HIV is Not a Crime: The Case for Ending HIV Criminalization

Outdated Laws Target Black and Queer Lives in Over 30 States, Fueling a Deadly Disease

News

THRIVE, an innovative post-discharge support system for low-income Medicaid patients that has succeeded at the University of Pennsylvania Presbyterian hospital in West Philadelphia has received a $300,000 grant from the Rita and Alex Hillman Foundation to expand and further develop its operations at Penn’s Pennsylvania Hospital in Center City Philadelphia.

Evolved out of a 2018 pilot research grant from the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI), assistance from the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation (CHCI), and support from the Penn School of Nursing Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research (CHOPR), THRIVE is a richly resourced transition program that provides extended clinician-managed home care and social services connections for safety net Medicaid patients following their discharge from inpatient hospital care.

Margo Brooks Carthon, PhD, RN, principal investigator of the original research project, Penn Nursing School Associate Professor, and LDI Senior Fellow, now leads THRIVE. She is also the Nursing School’s Endowed Term Chair of Gerontological Research and Associate Director of CHOPR.

Established in 1966, the New York City-based Rita and Alex Hillman Foundation is a philanthropic organization focused on nursing innovation in health care education, research, and implementation. The Hillman Catalyst Award that Carthon won supports research focused on the complex health needs of communities “that experience discrimination, oppression, and indifference.”

“We’re excited to see this recognition, funding, and growth of THRIVE,” said LDI Senior Fellow and Penn Medicine Chief Innovation Officer Roy Rosin, MBA. “It was so great to work with Margo as an Innovation Fellow early on and see her passion and determination to help vulnerable populations. She got deeply embedded to identify the needs and see what others were missing. The impact of both her insights and drive are increasingly clear as THRIVE continues to evolve and improve care for patients.”

In the patient population targeted by THRIVE, the previous hospital readmission rate within 30-days was 28%. For its first 800 patients, the THRIVE program decreased that by 60% to 11%. And the overall wellbeing of the patients has been amplified in other ways. They all get a home care program. Their hospital physician remains in close contact with their home care nurse for a month after discharge. Post-discharge care is reviewed weekly by a case management committee that includes nurses, physicians, and social workers. And patients are systematically assessed for, and connected to, local social service providers for things as essential as food, housing, transportation, and behavioral health care.

Overall, THRIVE is a system designed to directly address the social determinants of health that play such a large role in patients’ overall health and health outcome prospects following an in-patient episode of care. It is driven by an electronic health records algorithm that identifies potential THRIVE participants among the latest hospital admissions and coherently follows them through their discharge transition and into home care.

Since the program was launched in early 2019, nearly 50 Penn Presbyterian hospitalist physicians have volunteered to extend their services to directly consult with home-care nurses managing THRIVE patients during the first 30 days after discharge—a major change from traditional practices.

When the initial LDI Working Group headed by Brooks Carthon began the research project, the data showed them that about only one in five discharged Medicaid hospital patients went into well-structured, clinician-managed home care during their first month of recovery. The majority just went home from the hospital to figure out their complicated and resource-challenged situations on their own.

“Patients are admitted to the hospital because they need 24/7 care,” said Brooks Carthon. “If you’re insured by Medicaid and you’re discharged, you go from 24/7 care to nearly nothing.”

She described a patient researchers encountered early in the process of focusing the first phase of their Working Group’s project. He was a young Medicaid recipient who had been discharged after a bowel resection and was stuck in his home and disoriented by his condition. He was throwing away his colostomy bags rather than cleaning them, because he found the task so awful. But it meant his bags would quickly run out because his insurance wouldn’t cover enough bags for a full month. When asked where he would get new bags, he said he would just go to the emergency room, but was barely able to walk to a local grocery store. He had no primary care physician because, he said, he had never been sick before. His diet consisted primarily of eggs and spaghetti. Getting to a crucial follow-up appointment with his surgeon was a challenge because it was a 90-minute trip with multiple SEPTA transfers. His all-consuming goal was to get back to work.

“This patient’s case had a pivotal impact on me and even more so on the young, white, hospital-based nurse who did a lot of our team’s contextual inquiry,” said Brooks Carthon. “She said she never envisioned what it was like for people to go home and try to navigate after surgery or what their living conditions could be like. It also helped our team to see how disconnected health care can be from real human experience and became the reason I wanted this project to focus on post-discharge home care and patient social needs. And it made me think of all the times I’d heard health care providers talk about patients like this as ‘frequent fliers, or super utilizers, or train wrecks,’ in a way that is just open bias. I know how that can affect the quality of care you get when providers are kind of apathetic to whether you come back or not, or when the clinical working environment simply doesn’t provide resources or time to think about this kinds of patient issues.”

“There are so many people like this patient, hospitalized in our health care system that are transitioned to care in ways that don’t necessarily set them up for success or for healing and recovery,” Brooks Carthon continued. “We asked nurses from different units, ‘What do you do for people like this bowel resection patient?’ and we would get five different responses. Some say ‘Well, I’ll call social work’ or ‘I’ll call community health workers.’ Others say, ‘I try not to ask patients a lot about these things because I don’t have solutions and I don’t want to open a Pandora’s box.'”

“Still others,” said Brooks Carthon, “say the problem is that there aren’t enough community social support resources and ask, ‘is this really a problem about health care delivery or about community resources?’ This all creates a kind of apathetic detachment and a sense of ‘this problem is too big or too cumbersome to address and there’s no silver bullet to fix it.'”

“We now know from THRIVE experience here in Philadelphia that there is not a lack of community social services and resources,” Brooks Carthon continued. “They really abound. Managing the use of them in a hospital transition program like ours is about making connections in the community and ensuring your team has real community representation. The people who are saying ‘there aren’t enough social services’ are people who lack community connections and don’t know what’s available.”

• • •

The daughter of a schoolteacher and a pastor, Brooks Carthon grew up in Baltimore and Tinton Falls New Jersey and was influenced in her young career dreams by the nurses in her church. In 1995 she earned a Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (N.C. A&T), the country’s largest Historically Black College or University (HBCU). She remembers it as a time when she had no thoughts about disparities in health care and a general feeling that the health issues her family members and friends encountered were pretty much the same as everyone else.

“Most of the people I trained with at A&T looked like me. It was like when you’re a fish in a fishbowl, you don’t know you’re wet. I didn’t really think much about race and people dealing with chronic health needs or how white folks lived their lives or received their health care differently,” she said. “Twenty-five years ago, in nursing school, that just wasn’t how we were taught.”

In 1996, Brooks Carthon entered the University of Pittsburgh to pursue her Master of Science in Nursing degree. Her clinical assignment during those studies was at a community health care center in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, a predominantly African American community that was one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. The experience was the pivot around which her career vision turned. She was determined to become to a health disparities researcher.

“Being a nurse in the Hill District kind of shook me,” Brooks Carthon said. “Being a nurse practitioner there enabled me to see up close how other people didn’t experience health care the way I had been seeing it. Every day there, I was looking at how the health care system worked against people who didn’t have access to high quality care, and it fully convinced me that I wanted to do work related to minority care.”

Brooks Carthon arrived at Penn School of Nursing in 2004 to begin her PhD studies and went on to become an Assistant Professor in 2010 and an Associate Professor in 2017.

Her 2009 doctoral dissertation reflected her deep involvement with Penn Nursing’s Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing. Entitled “No Place for the Dying: A Tale of Urban Health Work in Philadelphia’s Black Belt, 1900-1930,” the dissertation focused on the tuberculosis epidemic that ravaged the city in that 30-year period. It was an in-depth analysis of how severe disparities in social resources, health care access, and local government attention resulted in dramatically higher tubercular mortality levels among the city’s African American residents.

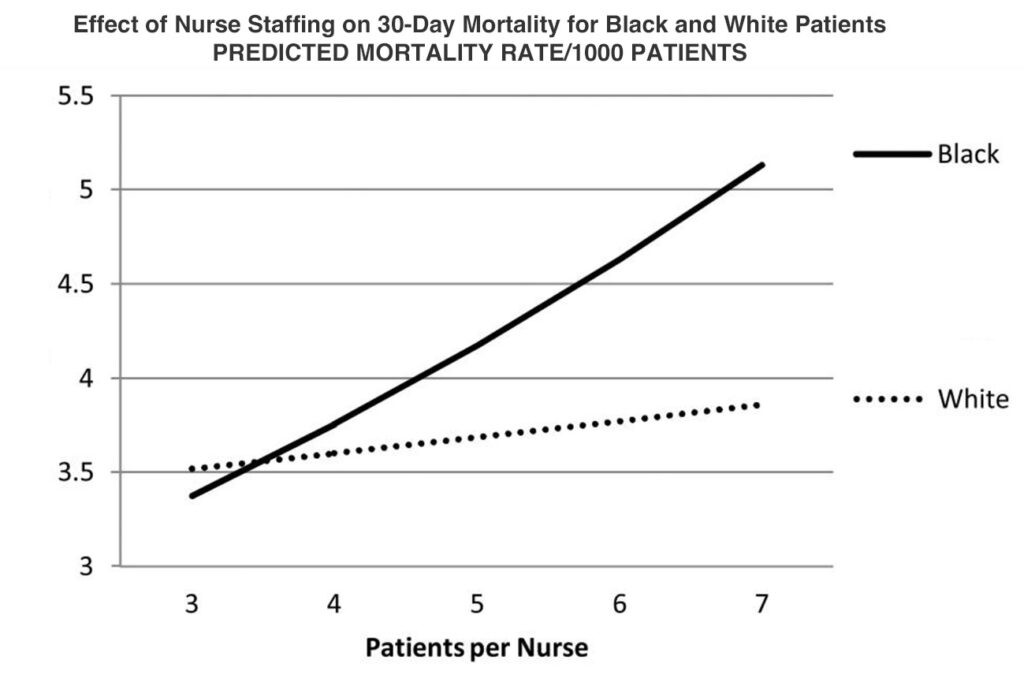

She also became heavily involved in the Nursing School’s CHOPR where research teams headed by LDI Senior Fellow Linda Aiken, PhD, RN, were conducting both domestic and international studies of how hospitals’ clinical working conditions and nurse-to-patient staffing levels affected the quality of patient care. For instance, a landmark Aiken study documented that 30-day mortality rates after common surgical procedures increased by 7% for each additional patient added to a nurse’s workload beyond a safe nurse-to-patient ratio.

Inspired by this CHOPR work, Brooks Carthon focused her own research on drilling down further to isolate and measure how suboptimal nurse working conditions and overloaded nurse-to-patient ratios impacted the outcomes for post-surgical minority patients.

The first published work in what became a 10-year string of studies on this topic came out in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society in 2012. It found that “A significant interaction was found between race and nurse staffing for 30-day mortality, such that Blacks experienced higher odds of death.” It was one of the first papers showing that relationship.

“When I came to CHOPR,” Brooks Carthon said, “I was curious about the ways that nurses may influence the outcomes of those who are vulnerable or at risk for disparate outcomes. Over the last decade, my work had repeatedly shown that Black patients — and older Black patients in particular — are really vulnerable to these fluctuations in nurse staffing. In general, and in aggregate, patients are more likely to suffer higher mortality when nurses are caring for more patients. That risk is three times worse for older Black patients who come into the hospital with higher chronic conditions and worse severity of illness.”

About five years into this 10-year research agenda documenting a racial disparity that had gone unnoticed and unaddressed throughout the era of modern medicine, Brooks Carthon had another career epiphany. Looking back on her 15-year career as a nurse scientist, she recounted how she came to see that it was one thing for a researcher to describe and document racial disparities, but quite another to address and mitigate those inequities that have resulted in such extraordinary and unnecessary levels of unabated illness and mortality across marginalized populations. She realized that she wanted to change disparities rather than just describe them.

In 2017, that determination led her to both the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation as well as to LDI for the pilot grant enabling her to form a Working Group focused on developing interventions to improve care of Medicaid patients transitioning out of the hospital. That became the THRIVE program.

She noted that her journey hasn’t always been easy in the way that it often mirrored the very structural racism that her research was aimed at exposing.

“Looking back, it’s interesting to think about the scholarship that’s now occurring related to structural racism,” said Brooks Carthon. “Ten or 15 years ago, it was very different and could be discouraging. I felt isolated back then because it was a research topic not in vogue even though I started my doctoral education shortly after the Institute of Medicine’s “Unequal Treatment: What Health Care System Administrators Need to Know about Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare” came out. Some of us saw that this was going to create a research space for disparities, and we were coming to it early.”

“But still, I did not describe my work back then by saying that I was interested in structural racism because that was a clear way not to be funded. No one was funding structural racism, especially not racism in nursing. It’s just been in the last three years that we’ve seen people really come to grips with what has been there for so many decades. So, I am grateful because I feel like I’ve found a space where I have been able to find my voice and thrive as a researcher in this field.”

Outdated Laws Target Black and Queer Lives in Over 30 States, Fueling a Deadly Disease

Selected for Current and Future Research in the Science of Amputee Care

Penn LDI Seminar Details How Administrative Barriers, Subsidy Rollbacks, and Work Requirements Will Block Life-Saving Care

Top Experts Warn of Devastating Impact on Community Safety Efforts

A Gathering of a Health Services Research Community Currently Under Siege

1,000+ Detail the Latest Health Services Research Findings and Insights