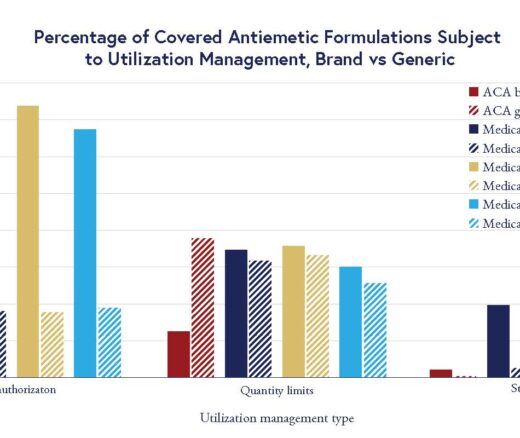

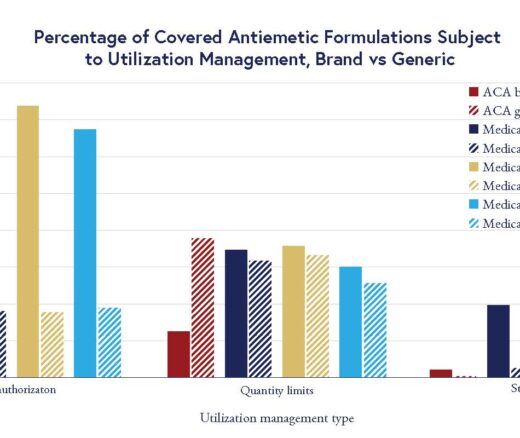

Insurers’ Utilization Management Tools Vary Widely on Anti-Nausea Drugs for Cancer

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Blog Post

Many adults and their children have a terrible problem when they try to use Medicaid insurance: They can’t find a doctor to accept them as patients.

That barrier can block basic primary care for women and children and for other Medicaid recipients who are low-income, older or disabled. There are many clues why. The paperwork burden is high. Insurance denials can be troublesome. And some states have failed to raise Medicaid doctors’ pay for decades. Its average pay is the lowest of any insurer, including Medicare. With all those concerns, doctors may need an altruistic streak to participate.

But LDI Senior Fellow Diane Alexander thinks she has a more straightforward solution: Pay primary care doctors more for treating Medicaid patients.

Just increasing pay by $10 for services like office visits improved access for adults and children, according to her study in the American Economic Journal with Molly Schnell of Northwestern University. Raising pay by $45—which closed the gap with commercial insurance—completely eliminated the access problem for children and cut it by more than half for adults.

Those higher payments also led to lower school absenteeism for children.

Results like these make pay increases “the number one obvious thing to do if the goal is to increase access for Medicaid patients,” Alexander said. “Many doctors are paid far too much but not for treating these patients. We should increase payments to provide more access for Medicaid beneficiaries, which also leads to more utilization and improved health.”

Alexander’s interest in health care payments runs deep. She was a Federal Reserve Bank economist in Chicago before becoming an Assistant Professor of Health Care Management at Penn’s Wharton School in 2021.

Along the way she learned that doctors respond to incentives, but often in unexpected ways. In her PhD at Princeton University, she analyzed a New Jersey program that paid doctors bonuses if they cut costs on Medicare patients. Many doctors got around the program’s intent because they practiced at multiple hospitals and simply transferred their healthiest patients to the centers with the bonuses.

Alexander has also worked on the environmental effects of pollution. Her 2022 study looked at the Volkswagen emissions scandal in which the auto maker falsely claimed it was selling ‘clean’ diesel cars when they were just triggering secret equipment during emissions tests to cut emissions only at that moment. Her study with Hannes Schwandt of Northwestern University found that counties with growing shares of cheating cars also had increases of 1.7% in infant mortality and an 8% jump in children’s ER visits for asthma.

Alexander’s foray into Medicaid payments was made possible by a big policy change. In 2013 and 2014, the Affordable Care Act required all states to raise primary care doctors’ pay to the same level as Medicare.

States have wide leeway to set Medicaid rates. So the hikes sent pay soaring by 60 percent overall for selected primary care services, representing “one of the biggest changes to payments that we’ve ever seen,” Alexander said. Ten states more than doubled their payments to primary care doctors.

Even a $10 increase had a noticeable effect, raising the percentage of Medicaid members who could see doctors and report they were in good health. That $10 increase would also cost $60 million and raise average state Medicaid spending by less than 1 percent, the paper estimated.

The federal government funded the two-year bump, which ended in 2014. Only 14 states went on to pay at least half of the increase. Researchers saw the treatment gains fall back in states that stopped paying the increases.

Alexander said she was most surprised by the drop in child absenteeism. A $35 increase would cut chronic absenteeism by over 10 percent, the study found. The decline was most pronounced in younger children, where absenteeism is more tightly linked with illnesses, she said.

Congress is now preparing to make deep cuts in Medicaid to save $880 billion over 10 years in part to fund expiring tax breaks for wealthier people.

The effects could be profound because Medicaid’s reach is vast, covering 40% of all children and childbirths, most nursing home care, and all federal spending on home- and community-based services. Medicaid is also a big player in mental health, drug treatment, and HIV care.

“Medicaid is already underfunded and always first on the chopping block,” Alexander said. “It doesn’t have a powerful constituency, so it’s easier to cut.

Large cuts “are going to hurt a lot of vulnerable people.”

The study, “The Impacts of Physician Payments on Patient Access, Use, and Health,” was published in July 2024 in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. Authors include Diane Alexander and Molly Schnell.

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

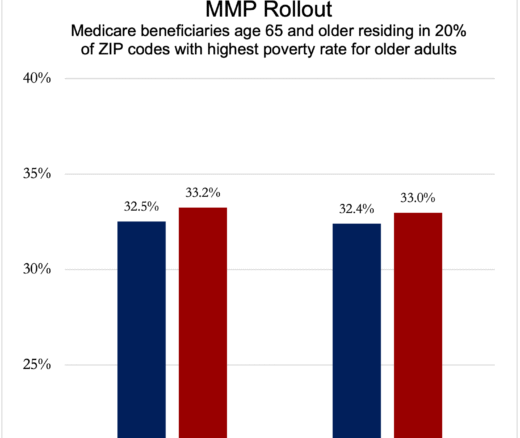

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Research Brief: Shorter Stays in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Less Home Health Didn’t Lead to Worse Outcomes, Pointing to Opportunities for Traditional Medicare

How Threatened Reproductive Rights Pushed More Pennsylvanians Toward Sterilization