Acupuncture Could Fix America’s Chronic Pain Crisis–So Why Can’t Patients Get It?

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

Brief

Community health centers (CHCs) face substantial obstacles to participation in value-based payment models, in which payers reward performance on health outcomes. Further, these models rarely measure and reward efforts toward population health equity, a central CHC goal and outcome. In this issue brief, we recommend ways to promote and enhance CHC participation in value-based payment, and strategies to align these efforts with health equity goals. We base these recommendations on a series of focus groups and conversations with frontline CHC leaders, payers, and payment policy experts.

Community health centers (CHCs) are a key component of the health care safety net, providing essential services to low-income, uninsured, and underinsured patients.1 Because they provide care to patients regardless of their ability to pay, CHCs face substantial financial challenges in serving patients who are at a disproportionate risk for poor health outcomes due to social determinants of health.

Over the past few decades, value-based payment (VBP) has emerged as a strategy to improve quality and contain costs. It is useful to think of VBP as a payment approach that promotes high-value (or value-based) care, in which care is designed (or redesigned) to focus on the overall health of a patient along with their values and goals. One of the hallmarks of VBP is holding providers accountable for quality by tracking and rewarding measurable outcomes.

Clinical quality measures often used in VBP may not fully capture the value of care at CHCs, given the scope of services they provide. Further, part of the “value” that CHCs provide stems from their ability to address the social determinants of health, provide services that enable care, and promote health equity. These activities are rarely included in quality metrics and rarely rewarded in VBP programs.

CHCs have many of the same pressures as other health care organizations to improve quality, reduce cost growth, and advance population health. However, CHCs must grapple with unique constraints related to the populations they serve, the services they provide, and how they are funded. They provide care to about 1 in 6 Medicaid beneficiaries nationally, and Medicaid accounts for 42% of their revenues.1

CHCs face significant financial headwinds. While FQHCs receive core federal funding to care for uninsured patients and deliver uncompensated services, that funding—adjusted for inflation—has decreased over time.6 In Medicaid, CHCs are paid under a prospective payment system (PPS), in which they receive a single, bundled rate per visit regardless of the volume or intensity of services provided at that visit. In theory, this payment system should provide CHCs with a stable funding stream, but payment rates have not kept pace with increasing costs. Instead of PPS, states can participate in “alternative payment models,” which often involve capitated payments to CHCs by Medicaid managed care organizations. States are required to provide “wraparound” payments to CHCs when Medicaid managed care rates are not equal to PPS payments, but delays are common and the reconciliation process is long and complicated.7 These payment gaps contribute to the patchwork of funding that CHCs must rely on.

As a result, CHCs operate on thinner financial margins than many other parts of the health care system. Their bottom lines have worsened recently, as COVID-related supplemental funding expired, and Medicaid “unwinds” the continuous eligibility rule that was instituted during the public health emergency. The latest data show that net financial margins for health centers reached a low of 1.6% in 2023.8 Almost half of CHCs experienced losses, and experts predict that most CHCs will have negative margins in the next few years.

These chronic and acute financial constraints have cascading effects on recruitment and retention of CHCs’ workforce and on capital investments to improve care.9 Success under VBP models requires investment in personnel and infrastructure, which is especially difficult for CHCs given their baseline financial constraints.

Penn LDI has developed the following recommendations for public and private payers to address some of these challenges in providing value-based care in CHCs. These recommendations were developed through a series of focus groups with frontline CHC leadership and staff, conversations with national leaders on CHC payment and policy, and review of peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed literature.

We focus our recommendations on two distinct but related areas: first, we discuss opportunities to promote participation and success of CHCs in VBP; second, we discuss opportunities to align quality measurement and VBP with goals of value-based care and population health equity.

About 40% of CHCs participate in some form of VBP, although VBP accounts for less than 5% of CHC revenues.10 To drive value-based transformation of care, VBP programs must attract more CHCs and make it more feasible to participate.

Current VBP programs include many different quality measures, making success across all of them difficult. Some commonly used quality measures may not be relevant to the typical care that CHCs provide. These challenges are magnified among CHCs participating in multiple VBP programs under different payers.

CHCs may be better positioned to participate in VBP programs that incorporate quality measures they already collect. CHCs with federal funding must report performance on 15 quality measures through the Uniform Data System.11

Another promising initiative is the Core Quality Measures Collaborative, a public-private partnership working to align quality measures across payers.12 Its proposed Consensus Core Set partially overlaps with the Uniform Data System and includes a wider array of measures.13 By using a standard set of measures, payers and VBP programs can reduce the reporting burden that presents an obstacle to CHC participation.

Achieving value-based care requires a robust workforce. However, CHCs have high rates of staff turnover and burnout, which can affect quality of care.14-17 Due to the fixed nature of federal grant funding and PPS payments and their limited liquid capital, CHCs lack the same ability as the private sector to rapidly adjust to market trends in workforce recruitment and retention. Without adequate workforce support, CHCs cannot effectively participate in VBP programs.

It is critical that Congress re-authorize and increase federal FQHC grant funding at levels that can sustain and retain a robust clinical and administrative workforce. Workforce support should include competitive wages, expanded benefits, upskilling programs, career mentoring, and ladders for advancement.18 Expanding Medicaid coverage and increasing Medicaid reimbursements to CHCs can also provide revenues to bolster the workforce.

Most CHCs will also need technical assistance and financial forecasting tools to understand their readiness to participate in VBP programs, and to contract with payers. Technical needs assessments and resources are available through the National Association of Community Health Centers for member FQHCs, rural health clinics, and similar mission-oriented institutions.19 Networking across CHCs can be an effective way of sharing resources and negotiating VBP contracts. For example, Missouri Health Plus, a network of 22 FQHCs, has value-based care contracts with the state’s three Medicaid managed care organizations, covering more than 200,000 attributed members; and the FQHC-led Community Care Cooperative in Massachusetts is now the state’s largest Medicaid accountable care organization (ACO) and has established contracts for Medicare and commercial payers as well.20 It has branched out into building capacity in FQHCs though operational support and electronic health records.

Upfront investments can help recruit CHCs to VBP programs and transform care. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has built this approach into some VBP programs, including the Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) Model and Advance Investment Payments through the Medicare Shared Savings Program.21,22

Other payers can learn from newer CMS models that provide upfront investment to encourage CHCs to participate in Medicare ACOs, such as:

• the ACO Primary Care Flex Model, which includes an Advanced Shared Savings Payment of $250,000 to cover costs of forming an ACO and administrative costs for required model activities;23

• the “health equity benchmark” established under the ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Model, in which participating ACOs receive an additional $30 per Medicare beneficiary per month for serving underserved beneficiaries.24

The precarious financial situation of many CHCs precludes widespread participation in VBP programs. PPS rates have not kept pace with operational costs, and Medicaid’s wraparound and reconciliation process can cause severe cash flow problems for CHCs with thin margins.

Many state Medicaid programs have not updated their cost basis for many years, nor have states updated their formulas to reflect the expanded scope of services or new ways of delivering services.25 Rebasing Medicaid PPS rates should be a priority for states. Further, states should explicitly mitigate “wraparound” payment delays in their alternative payment methodologies. For example, North Carolina has recently implemented real-time wraparound payments in its latest state plan amendment, requiring managed care plans to reimburse CHCs for both the negotiated rate and wraparound payments upon initial claims adjudication.26

Achieving population health equity is aligned with the goals of value-based care. This is because effectively addressing the structural drivers of health disparities requires a comprehensive understanding of the patient and the context in which they live, work, and use health care. CHCs are frontline providers in service of the goal of population health equity. They care for low-income populations at disproportionate risk for adverse health outcomes and frequently offer services to address the social determinants of health, which can have more substantial impact on health outcomes than health care itself. Existing VBP models often do not capture progress toward population health equity goals or management of health-related social needs, such as employment, stable housing, healthy food, and transportation. Acknowledging and measuring progress toward these goals can make VBP more relevant to the CHC context and move us toward a health care system that provides value-based care.

Few VBP models incorporate measures of population health equity into their definitions of “value,” but interest is growing in bringing an equity focus to payment reforms. Population health equity can be measured across many dimensions (e.g., relative measures such as closure of racial and ethnic health gaps, or absolute measures such as improvements in quality of care for low-income populations from a baseline period).27 Consensus on a given measure can be achieved through partnership among CHCs, patients, community leaders, and payers. The Center for Health Care Strategies released a brief outlining how payers can embed health equity into VBP model design.28 Transparent, collaborative efforts to define equity and its objectives can refocus VBP efforts on patients and their priorities to further value-based care.

Payers are exploring ways to incentivize and reward health equity. For example, Minnesota’s Medicaid program has established the Integrated Health Partnerships program in which it bases 20% of an ACO’s quality score, which affects providers’ payment, on reducing racial and ethnic disparities within select measures.29 In commercial plans, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts has adopted a pay-for-equity program in which ACO contracts reward achieving equity in outcomes.30 Many programs are in the early stages of simply measuring disparities, but measurement is critical for understanding the mechanisms behind disparities and designing value-based care that centers the patient and their life context.

