Blog Post

Phosphorus Control for Dialysis Patients

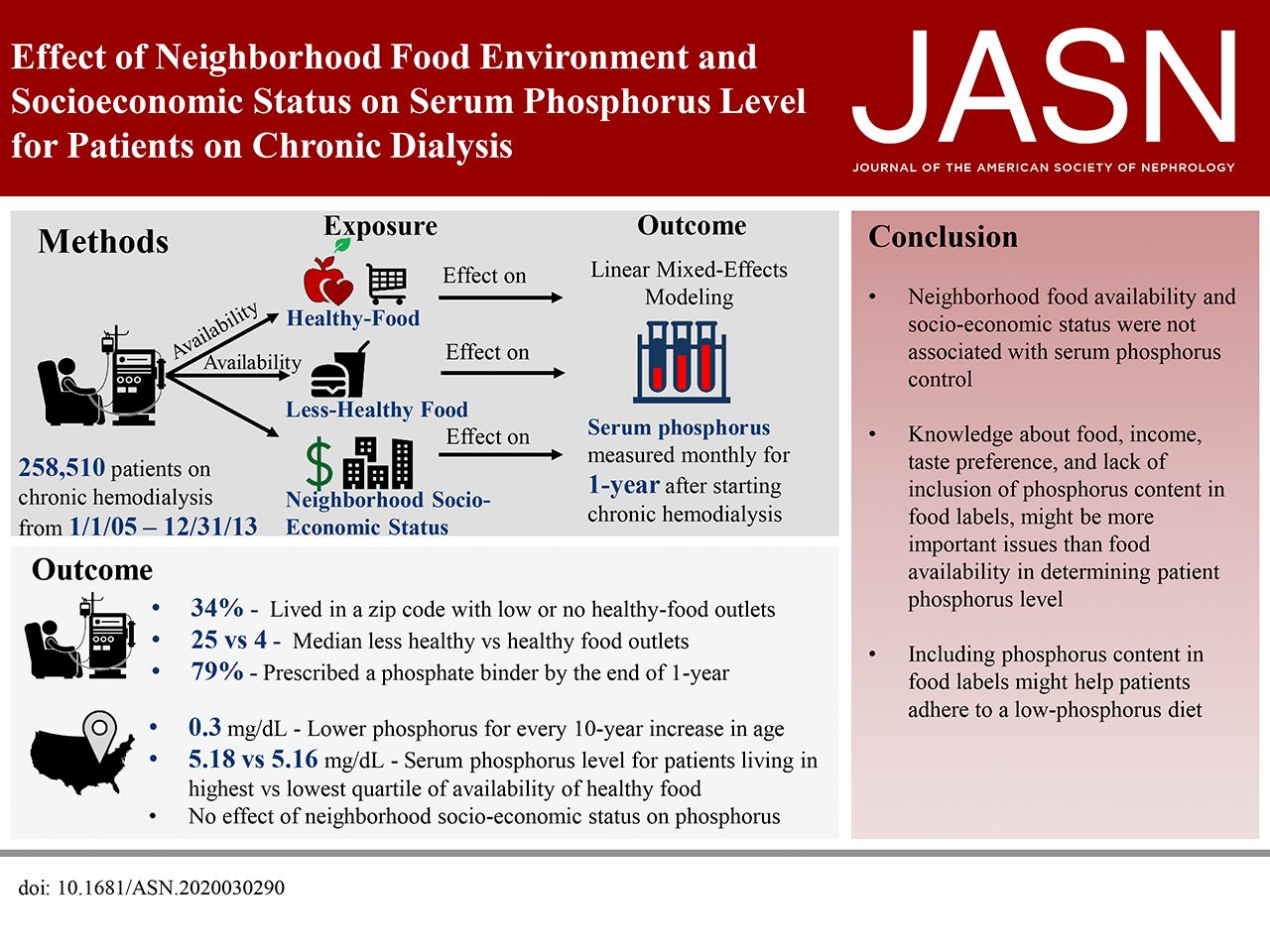

Food Environment, Socioeconomic Status Not Linked To Phosphorous Level

About one third of chronic dialysis patients have persistently high blood phosphorus levels, which increases risk for vascular damage, cardiovascular disease, and death. Some patients can control phosphorus levels through a healthy diet, although many also require the use of pills that remove dietary phosphorus in the gut. But what about patients with limited access to healthy food outlets? In a recent study, we found no link between better access to healthy food and lower blood phosphorus level, suggesting that other factors—such as patients’ food literacy, ability to read food labels, and food preferences—may play a larger role in achieving phosphorus control.

We linked national data on nearly 260,000 chronic dialysis patients to data from the US Census Bureau and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the number of “healthy” (e.g., supermarket) and “less healthy” (e.g., fast food restaurant) food outlets in the neighborhoods surrounding patients’ homes and their dialysis units. Dialysis patients have phosphorus measured in their blood every month. Because many unhealthy processed foods have added phosphorus, we compared monthly phosphorus levels in patients in “healthy” neighborhoods with those in “less healthy” neighborhoods.

The median age of beginning dialysis in these patients was 64 years. Consistent with national patterns of kidney disease, nearly half of our sample identified as Black (32%) or Hispanic (15%). Patients generally had access to a much higher number of “less-healthy” food outlets (25) compared to “healthy” food outlets (4). However, living in a neighborhood with better availability of healthy food was not associated with a lower phosphorus level. The average serum phosphorus level in the top 25% of neighborhoods with the “highest availability” of healthy food was 5.18 mg/dL, compared to 5.16 mg/dL in the bottom 25% of neighborhoods – a tiny difference. Surprisingly, median neighborhood income was also not associated with differences in blood phosphorous levels.

The academic literature and mainstream media have popularized the idea of “food deserts,” where there are no supermarkets. But our results show that most dialysis patients live in areas with multiple healthy and unhealthy food outlets (though some patients may need better transportation, shopping assistance from loved ones, or food delivery services to get their shopping done).

At first, our research team struggled to understand these results. However, there are a number of plausible explanations. Our group believes that individual food preferences, poor food labels that do not indicate the amount of phosphorus, poor health literacy, and patients’ overall difficulty in adhering to a strict dialysis diet likely play a role in controlling phosphorus. Eating habits are a highly complicated issue that is often oversimplified and overlooked in discussions about healthy food access. Notably, it is extremely difficult for patients to maintain a healthy and low phosphorus diet if they usually eat food prepared by others (i.e., purchased at a restaurant or from a grocery store). Many Americans also enjoy the taste and convenience of processed foods, which are heavily marketed.

Our research suggests that changing the American diet—particularly for those with chronic illnesses—will be a difficult and complex process. While improving access to healthy and affordable food should be a priority for policymakers and public health advocates, it must be paired with persuasive education and marketing efforts to be successful. Policymakers, providers, and advocates should focus on educating the American public about healthy food options to improve health literacy and change food preferences. Broad education and marketing campaigns could shift people’s focus away from processed foods and give them the confidence to prepare simple, healthy meals at home. Finally, these efforts should be combined with improved food labels that enable consumers to make healthier choices. These changes could make a tremendous difference to the health of the nearly half a million Americans who suffer the burdens of chronic dialysis.

The study, Effect of Neighborhood Food Environment and Socioeconomic Status on Serum Phosphorus Level for Patients on Chronic Dialysis, was published in JASN in October 2020. Authors include Vishnu S. Potluri, Deirdre Sawinski, Vicky Tam, Justine Shults, Jordana B. Cohen, Douglas J. Wiebe, Siddharth P. Shah, Jeffrey S. Berns and Peter P. Reese.