NIH on the Brink: How to Fund Medical Breakthroughs in the Trump–Kennedy Era

With Drastic Cuts on the Table, What’s the Best Way To Fund Medical Innovation – NIH Grants, Prizes, or Bold New Models?

Health Equity | Population Health

News | Video

Climate change disasters’ impact on population health, health disparities, and the national health care delivery infrastructure are subjects of too little academic research at a time when policymakers’ need for such data has never been greater. That’s according to five top academic research experts convened in a virtual seminar at the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI).

Moderator and LDI Senior Fellow Courtney Boen, PhD, MPH, opened the March 24 “Climate Change, Disruption, and Health Equity” session by noting that the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified climate change as “the biggest threat to health in the 21st century.”

“Diseases, food and water insecurity, undernutrition, and forced displacements are some of the indirect impacts that follow many of these climate catastrophes and add up to massive effects on health,” said Boen, an Assistant Professor at Penn’s School of Arts and Sciences.

Individual climate disaster events often obliterate much of the physical infrastructure of communities as well as the health care systems that serve them at a time when the residents are suffering catastrophic levels of emergency health care needs. At the same time, the community trauma generated by these experiences produces the kinds of emotional and physical stressors well known to have serious short- and long-term negative health impacts. But, as demonstrated in events such as Hurricane Katrina or the COVID-19 pandemic, government health agencies and the health care delivery system have for decades failed to be prepared, staffed, or adequately supplied to effectively deal with such massive health emergencies.

Boen, whose research focuses on how population health is affected by structural racism and other social determinants, pointed out that the degree to which an individual is impacted by climate disasters is shaped by the forces of structural inequities and economic exploitation. Much the same as in a pandemic, the people who tend to fare the worst in climate disasters are those in under-resourced communities with low levels of resiliency and often even lower levels of priority in governmental response and recovery efforts.

“My own field—sociology—is centered on inequity, but climate-related research takes up only a small space in it,” said Boen. “The growing frequency and intensity of climate disasters and subsequent impact on health and health inequities requires that we focus more on the gaps in science that currently exist.”

Panelist Elizabeth Fussell, PhD, Professor of Population Studies and Environment and Society at Brown University noted that, “What’s so challenging in this climate emergency is that risk communication has been muddied by climate misinformation that, in the U.S., has been almost stronger than the accurate risk communication based on science. To address inequality, we need to better understand how people receive and process information and what gets in the way of their translating information into behavior change and adaptation. That is a challenge that I think sociologists need to take more seriously.”

According to panelist Sue Anne Bell, PhD, FNP-BC, another important focus of new research should be on comprehensively measuring the preparedness and resilience levels of communities across the country. Essentially the issue is one defined by the traditional science adage that you can’t improve what you can’t measure.

“We should think of resilient systems as a continuum of how we mitigate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters,” said Bell, an Assistant Professor of Systems, Populations, and Leadership at the University of Michigan School of Nursing. “Resilience metrics can guide our progress and show us what the gaps are in those areas. There are many different metrics in use and under development around resilience and resilient health today, but we don’t have a metrics system that encompasses the total picture of what a resilient system is. We need to develop an integrated data platform that also includes harmonization across these metrics.”

In 2012, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Committee on Increasing National Resilience to Hazards and Disasters issued the 260-page report, “Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative.” It emphasized the critical importance of creating and maintaining a coherent national system of resilience building and disaster readiness. It concluded, “The costs of disasters are increasing as a function of more people and structures in harm’s way as well as the effects of the extreme events themselves. … The nation needs to build the capacity to become resilient, and we need to do this now.”

Eleven years later, that has still not happened, even as climate disasters of unprecedented size and frequency continue to rage across the continent.

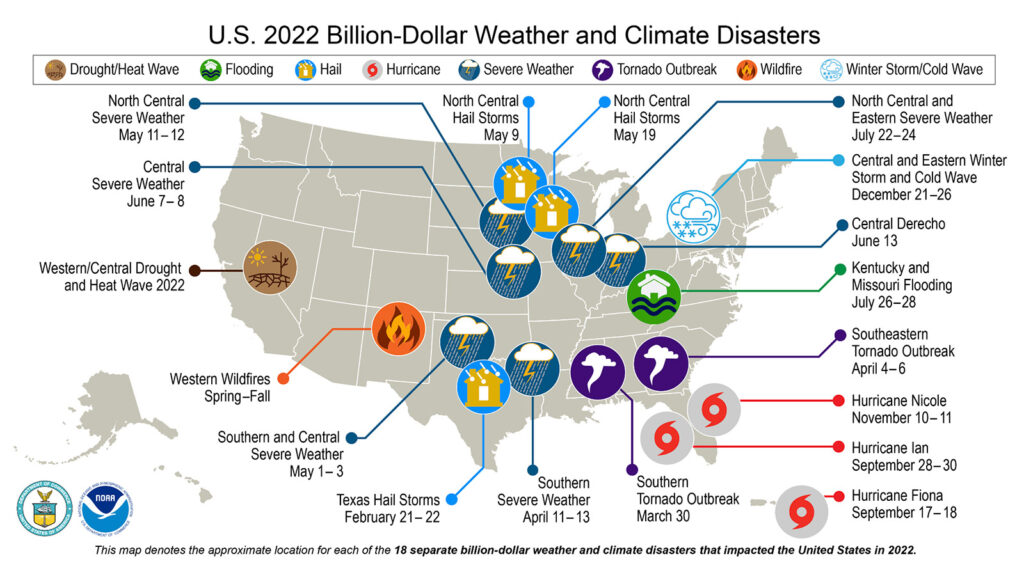

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), from 1980 through 2022, an average of eight U.S. catastrophic climate disasters occurred annually. But the average for the five most recent years up to 2022 is 18—or more than twice as many community-crushing disaster events.

Overall, storm-driven flooding across the country has increased by 50% from 2010 to 2020. Based on flood insurance claims, NOAA reports that over 1.2 million U.S. buildings were destroyed by flooding during the same decade. Because that only includes buildings that were insured, the actual total number of destroyed buildings could be as much as double that amount.

Deadly extreme heat disasters have become commonplace. During the last three years, 46 states have experienced 100-degree temperatures and the average number of 100-degree days in a row increased. Scientists agree this trend will continue upward.

“Heat is the number one killer when it comes to weather conditions and there is a social justice and inequality component in this,” said panelist Michael Mann, PhD, Director of the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability, and the Media. “Urban heat islands are hotter than outlying areas and many of the underserved communities are located in these areas. We’re starting to see levels of heat in these areas that are dangerous enough that human beings can’t spend much time outside without succumbing to heat stress.”

“Urban heat islands are not an accident,” said panelist Sacoby Wilson, PhD, MS, Director of Community Engagement, Environmental Justice, and Health at the University of Maryland College Park School of Public Health. “In many cases, structured racism is the reason why you see a lot of communities of color experiencing differential burdens of exposure and risk from climate change. They don’t have access to the infrastructure that allows them to be resilient to these climate-related perturbations that create conditions of climate redlining. This is about the haves and have-nots. The haves have more resilient infrastructure and the have nots have less resilient infrastructure because of disinvestments that lead to the exacerbation of underlying risk.”

Fussell pointed out that despite the Biden Administration’s efforts to provide heat wave relief in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, there is structural inequality built into that legislation.

Among its provisions, the law provides $391 billion in funding aimed at combating climate change and its health effects through measures including financial incentives for construction companies and homeowners to convert to high-efficiency electrical heat pumps for more powerful space cooling and heating.

“We’ve been talking about the lethal hazard of extreme heat and this law directly addresses that risk by putting more efficient cooling systems into people’s homes,” said Fussell. “But to take advantage of those incentives, you have to be a homeowner and have the up-front money to actually buy those systems. A lot of the population that rents their homes tend to be of lower income and members and racialized groups that have fewer resources. There’s no plan for how those people can access more efficient, sustainable cooling systems. To achieve that would mean giving incentives to their landlords to make those investments in rental housing. That’s the problem we have to overcome to figure out how to serve these populations that are more likely to live in a heat island and face a higher level of risk for this climate-driven health hazard.”

The panelists discussed how to get more of the flows of federal climate change mitigation money into underserved communities, as well as of the inevitable politics and intense lobbying involved in any aspect of the climate change policy debates at the federal and state government levels. They agreed that one of the biggest barriers to advancing climate change preparedness, mitigation, and resilience programs is the massive waves of misinformation and disinformation being used to obscure full public understanding of the global warming crisis.

“This communications battle is taking place right now in an adverse environment where we face a very stiff headwind of a concerted misinformation campaign,” said Mann. “That’s why it isn’t enough for researchers to just publish the science and hope that if we get it out there, politicians will make policy based on good science. There’s a major effort underway to make sure that that doesn’t happen.”

“Critics love to claim that our climate models exaggerate the problem and that our predictions have somehow failed,” continued Mann. “But if you look at the predictions that were made decades ago, we’ve done a very good job of predicting the warming that was expected from carbon pollution in the atmosphere. Our models actually underestimated some of these critical impacts. That’s really important to understand from a risk standpoint because, going forward, the situation will be worse than our models predicted.”

With Drastic Cuts on the Table, What’s the Best Way To Fund Medical Innovation – NIH Grants, Prizes, or Bold New Models?

An Analysis of Penn Medicine Healthy Heart Program Provides Insights

From 1990 to 2019, Black Life Expectancy Rose Most in Major Metros and the Northeast—but Gains Stalled or Reversed in Rural Areas and the Midwest, Especially for Younger Adults.

Findings Suggest That Improving Post-Acute Care Means Looking Beyond Caseloads to Nursing Home Quality

They Reduce Coverage, Not Costs, History Shows. Smarter Incentives Would Encourage the Private Sector

The 2018 MISSION Act Cut Travel Times for Veterans Needing Major Heart Procedures but That Came With More Complications in VA Community Care