Value-based care must consider and address health-related social needs. Recognizing these needs allows organizations to identify barriers to accessing or maximizing the benefits of clinical care for patients. CHCs have long been at the forefront of screening and referral for health-related social needs. About 70% of CHCs report collecting data on each patient’s social risk factors, with 60% of them using a standardized screener.31 The most commonly used screener is the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’Assets, Risks and Experiences (PRAPARE®), a standardized tool developed in part by the National Association of Community Health Centers.32

Increasingly, health care providers are screening patients for health-related social needs, but it is rarely linked to closed-loop management plans to address those needs. To improve quality of care and outcomes and provide value-based care, providers must have adequate reimbursement for screening, access to comprehensive and integrated screening tools, and sufficient clinic and community resources for referrals and follow-up.31 Many states have started using Medicaid waivers to pay for services that meet health-related social needs, such as food deliveries and temporary housing.33

Through VBP, payers can incentivize and reward management plans that are linked to screening for health-related social needs. For CHCs, payers can incorporate PRAPARE into VBP programs to standardize measurement in ways that address the needs of local populations. They can reward CHCs for documented referrals to community-based organizations; health care savings should be captured and shared with the CHCs and the community-based organizations to maintain and enhance their capacity to meet these needs.

Because health outcomes are inextricably linked to the social determinants of health, cross-sector partnerships are key to promoting population health equity.2 For example, state and federal agencies with the funding and responsibility to address the social determinants of health, such as education, housing, and employment, may benefit from formal relationships with CHCs. These partnerships may present opportunities to share funding and resources with CHCs that are already intervening on these determinants downstream.

Such efforts can be supported through Medicaid Section 1115 waivers. For example, North Carolina’s waiver supports bidirectional referrals between health services organizations and community-based organizations.34 VBP programs could re-invest any savings into building health system partnerships with governmental agencies or community-based organizations. Expanding traditional concepts of value in this way often requires cultural change on the part of payers and providers. Many CHCs have already adapted to this change by virtue of the patient populations they serve and can be recognized and rewarded for doing so.

The National Committee for Quality Assurance has developed a series of Health Equity Accreditation programs that can facilitate this type of cultural change or allow organizations to be recognized for their commitment to health equity.35 Such accreditation programs can be incorporated into VBP programs to further population health equity. A number of states are now requiring that Medicaid managed care organizations have equity accreditation; on a local level, the Independence Blue Cross Foundation in Pennsylvania has helped CHCs in achieving this accreditation.

Our recommendations are designed to improve the ability of CHCs to participate in existing VBP arrangements and modify these arrangements to promote value-based care in CHCs. But a recurrent theme in our conversations with CHC stakeholders was the need to re-examine resource allocation and consider longer-term structural changes to improve the health of low-income populations. Effectively addressing the drivers of health for patients served by CHCs requires considering the upstream forces that shape broader living conditions and influence how health care is organized. Improving outcomes for low-income patients will require multidisciplinary interventions outside of health care in the fields of education, employment, housing and urban development, and energy. These structural interventions can range from narrow to broad, depending on the political will and context. CHCs are well-positioned to collaborate with other sectors to address these upstream forces, but it will require a fundamental reconceptualization of how CHCs are valued and paid.

This issue brief was supported by the Independence Blue Cross Foundation.

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Research Brief: Shorter Stays in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Less Home Health Didn’t Lead to Worse Outcomes, Pointing to Opportunities for Traditional Medicare

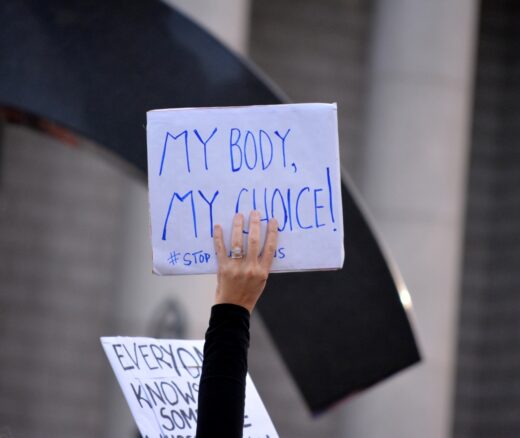

How Threatened Reproductive Rights Pushed More Pennsylvanians Toward Sterilization

Abortion Restrictions Can Backfire, Pushing Families to End Pregnancies

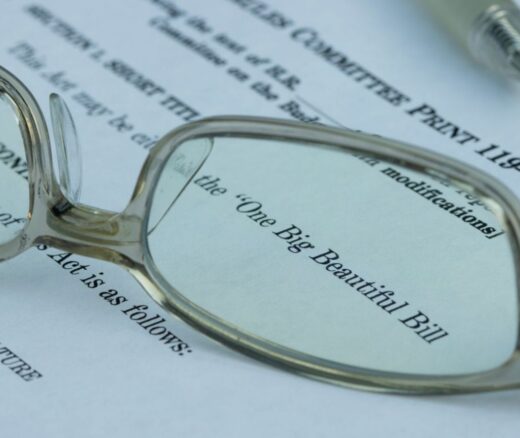

They Reduce Coverage, Not Costs, History Shows. Smarter Incentives Would Encourage the Private Sector