Only One in Four High-Risk Rural Births Get Appropriate Hospital Care

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

Improving Care for Older Adults

News | Video

Since its launch 41 years ago, the Medicare Hospice program that covers the costs of care for terminally ill patients has exploded in size. One-fourth of Medicare spending now goes to hospice care as half of all the people who die are Medicare beneficiaries using the program. In 2000, there were 500,000 hospice users. There are now 1.8 million. The annual Medicare spending in that same period has gone from $3 million to $23 billion.

Perhaps more importantly, in 2000 one-third of all hospice agencies were non-profit. Today, 75% of all agencies are for-profit. It’s reported that well-managed non-profit hospice agencies yield an annual profit margin of about 5%-to-6% while for-profit public or private equity agencies yield about 18%-to-22% percent profits.

In recent years, the for-profit-dominated industry has been the subject of investigations and exposés questioning quality standards and financial practices.

In opening the March 1 University of Pennsylvania Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics’ virtual seminar on hospice issues, LDI Executive Director Rachel M. Werner, MD, PhD, noted that “there are ongoing concerns that hospice’s eligibility and payment systems do not support consistent, high-quality care. They encourage profits over patients and result in inequitable access to end-of-life care. Medicare’s hospice benefit has become a topic of concern for policymakers.”

Moderator Werner was one of five top national experts in the field of hospice care who convened for the seminar that was entitled, “Hospice Payment: What’s Broken, What Works, and What’s Next.” The other four included Ira Byock, MD, Fellow and past President of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Care Medicine; Mary Ersek, PhD, RN, LDI Senior Fellow and Penn School of Nursing Professor of Palliative Care; Kimberly Sherell Johnson, MD, Senior Fellow in the Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development at Duke University; and David Stevenson, PhD, Professor and Chair of the Department of Health Policy at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

The Medicare hospice benefit is separate from the overall curative care provided through Medicare or Medicare Advantage. It was narrowly designed to improve the end-of-life experience for terminally ill beneficiaries with a secondary goal of reducing the cost of health care services at the end of life. Hospice is not an automatic benefit. A patient’s condition must be certified as likely to result in death within six months by both their own physician and a hospice physician. More importantly—and controversially—in order to qualify for hospice, the patient must agree that they will forgo any disease-directed or curative therapies for their terminal condition. They must acknowledge that they are dying and don’t expect any care beyond that which comforts their further drift toward death.

“Hospice is a transition in the philosophy of care, and this has been a barrier to some people enrolling in hospice,” said Vanderbilt’s Stevenson. “Upon hospice selection, the hospice agency takes over all care related to the terminal condition. They receive a per diem payment to manage that, whether it’s medications, direct care services, durable medical equipment, and anything else related to the terminal condition. Benefit payments are not adjusted for diagnosis, so people with cancer, heart disease, dementia, COPD, etc., all have the same benefit. The payment to the hospice agency is the same for a patient who is in home care as for a patient who is in a nursing home.”

The panelists’ discussion of hospice issues ranged over a variety of topics, some of which were racial and ethnic disparities in the program, the availability of adequate metrics that accurately reflect the quality of care, the need for a Medicare Advantage “carve-in” for hospice, and the rigid separation between hospice and general care that denies patients the option to receive curative care treatments at the same time they are participating in hospice care.

This last issue is closely connected to the hospice racial and ethnic disparities issue, according to Duke University’s Johnson. “It is a benefit you must select in lieu of life-extending services,” she said. “But we know that as a group, Black Americans are more likely to want life-prolonging therapies even when prognosis is poor. So, hospice may not be consistent with their values and goals and that really creates issues of access. If people are still wanting to receive blood transfusions which may be life extending, or even dialysis, those things are not generally part of the hospice package as it is currently reimbursed. I think that drives not just lower rates of enrollment, but higher rates of disenrollment for people who are members of minority racial and ethnic groups,” she said.

And that’s just one area of the larger health equity issue for hospice, according to Johnson. “There is tons of data documenting lower rates of hospice use for individuals from minority racial and ethnic groups,” she said. “There’s been enormous growth in hospice, yet these gaps in use based on race and ethnicity still persist.”

