One Agency’s Maps Are Known For Documenting Redlining

But Many Other Factors Played a Role in Denying Loans, LDI Fellow Says

Population Health

Blog Post

Across the United States, deaths from firearm injuries are a growing crisis. In 2019, the United States outstripped all other nations except Brazil in firearm deaths. For comparison, that same year, there were 767 gun-related deaths in Canada, 262 in Australia, 792 in Italy, 155 in the United Kingdom, and 160 in Sweden. In 2020, 45,222 Americans were killed by a firearm, including 24,292 from suicide and 19,383 from homicide.

The U.S. numbers are high any way you look at them, but the national data, taken as a whole, obscure local variations in firearm deaths. Indeed, local data can vary greatly, and understanding why may point to causes and solutions. Our team took a deep dive into geographic variation in firearm homicide and suicide to identify counties that had unusual increases or decreases over a 30-year period.

As we recently reported in JAMA Network Open, we used geospatial mapping and initial rates of firearm deaths to predict rates of firearm deaths in each U.S. county a few decades later. We then compared these predicted rates to actual rates in recent years to identify counties that behaved unexpectedly. Since these identified counties deviated from their predicted firearm death rates, we suspected that they might have unique characteristics that would provide insight into opportunities for prevention.

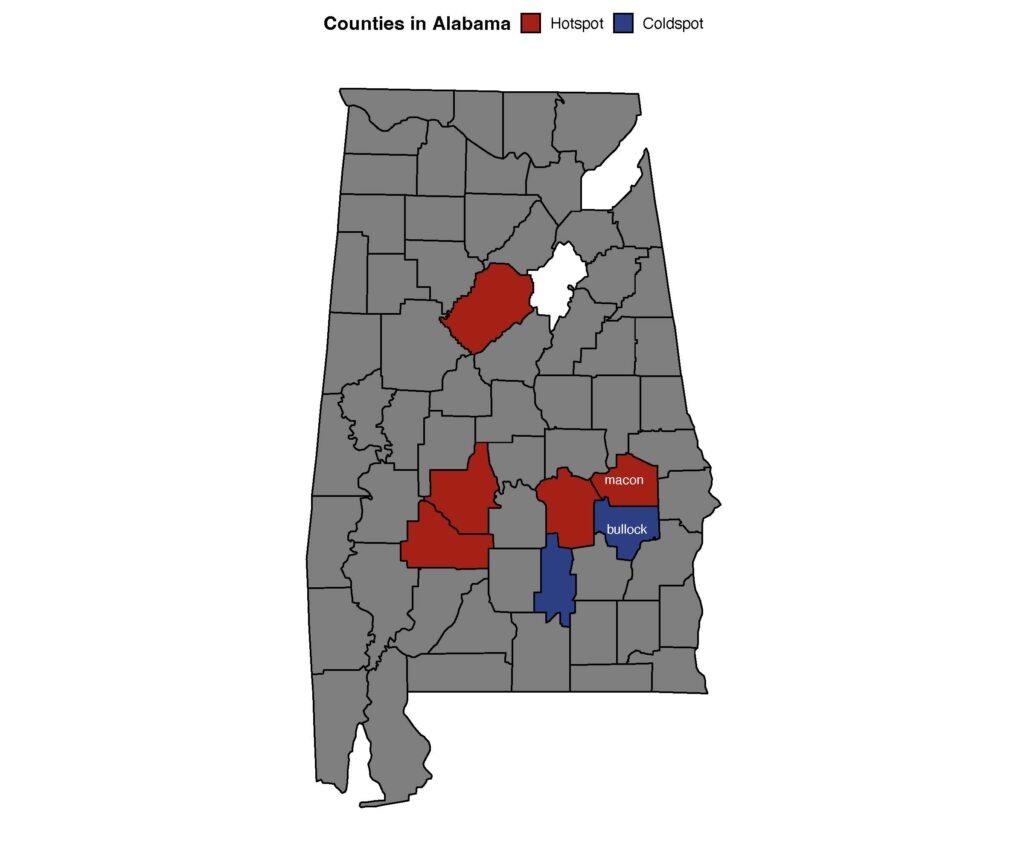

Overall, we found more hot spots, showing unexpected increases in firearm deaths over time, than cold spots, showing unexpected decreases. The hot and cold spots are scattered across the country, in both rural counties and urban counties and in both blue states and red states. However, we did find some broad patterns. Firearm homicide hot spots were clustered in the southeast, especially Alabama, while firearm suicide hot spots were in more rural regions in the West and Midwest. We also found that, compared to cold spots, hot spots were in poorer areas and had more firearm availability.

Zooming in on the counties themselves, we found a success story in Washington, D.C., where the firearm homicide rate decreased from 56.5 to 14.5 per 100,000 between the beginning of the 1990s and recent years. In contrast, just 35 miles away in Baltimore, the rate has gone in the opposite direction, and firearm homicides in Baltimore alone now account for 67% of firearm homicides in all of Maryland.

Meanwhile, in Alabama, two adjacent counties stood out. Both rural with similar-sized populations, one was a hot spot, with high rates of firearm homicide, and the other a cold spot, with reduced rates of firearm homicide.

Findings like these give us a real starting place to investigate what might make these neighboring counties similar and different. Is it policy, economics, and programming? Is it interagency coordination or leadership? We are starting to find out.

We will only make progress in answering these questions—and ultimately in reducing firearm death and injury—by investing resources in tackling firearm violence as a public health problem. For the first time in decades, researchers are seeing new funding and opportunities to get to answers questions about firearm injuries. We conducted the research we reported in this study with support from a new funder, the National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research. Although firearm injury has been historically underfunded, federal funders have also recently begun to allocate the needed resources to dig deep into these problems. As researchers, we are responsible for seizing this opportunity to advance the science to prevent firearm deaths.

But there’s more that is needed: For the solutions we already know exist, and for those we are about to discover, we will also need the moral courage and political will to enact policy and programming at a scale that will protect the vulnerable from firearm injury and death.

The study, “County-Level Variation in Changes in Firearm Mortality Rates Across the US, 1989 to 1993 vs 2015 to 2019,” was published June 6, 2022, in JAMA Network Open. Authors include Michelle Degli Esposti, Jason Gravel, Elinore J. Kaufman, M. Kit Delgado, Therese S. Richmond, and Douglas J. Wiebe.

But Many Other Factors Played a Role in Denying Loans, LDI Fellow Says

Offit and Buttenheim Criticize HHS Placebo Trial Mandate as Unethical, Misleading, and a Threat to Vaccine Confidence

A Penn LDI Virtual Seminar Explores the Latest Trends in Anchor Institution Operations

Neighborhood Perceptions May Also Affect PTSD and Depression Recovery After Serious Injury

A Penn LDI and Opportunity for Health Lab Virtual Seminar Explores Economic Assistance Programs

Testimony: Delivered to Philadelphia City Council