Acupuncture Could Fix America’s Chronic Pain Crisis–So Why Can’t Patients Get It?

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

In Their Own Words

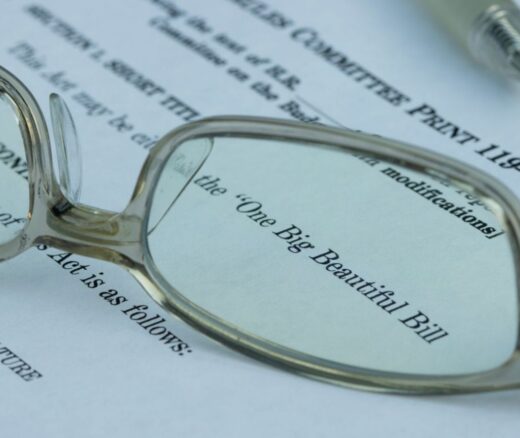

In the early hours of May 22, the Republican-controlled House passed its plan to advance the party’s fiscal agenda. A YouGov poll out days before found that just 36% of Americans supported the bill, and research indicates that the plan is unlikely to gain in popularity as the extent of its cuts becomes clear.

That plan includes hundreds of billions of dollars in cuts to Medicaid, the government-funded health insurance program targeting low-income Americans that insured 71 million people as of December 2024. Though the final GOP proposal stopped short of the most far-ranging Medicaid cuts under discussion, the proposed cuts are still sweeping and would amount to the largest cuts in the program’s 60-year history. In fact, they are estimated to reduce Medicaid spending by $625 billion and lead some 10.3 million people to lose their health insurance through Medicaid alone, with additional losses due to the end of expanded ACA insurance credits.

But to become law, the proposal also needs to pass the Senate and be signed by President Trump. And there are continued signs that such large cuts to Medicaid may not fly in the upper chamber. U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican, argued in The New York Times that “slashing health insurance for the working poor… is both morally wrong and politically suicidal.”

The evidence from my book, Stable Condition, on the politics of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA, a.k.a. Obamacare), suggests that Hawley is right to worry about the political costs of large Medicaid cuts. Medicaid is quite popular, and as it has grown to cover more people, its support has grown more bipartisan.

In a January 2025 KFF Health Tracking poll, 88% of Democrats reported favorable views of Medicaid–but so did 64% of Republicans. In fact, voters in such solidly Republican states as Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Idaho opted to expand Medicaid through ballot initiatives.

Not coincidentally, Republicans have also become more reliant on Medicaid. In that same 2025 KFF survey, 51% of Democrats reported that either they or a family member had been covered by Medicaid, a number that was 44% among Republicans.

Stable Condition provides further reason to suspect that unprecedented Medicaid cuts could provoke a backlash. Compared with insurance purchased from private companies on the ACA exchanges, Medicaid is administered directly by government actors. As a result, voters can more easily connect changes in their insurance to the politicians who produced them. When states opted to expand Medicaid, their low-income residents became more supportive of the ACA.

The ACA provides lessons about what happens when government actions cost people their health insurance. Specifically, the ACA’s regulatory changes induced the cancellation of millions of health insurance policies in late 2013, and also initially imposed fines on the uninsured.

People react especially negatively when something that they already had is taken away, and the ACA was no different: the insurance cancellations and the individual mandate meant that the types of people who were likely to be uninsured after the ACA’s implementation became more negative towards the law.

One bipartisan strategy for passing legislation that imposes costs on citizens is to do so indirectly to deflect blame. In this case, the legislation forces states into the role of “bad cop” by giving them strong incentives to make cuts or pay more for existing programs. For example, states that use their own money to cover unauthorized immigrants will receive a lower matching rate for other residents covered through the Medicaid expansion. The proposal also imposes other costs on states, such as requiring that they contribute 5% of families’ Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP or food stamps) allotments and shouldering more of the burden of the program’s administration.

Another way this bill forces states into the role of “bad cop” is through new requirements–administered by the states–that would mandate adult Medicaid recipients work if they are without children or not disabled. In part, this requirement would make it harder to access benefits even for the majority of adults on Medicaid who are already working by heightening the program’s administrative burdens.

On its own, the idea of work requirements wins meaningful support from Americans, with 49% supportive and 32% opposed in a June-July 2023 survey we conducted via NORC. Unsurprisingly, this proposal is more popular with Republicans than Democrats–in a YouGov survey of political activists administered between December 2024 and January 2025, we found that 68% of Republican activists supported work requirements while just 42% of Democrats did.

In part, public opinion on the Republicans’ fiscal plans overall will depend on whether its more popular aspects–including work requirements and some of the tax cuts–are as clear to citizens as its cuts to Medicaid.

That said, one very common pattern in public opinion is what’s known as “thermostatic response”: as elected officials move policy in one direction, the public adjusts like a thermostat, shifting in the opposite direction. Public opinion towards the ACA was stable for years, until moves by Trump and Congressional Republicans in 2017 to repeal the ACA pushed public opinion to become meaningfully more supportive of the law. In fact, the Republican leader in the House at the time, Kevin McCarthy, blamed the 2017 ACA repeal push for the Republicans losing control of the House in the 2018 midterm elections.

Given that Medicaid is popular and that it insures more than 70 million Americans, Josh Hawley is right. There’s every indication that large cuts will produce a meaningful backlash among voters.

Daniel J. Hopkins, PhD is a Senior Fellow at the Leonard David Institute of Health Economics, and a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania, with secondary appointments in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and the Annenberg School for Communication.

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

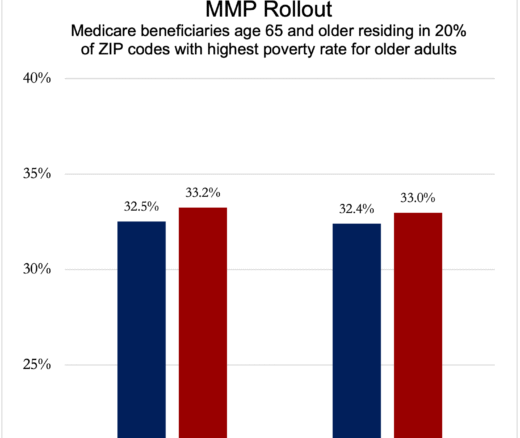

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Research Brief: Shorter Stays in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Less Home Health Didn’t Lead to Worse Outcomes, Pointing to Opportunities for Traditional Medicare

How Threatened Reproductive Rights Pushed More Pennsylvanians Toward Sterilization

Abortion Restrictions Can Backfire, Pushing Families to End Pregnancies

They Reduce Coverage, Not Costs, History Shows. Smarter Incentives Would Encourage the Private Sector