How Medicaid Cuts Could Force Millions Into Nursing Homes

If Federal Support Falls, States May Slash Home- and Community-Based Services — Pushing Vulnerable Americans Into Nursing Homes They Don’t Want or Need

Improving Care for Older Adults

Brief

The costs and quality of post-acute care (PAC) have come under increasing scrutiny for the value they provide to the nearly 40% of patients receiving specialized nursing or rehabilitation after hospital discharge. Much of this scrutiny focuses on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), which account for a disproportionate amount of spending. The stakes are high for Medicare, the primary payer of post-acute services, for the nursing home industry, which relies on these short-stay patients to subsidize long-term residents, and for patients and families themselves. This Issue Brief reviews Medicare coverage and payment policy around PAC, trends in utilization and costs in SNFs, and what we know about quality and outcomes. We recommend ways to improve the value of these services through payment policies that align incentives across payers and settings.

PAC is primarily delivered in three settings: in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), at home with visits from home health agencies, and in inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs). Across settings, Medicare is the primary payer for PAC, and the vast majority of this spending occurs in SNFs and in the home (Figure 1).1 This care comes at a high cost to Medicare. In 2021, traditional Medicare spent $28.5 billion on SNFs (14% of Medicare Part A’s funding pool), for treatment of 1.2 million individuals.2

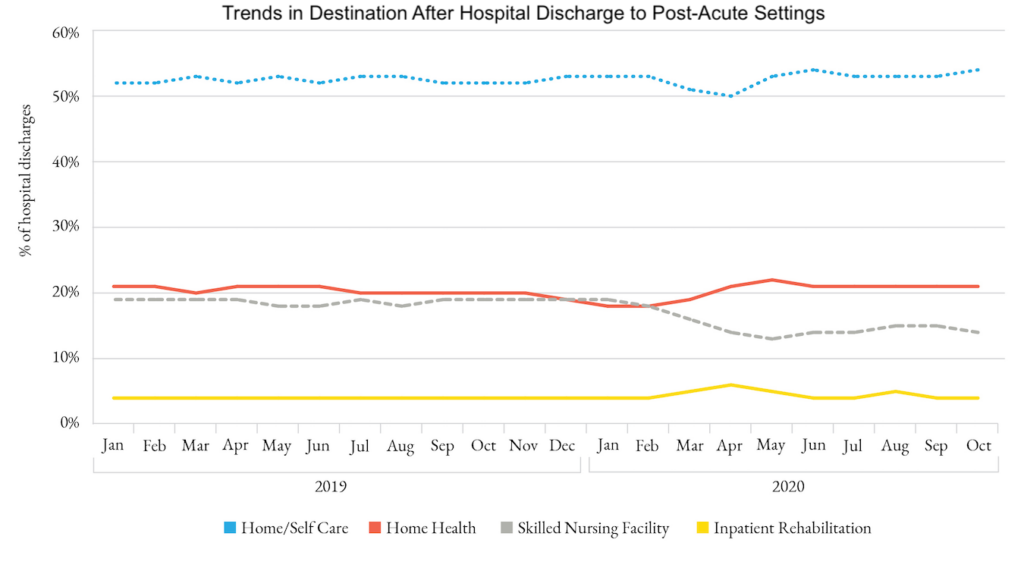

For decades, the use of PAC after hospital discharge increased as the length of hospital stays decreased. This increase was particularly pronounced in institutional PAC, where rates of utilization after hospital discharge grew from 21% in 2000 to 26% in 2015 among patients enrolled in traditional Medicare.3 More recently, however, PAC has shifted from institutional to home-based settings as payers seek lower-cost alternatives to nursing homes. The pandemic accelerated this shift in PAC away from SNFs and toward home health, as the percentage of hospitalized patients 65 and over discharged to SNFs declined from 19% to 14% from January 2019 to October 2020 (Figure 2).4 At the same time, the share of PAC spending in SNFs dropped from 39% to 31%.

The shift away from SNFs has important implications for the nursing home industry, which relies on generous Medicare PAC payments for short-stay patients to subsidize their long-term residents, who are primarily covered by Medicaid. Medicare payments are quite lucrative. In 2021, traditional (fee-for-service) Medicare paid a median of $556 per day and $23,797 per stay; according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), nursing homes have an average marginal profit of 26% on these Medicare payments.2 Despite the shift to home-based care for PAC, payment to SNFs still represent a significant percentage of Medicare costs.

Medicare pays SNFs on a per-diem (daily) rate. When Medicare was passed in 1965, it included some coverage restrictions for SNFs designed to reduce overutilization of this expensive service.6 These restrictions include requiring that beneficiaries have a minimum stay of three days in a hospital to qualify for coverage in a SNF; paying for a maximum of 100 days of SNF care per benefit period (an acute illness episode); and requiring a large daily patient copayment starting on day 21 of a SNF stay. Traditional Medicare has retained these rules, while some Medicare Advantage (MA) managed care plans, accountable care organizations (ACOs), and other newer payment models have opted out of these restrictions. In addition, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) waived the 3-day prior hospitalization rule in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. We now have evidence about the effects of some of these rules on health care utilization and quality.

Evidence from MA plans suggests that the 3-day rule inappropriately lengthens hospital stays for some Medicare enrollees. Comparing plans that did and did not eliminate the 3-day rule, one study found a 0.7 day decrease in hospital length of stay for patients enrolled in plans that eliminated the rule, with no increase in number or length of SNF stays.7

Meanwhile, within traditional Medicare, the 3-day rule appears to encourage overuse of SNFs, based on a comparison of day two and day three discharges, while also leading to higher 30-day hospital readmission rates.8 This research suggests that eliminating the 3-day rule could save Medicare about $345 million a year (1.1% of total Medicare SNF payments).

In the first year of COVID-19, despite the waiver, SNF use after hospital discharge dropped as the pandemic hit nursing homes hard.4 However, PAC episodes provided to long-term care residents without a preceding hospitalization (a process known as “skilling in place”) increased by 77%, with no appreciable change in Medicare’s monthly spending on SNF during the pandemic ($2.1 billion before the pandemic versus $2.0 billion during the pandemic).9

Another feature of traditional Medicare’s SNF payment policy is the patient copayment ($200 per day in 2023) starting on day 21 of a SNF episode. This payment structure has received scrutiny for its impact on length of stay, in particular for patients without supplemental coverage or Medicaid. Medicare beneficiaries are commonly discharged from SNFs on day 20 of their SNF stay, right before the copayment kicks in, and those discharges are more common among individuals who are racial or ethnic minorities or who live in poorer areas.10 This spike in discharges on day 20 is associated with shorter SNF stays, higher hospital readmission rates, and higher Medicare spending after discharge.11 This suggests that the copayment policy may have unintended and negative effects by encouraging discharge from a SNF sooner than medically indicated.

At the same time, traditional Medicare may also create incentives for SNFs to extend certain stays because of its generous per-diem payments without patient cost sharing through the 20th day of the SNF stay. While research has found that one additional day in a SNF results in a slightly lower likelihood of rehospitalization within 7 and 14 days after SNF discharge (by 0.15 percentage points and 0.1 percentage points respectively), these benefits wane by 30 days after SNF discharge. Medicare’s savings stemming from lower rehospitalizations are small and do not offset the cost of the additional day in a SNF, resulting in an increase in total Medicare payments of $371.12 Notably, longer SNF stays are more valuable for clinically complex patients than for the average beneficiary.

When Medicare began in the 1960s, it paid most SNFs on a reasonable cost basis. In 1997, with the passage of the Balanced Budget Act, traditional Medicare implemented a prospective payment system for SNFs. These prospective pay rates were adjusted for case mix and geographic variation in wages and were designed to cover all costs of SNF care. This case-mix adjustment heavily weighted payments by the volume of therapy services provided, increasing per-diem rates for more intensive therapy services. Then, in October 2019, Medicare replaced this case-mix adjustment with a new model, called the Patient Driven Payment Model (PDPM), in an attempt to incentivize value over volume.2 The PDPM model removes therapy minutes as the driving force for payments, instead focusing on clinically relevant factors that account for medical complexity and functional status.2 According to MedPAC, the number of therapy minutes dramatically declined between January 2019 and March 2022 (Figure 3).

The evidence to date suggests that the reduced therapy minutes has not worsened patient outcomes. While implementation of PDPM has been associated with a drop in therapy minutes in the range of 13% to 19%, this has not been associated with changes in length of SNF stay, functional status at SNF discharge, rates of discharge to the community, or readmission to the SNF13 or the hospital.14

Although the PDPM was intended to be budget-neutral, CMS’ initial analysis showed an increase in payments of about 5%, or $1.7 billion per year. As a result, CMS is phasing in a 2.3% reduction in SNF payment rates in both FY 2023 and FY 2024.15

In another attempt to improve the value of SNF services, CMS launched a value-based payment (VBP) for SNFs in October 2018. Designed to be budget-neutral, the program sets aside 2% from the Medicare Part A funding pool, and rewards or penalizes SNFs based on their risk-adjusted 30-day hospital readmission rates.16 In the first two years of the program (FYs 2019 and 2020), only 26% and 19% of facilities earned positive incentives, whereas 72% and 69% of facilities earned negative incentives.17 There is some evidence that VBP penalized poorly performing facilities, those with large populations of frail older adults, and those with many socially vulnerable patients (racial/ethnic minorities, lower socioeconomic status).18 Furthermore, although SNFs can receive rewards for improving their performance, few low-performing facilities were able to improve their readmission rates enough to avoid a financial penalty, raising concerns that the VBP program did not offer a viable path for low-performing SNFs to avoid financial penalties.19

For FY 2024, CMS has proposed changing the structure of its VBP plan.15 These changes include focusing on preventable readmission, rather than all-cause readmission; supplementing the readmission metric with four new quality metrics including nursing turnover and functional status at SNF discharge; and introducing a health equity adjustment, which rewards SNFs for taking on higher-risk populations (defined as at least 20% dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid).

Most Medicare beneficiaries are now receiving SNF care through plans or organizations that differ from the fee-for-service model used by traditional Medicare. In general, these alternative payment mechanisms use financial incentives to reward providers for efficiency and effectiveness, rather than paying for the volume or intensity of services. By holding providers accountable for the costs and quality of care, these mechanisms are designed to increase the value of the Medicare dollar spent on PAC.

More than 50% of Medicare beneficiaries are now covered by MA, in which health plans are paid a monthly capitated rate to cover all medically necessary services for their members, including PAC. MA plans contract with preferred PAC providers using negotiated rates. They can restrict the choice of PAC providers and use a variety of utilization management strategies to control costs, including patient copayments and prior authorizations. MedPAC estimates that MA plans pay SNFs per-diem rates that are 25% less than traditional Medicare.2 Perhaps not surprisingly, MA patients are more likely to be admitted to lower-quality SNFs than their fee-for-service counterparts.20

The evidence on MA’s impact on SNF use and outcomes is largely positive. Compared to patients enrolled in traditional Medicare, those enrolled in MA are less likely to be admitted to a SNF after hospital discharge and have shorter SNF stays and lower rehospitalization rates after a SNF stay, although the effects of MA enrollment on mortality are mixed.21-23

There is also evidence that MA payment strategies can spill over to traditional Medicare. For example, in markets with high MA enrollment, traditional Medicare enrollees are less likely to be admitted to a SNF after hospital discharge24 and, when they are admitted, they have shorter SNF stays.12 Similarly, when the PDPM payment model was implemented in traditional Medicare, therapy minutes for MA enrollees in SNFs also declined.25

I-SNPs are specialized MA plans for long-term nursing home residents, almost all of whom are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. I-SNPs are one example of a larger group of special needs plans that focus on aligning incentives and improving the care of dual-eligible beneficiaries by integrating Medicaid and Medicare services. Like other MA plans, I-SNPs replace traditional Medicare with a capitated managed care model. Like some other MA plans, I-SNPs enrollees are not subject to the 3-day rule to initiate a SNF stay, nor are they obligated to mandatory patient cost sharing at day 21 of a SNF stay. Unique to an I-SNP, this capitated model holds nursing homes accountable for residents’ Medicare spending. Together, this establishes incentives for nursing homes to reduce unnecessary spending and to invest in capabilities to provide higher acuity clinical care onsite rather than transferring the patient to a hospital. I-SNPs rely upon advanced practice clinicians (such as nurse practitioners) to coordinate care, with the goal of reducing costs and improving outcomes by preventing unnecessary emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization. I-SNPs thus align nursing homes’ financial interests with Medicare’s push to increase the value of its spending.

The number of I-SNPs is small but growing, with 192 plans now covering 112,000 beneficiaries.26 The evidence of its effects is limited but promising, with I-SNP beneficiaries having fewer hospitalizations, ED visits, and rehospitalizations, but a much higher rate of SNF use. This combination could result in significant cost reductions from lower rates of preventable hospitalizations and ED visits,27 suggesting the model of using SNFs rather than the hospital to manage acutely ill nursing home residents may be a high-value use of SNF care.

For the past decade, CMS has experimented with payment models in traditional Medicare that hold providers accountable for the costs and quality of care, with the goal of shifting away from paying for the volume of services and toward paying for the value of these services. Many APMs target the use of PAC, which is commonly seen as a source of low-value spending for Medicare.

In general, APMs can be divided into two types: those that hold providers accountable for the total cost of an episode of care (for example, bundled payment models) and those that hold providers accountable for the total costs of care for a specific population (for example, accountable care organizations [ACOs]). In many bundled payment models, providers are responsible for the hospital and post-hospital costs of a single episode of care, such as a surgical procedure. In population-based payment models, provider reimbursement is tied to the costs and quality of all health care services provided to a given patient over the course of a year.

The Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) was Medicare’s first mandatory bundled payment demonstration. Participating hospitals were accountable for the hospital and 90-day post-hospital costs of patients undergoing hip, knee, or ankle replacement. The evidence suggests that CJR reduced spending, primarily through reductions in institutional PAC, with little impact on outcomes.28,29 The demonstration runs through 2024.

