Health Equity | Population Health

News

Penn Community Health Care Worker Program Expands Beyond Penn

Goes From Student Shreya Kangovi's Research Project to National Business in Seven Years

The widely publicized University of Pennsylvania’s “IMPaCT Community Health Workers” concept that began seven years ago as Shreya Kangovi’s student research project and worked so well it was adopted by Penn’s Health System, is now reorganizing itself as a national business.

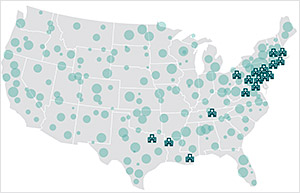

In a presentation at the Penn Medicine’s 2018 Innovation Accelerator Pitch Day (above), Penn Center for Community Health Workers (PCCHW) Chief Operating Officer Jill Feldstein outlined how the Center and its branded intellectual property core, the Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets (IMPaCT), is now selling services, tools and technology products to twenty health care institutions from Maine to Texas.

PCCHW is also ramping up marketing efforts to expand across the rest of the country with programs that include a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval-like IMPaCT branding for client institutions.

Verification

“We want to be able to verify that our clients’ community health workers and supervisors and the program itself are using evidence-based best practices to materially improve health outcomes and the care experience for the most vulnerable patients,” Feldstein said.

Feldstein, who joined PCCHW four years ago, earned her masters degree in public affairs at Princeton and received her degree in economics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She estimated that the IMPaCT intervention has touched more than 7,000 patients at Penn and, in its first round of external marketing operations, tens of thousands of others.

IMPaCT is an evidence-based health care delivery system that is the result of several years of intensive research work by Penn Medicine Assistant Professor and LDI Senior Fellow Shreya Kangovi, MD, MSHP. She began the project seven years ago as her Penn-RWJF Clinical Scholar thesis.

The IMPaCT intervention hires, trains and manages teams of people from low-income communities like West Philadelphia to function as health system navigators for high-risk members of their own communities.

Randomized controlled trials

Several years of randomized controlled trials show the IMPaCT system significantly improves metrics of health care quality and cost, including the systematic lowering of readmissions rates, increased access to primary care and the increased effectiveness of discharge communications and procedures.

The national commercialization of IMPaCT is a major milestone for both Kangovi and the six-year-old Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation (CHCI) that selected her project as one of its first “Innovation Accelerator” efforts. The two teams have worked hand-in-hand ever since.

“This defines my career,” Kangovi said. “It’s what I expect to be doing for the rest of it. I love my job and the team I work with. We spent the first couple of years testing this and getting IMPaCT to work and now that it does, I have to get it out there or else I will have failed the community health care workers and the millions of patients they could be helping.”

Scale and high quality

“I am very idealistic,” Kangovi continued, “but I think business approaches are a really good way to scale a high quality health care delivery product and do so with consistency.”

The Innovation Accelerator and its annual Pitch Day competition are flagship CHCI programs offering individuals or teams of physicians, nurses and other staff members the opportunity to test ideas for improving health care delivery. Ideas that show promise in short term proof-of-concept tests are funded for further testing and development. IMPaCT was highlighted at this year’s Pitch Day not as a competitor but rather as a graduate and example as one the most successful projects nurtured by the CHCI since it was launched by former LDI Executive Director David Asch*, MD, MBA, in 2012.

“In terms of novel care delivery models, Shreya’s evidence-based intervention is the farthest along of those we’ve helped incubate,” said CHCI Chief Innovation Officer Roy Rosin, MBA. “She has demonstrated success in the science and practical applicability of her model and now, other national health care organizations see IMPaCT’s ability to drive higher value, hear that this approach to helping vulnerable populations not only makes them better off but drives a $2 return for every $1 invested, and are showing a willingness to pay for the improved outcomes.”

Achieving measurable impact

“You have to achieve scale if you want to have measurable impact with a health care innovation,” said Rosin. “From the very beginning, one of the Center’s goal has been to support the development of interventions that materially improve the outcomes and experiences of patients. Another goal was to help identify business models that allow these new interventions to be financially viable, thus enabling scale.”

“It’s very important to understand the Innovation Center’s own model,” continued Rosin, who is also an LDI Senior Fellow. “We are often not the innovators. We are here to support and enable the efforts of Penn Medicine’s innovators. In the case of Shreya, she had all the care delivery and patient insights. She is a remarkable innovator in her own right and a natural entrepreneur.”

Rosin, who joined Penn and the new Innovation Center in 2012, also became an Associate Director of the RWJF Clinical Scholars program and Kangovi was one of the first students he met. “She was working in a very iterative manner similar to what you see in successful startup founders,” he said. “She was determined to achieve better clinical outcomes and she’s now achieved them, particularly chronic disease outcomes, better engagement outcomes in terms of how the patients interact with the health system and better economics for both the health system, payers and, frankly, for society when you’re seeing the reduction in readmissions Shreya’s model achieves.”

Venture capitalist similarity

The operational construct of CHCI is similar to that of a venture capitalist. Once it identifies promising research projects, it “wraps” them in the infrastructure needed to support and nurture testing and development efforts. The matrix of services it provided to the IMPaCT project included organization and management consulting, personnel recruitment, connections to prospective customers, marketing and communications strategy guidance, the design, launch and maintenance of a marketing website, design and production of educational, training and marketing materials, and technical expertise to help with software vendor selection.

Kangovi was born in Bangalore, India, and came to the U.S. as a three-year-old when her parents immigrated here. She notes that her research decision to explore the use of non-professionals from low-income neighborhoods as medical system navigators “was not a genius idea moment,” and originated when she was visiting her native country.

Tiffen Wallahs

In the early 2000s when she was a medical student at Harvard, Kangovi traveled through India and encountered “Tiffin Wallahs.” The term roughly translates to “lunch box delivery man” and these workers have been a staple of the local food service industry since the time of the British Raj. Tiffin boxes are sturdy, metal pot-shaped containers used to transport freshly-cooked hot meals. It is common, for instance, for wives to cook meals in in mid-morning, pack them in Tiffen boxes and have them delivered to their husbands at work by a neighborhood Tiffen Wallah who also returns the lunch box later that same day.

Tiffin Wallahs go about their daily task of delivering lunch boxes throughout India’s cities.

In business magazines Kangovi read about the surprising findings of case studies whose authors marveled at how well organized the decentralized networks of low-income, poorly educated Tiffin Wallahs were as they transported these metal boxes back and forth across sprawling sections of the subcontinent’s largest cities each day.

“It was an amazing fact,” said Kangovi, “that this largely illiterate workforce had achieved Six Sigma efficiency in its own organic way. They were crushing this complicated task with such exact management and execution of a very complex daily process in an often chaotic and unpredictable environment. It was really impressive.”

Not long after, Kangovi briefly worked at the Lala Ram Swarup Institute of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Hospital in New Delhi, where community health workers were an integral part of the care delivery system.

‘The Tiffin Wallahs of health care’

“That’s where I saw them in action and became familiar with the idea of community health workers,” she said. “And it’s also where I realized that they were the Tiffin Wallahs of health care. That was something that stuck in the back of my mind after that. When I got to Penn Medicine in 2006 for my residency, internship and clinical training, I’d see all these patients coming in and getting $12,000 MRIs and we were titrating every milligram of their blood pressure medicines and then sending them back out to live in the streets and struggle with all these other unaddressed socioeconomic issues that affected their health.”

“I could also see that West Philadelphia had a lot of residents who were really good and really smart and were already helping one another out in their community but were overlooked by health care system because they didn’t have a bunch of letters behind their name,” Kangovi said.

“When I started my project, I had fantastic support from my mentors, Judith Long** and David Grande***, but there was definitely skepticism elsewhere with some providers asking ‘you’re really going to bring in people who are not nurses or case managers or social workers and try to make them part of the professional health care delivery system?”

“But later,” Kangovi continued, “I got to see some of the same providers who had been skeptical but now NEEDED community health workers that we specifically hired based on their innate qualities of empathy, altruism and reliability.”

“It was a really beautiful moment,” Kangovi said, “and one of those times when you realize how much your research can really mean — to yourself as well as a whole lot of other people at Penn and around the country.”

~ ~ ~

* David Asch, MD, MBA, is the Executive Director of the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation and an LDI Senior Fellow.

** Judith Long, MD, is a Professor of Medicine at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, Chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine, and an LDI Senior Fellow.

*** David Grande, MD, MPA, is an Associate Professor of Medicine at Perelman and Director of Policy at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI).