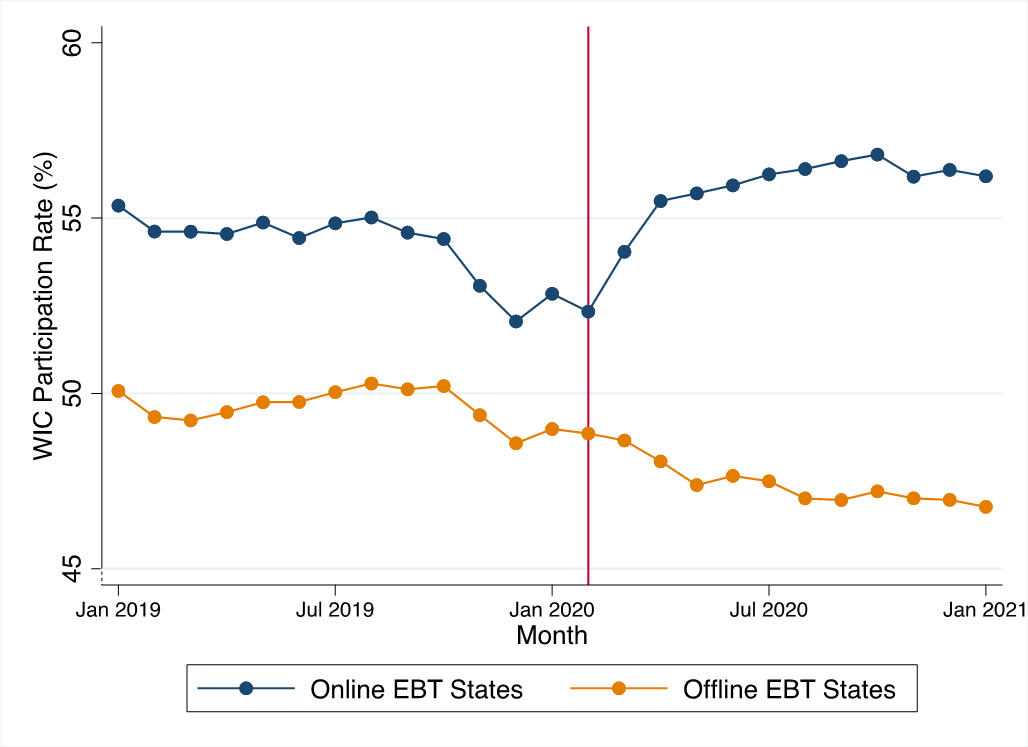

Did offline EBT reloading limit access to benefits when they were needed most, because eligible families chose not to risk in-person contact during the pandemic? To estimate this effect, we compared WIC participation before and during the pandemic in online and offline EBT states. Prior to the pandemic, WIC participation declined in both online and offline states; during the pandemic, however, WIC participation increased sharply in online EBT states while it continued to decline in offline EBT states (Figure 1).

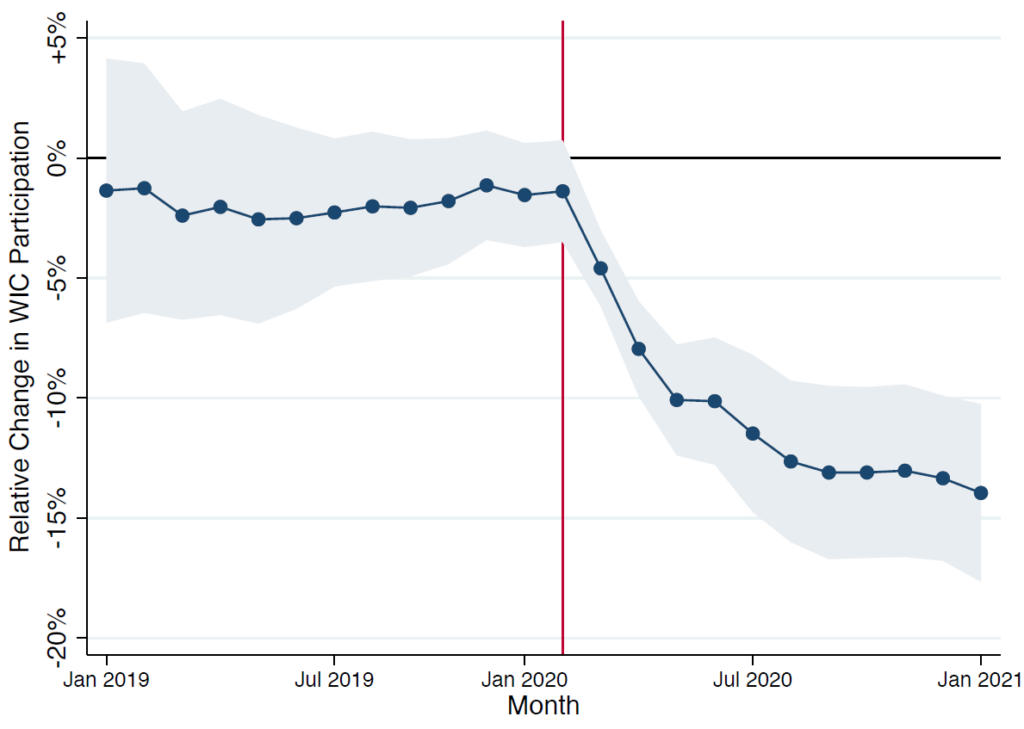

Over the first nine months of the pandemic, states with offline EBT experienced a 9.3% decrease in participation, relative to online EBT states. As of January 2021, we estimate that WIC participation was 14% lower in offline states, relative to online states (Figure 2). This corresponds to an estimated 160,000 fewer beneficiaries in these nine states.

Our findings show that administrative barriers to accessing government benefit programs can significantly reduce participation. These results have important policy implications for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and for administrators of WIC and other government benefit programs.

Collectively, these steps could help ensure that the WIC program, which is one of our most effective tools against early childhood hunger in the U.S., can continue to reach the children and families who need it most.

The study, Association of Remote vs In-Person Benefit Delivery With WIC Participation During the COVID-19 Pandemic, was published in JAMA on August 20, 2021. Authors include Aditi Vasan, Chén C. Kenyon, Christina A. Roberto, Alexander G. Fiks, and Atheendar S. Venkataramani.

Historic Coverage Loss Could Cause Over 51,000 People to Lose Their Lives Each Year, New Analysis Finds

Cited for “Breaking New Ground” in the Field of Hospital Operations

Men are Stepping Up at Home, but Caregiving Still Falls On Women and People of Color LDI Fellow Says

More Flexible Methadone Take-Home Policy Improved Patient Autonomy

Penn LDI Seminar Details How Administrative Barriers, Subsidy Rollbacks, and Work Requirements Will Block Life-Saving Care

His data-driven initiatives risk violating consent, spreading stigma, and reviving vaccine misinformation, LDI Fellow writes.