Another large experiment with bundled payment in traditional Medicare is the voluntary Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative (BPCI). Between 2013 and 2018, two BPCI models (called model 2 and model 3) included PAC spending in the targeted episode of care.30 In model 2, participating hospitals or physician groups received one bundled payment for a specified surgical or medical condition, which included an inpatient stay and all related services (including PAC) for 90 days after hospital discharge. In contrast, model 3 participants were PAC providers (mostly SNFs) that assumed responsibility for the costs of all post-hospital care, including PAC, readmissions, emergency care, and outpatient visits, starting on the day of admission to the PAC facility and continuing for 30, 60, or 90 days.

The evidence on BPCI model 2 is encouraging, with evaluations finding reductions in total episode spending with no changes in mortality rates for most episodes.31,32 The spending reductions were largely driven by reduced spending on institutional PAC.

The evidence from BPCI model 3 is less encouraging. In a study limited to patients undergoing lower extremity joint replacement, the model was associated with decreased Medicare spending related to a decrease in average length of SNF stay.33 But a larger study of all conditions in BPCI found no changes in spending or patient outcomes associated with the model, and concerning decreases in spending on frail patients.34 A five-year evaluation found that few SNFs participated in this voluntary model, and that 45% of them withdrew by the end of the initiative.35

In October 2018, CMS replaced the BPCI demonstration with BPCI-Advanced, a nationwide voluntary program with stricter participation rules, in which an episode can begin with an inpatient admission or outpatient procedure. Early data among a limited set of participants shows continued decreased SNF utilization and decreased readmission rates across several conditions.36

An ACO is a group of clinicians, hospitals, and other health care providers that agree to work together to coordinate care for attributed patients across settings and providers and to be held accountable for total costs and quality of care provided. In most ACOs, providers share in the savings (or costs) of care below (or above) a benchmark for spending. The Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) is Medicare’s largest ACO program.37

ACOs reduce Medicare spending on PAC, although the size of the effect is modest. The reduced spending results from both decreased SNF utilization and shorter stays in SNFs.38,39 There is some evidence of spillover as well, with lower readmission rates, shorter SNF stays, and less Medicare spending on SNFs for all Medicare beneficiaries in hospitals and SNFs that participate in ACOs.40

The combination of bundled payments and ACOs appears to be synergistic. Readmission rates for medical and surgical episodes and PAC spending on medical episodes are lower for patients both assigned to an ACO and hospitalized under a bundled payment program.41

Alternative payment models and population-based capitation have shown great promise for increasing the value of the Medicare dollar spent on PAC in nursing homes. By aligning incentives across settings and providers, these payment strategies have reduced SNF use and spending without significant changes in patient outcomes. In contrast, recent changes in how traditional Medicare pays SNFs have not led to cost reductions nor quality improvements, even though payment changes were designed to increase the value of services provided.

We recommend that CMS expand the use of APMs and managed care arrangements that reward PAC providers for value, not volume. The prevailing evidence shows that value-based payment strategies can reduce the growth of SNF spending and improve outcomes. It suggests that financial incentives should be aligned across services and provider types, with the most promising strategies being those that encourage institutional investment and change. Holding entities accountable for the entire costs of care, whether it is done at an episode or population-based level, can help overcome conflicting incentives and silos of care. I-SNPs hold great promise as a funding mechanism for nursing homes, because they can reward nursing homes for providing and coordinating a full range of acute and post- acute care for their residents.

Further, we recommend that policymakers reconsider payment rules in traditional Medicare that have outlived their usefulness and may be driving inequities and inconsistencies in SNF care. In particular, we recommend that policymakers remove the 3-day hospital stay requirement for SNF coverage. Many Medicare Advantage plans and ACOs have managed to reduce SNF spending while opting out of the rule. When the rule was waived during the pandemic, the change did not appreciably increase SNF spending, and may have reduced unnecessary hospitalizations. Further, we recommend that policymakers eliminate the substantial patient copayment at day 21 of a SNF stay. On the one hand, the copayment policy harms more vulnerable patients, racial/ethnic minorities, and those who live in poorer areas. On the other, the policy incentivizes SNFs to extend stays due to the generous per-diem rates and full coverage up to day 21. Instead, we suggest policymakers consider more modest copayments that do not kick in at an arbitrary point in a SNF stay.

If Federal Support Falls, States May Slash Home- and Community-Based Services — Pushing Vulnerable Americans Into Nursing Homes They Don’t Want or Need

Men are Stepping Up at Home, but Caregiving Still Falls On Women and People of Color LDI Fellow Says

Economist Norma Coe’s Caregiving For Relatives Informed Her Research

The Decline Since 2020 May Signal Gaps in Service and Access

Penn Event Explores the Limits of Chronological Aging and Related Issues

LDI Executive Director Discusses New Findings on Medicare Beneficiaries’ Use of Home Health