“In the last Facts and Figures Report by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) you see that about 50% of Medicare beneficiaries who died in 2021 used hospice services,” Johnson continued. “If you look at that number among Black and Hispanic individuals, only about a third of those who died during that same year used hospice services. So, you see this huge gap. Another way that we look at that is relative to representation in the general population. We know that compared to their representation in the general population that white individuals are actually overrepresented among hospice participants as compared to Black or Hispanic individuals. For instance, Black individuals make up about 8% of all hospice enrollees, but they represent about 12% of the US population. And when you think about the fact that the diagnoses that are more common among hospice enrollees—like cancer, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s disease—are more common for these minority racial and ethnic groups, the disparities are actually even larger than they appear.”

Another central issue in the discussion was whether hospice quality measures are adequate or accurately reported. Penn Nursing School’s Ersek pointed out that there are four hospice quality measures systems:

• 1. Hospice Quality Reporting Program, implemented as part of the Affordable Care Act in 2014.

• 2. Hospice Visits Last Days of Life (HVLDL) introduced in 2017.

• 3. Hospice Care Index implemented in 2022.

• 4. Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) Hospice Survey implemented in 2015.

She noted that while these systems exist, there are wide variations in how they are applied, gamed, or even avoided by hospice agencies.

“One caveat is that hospice is focused on home care and most of the care is provided by family caregivers when the patient is in their home,” said Ersek, an LDI Senior Fellow. “The number of hospice patients whose primary residence is in a nursing, or an assisted living facility has grown exponentially. Hospice agencies can’t always control the quality of care that occurs because it is delivered by staff in those facilities. It’s a challenge to tease out the relative contributions between the care that hospice gives and the quality of that care versus the end-of-life care that a nursing home or assisted living staff provide. And we don’t really have a good way to tease these out and that is a major issue.”

“Another caveat is that many hospice agencies are exempt from reporting, often because they’re too small or they’re too new,” said Ersek. “There were 300 new hospices that came on board between 2020 and 2021. That’s not a huge number in the overall number of 5,800, but it is one that continues to grow a lot. So, to gauge how common it is that these outcomes are not reported, I logged on to Care Compare for a zip code in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. There were 38 hospice agencies there. Of those 38, 18 had missing quality data (47%). That’s a lot. It’s a huge gap in our understanding of the quality of hospice care writ large as well as the quality of care that specific agencies deliver.”

Another area of potential hospice reform that has been getting increased attention is its relationship—or lack thereof—with Medicare Advantage (MA). Historically, hospice care was “carved out” of MA. In the last few years, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) tested the potential reversal of this policy with a “carve-in” for hospice in MA. The results are said to be “promising” but CMS has announced it will be ending this program at the end of 2024.

“If a Medicare Advantage enrollee elects hospice, the hospice agency and not the MA plan is responsible for all services related to the terminal condition,” said Vanderbilt’s Stevenson. “That has given MA plans a bit of an out in terms of not having to remain responsible for individuals with serious illness needs who elect hospice. The MA plan can instead encourage those patients to enroll in hospice so it’s not responsible for providing those services.”

“The ‘carve-in’ does the opposite and make hospice services part of the MA coverage,” Stevenson continued. “A potential conceptual advantage of that is that an individual wouldn’t have to make a choice somewhere along the way to enroll in something else. The MA plan could manage their serious illness as the need arises, as opposed to paying attention to prognoses or forgoing curative therapies. In theory, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) pushed that as the way to go in 2014 and I think it good be a good idea but we also have reasons to be concerned and need to make sure we have sufficient safeguards in place.”

Offering a historical perspective of the hospice program, Byock looked back at the late 1970s when the concept of hospice was more of a social movement than a care delivery model. It was a time when physicians didn’t feel they had a role once a patient was deemed to be dying.

“Hospice was originally driven by nurses who were tired of watching people die badly, often in hospitals, often in pain, and too often alone,” said Byock. “So the nurses and a few renegade doctors began developing a model that provided end-of-life patients with better continuity of care. It was almost totally non-profit in the beginning as a volunteer model program that gradually evolved into a more professional model and that hired interdisciplinary teams of doctors, nurses, social workers and chaplains.

“When the for-profits began in the mid-to-late 1990s, I was actually a champion for them because I thought it was a highly efficient way to develop high-quality, high-functioning, programs delivering a reasonable return on investment,” said Byock. “But those initial for-profit programs were wholly owned by individuals or families that were zealots for access to services and quality of care. But in the early 2000s, some of the very best for-profit programs went through initial public offerings and became publicly traded. After that we watched the hospice quality spiral down and the attitudes of the new management focus on finances.”

“Today I fear we’re seeing the death knell of hospice in America,” said Byock. “There are still plenty of excellent programs but we’re also seeing huge variations in quality. Many of the for-profits maintain their high profit margins by skimping on services, tolerating unmet need among the dying patients they serve, shifting costs to families, short staffing on nurses, maintaining unreasonably high caseloads, and short staffing doctors. We’re watching doctors go away from hospice care. It’s such a cruel irony to know that in the beginning we created hospice in part to ensure dying patients had access to physicians. Now a number of hospice programs have themselves become the barriers to dying patients being able to access their doctors.”

“I am not against for-profit hospice care,” Byock continued. “I’m an American and a capitalist. I think there is a place for for-profit hospice care, but those programs must succeed by delivering consistently high-quality care and, unfortunately, that’s not what we’ve seen.”

As the session ended, Werner asked the panelists for a final comment identifying one positive trend or development that makes them optimistic about the potential to improve hospice care. These are their answers:

Byock: Hospice is a brilliant model of human caring so we shouldn’t give up on some of the reforms and metrics we’ve been discussing, and we should highlight what goes well. For instance, the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) model deserves continued attention because hospice skills and knowledge could be integrated more deeply into this program for frail, dually eligible patients.

Johnson: While I’ve highlighted some of the gaps and disparities in hospice use, the fact is that there’s really been a substantial increase in the use of hospice services among all groups, even though there still are differences between advantaged and disadvantaged groups—and that does suggest increased access, even with all the issues we’ve identified.

Stevenson: Hospice has improved end-of-life care for millions of people over the course of its history. It’s just that its chassis is pretty outdated at this point. I think the CMS Hospice Outcomes and Patient Evaluation (HOPE) program will be another tool in the toolbox that will be useful. And there are the palliative care models that have been developed for outpatient care that hopefully can be integrated a bit better with hospice as payment reforms go forward.

Ersek: Integrate hospice more into overall health care. Within the Veterans Health Administration (VA) we’ve integrated all aspects of end-of-life care fairly seamlessly in ways that don’t require terrible choices about where one receives care. Also, we should be mindful that about 81% of people who are asked rate the quality of hospice care received by their family members as excellent. So, we’re not doing everything wrong.

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

Former CMMI Leader Liz Fowler Cites Rigid Federal Scoring Rules and Bureaucratic Impatience for Pilot Failures

A Major European–U.S. Hospital Study Finds That Changing How Hospitals Are Organized Reduces Burnout and Turnover While Improving Care Quality

An LDI Fellow Who Helped Architect the ACA Highlights Progress on Primary Care Payment Reform and the Expansion of Site-Neutral Reimbursement Policies

Penn LDI Senior Fellow Dominic Sisti Cites “Alarming Levels”

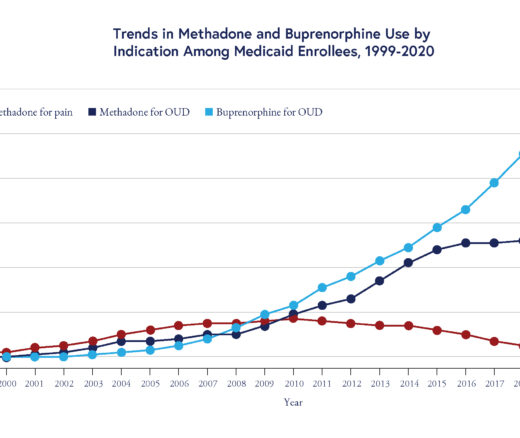

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication