Estimated Overdose Deaths Due to the Loss of MOUD in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

Research Memo: Delivered to House Speaker Mike Johnson and Majority Leader John Thune

News | Video

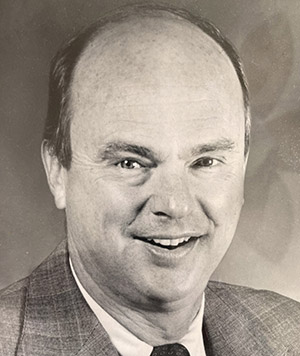

Debunking an often-heard knee-jerk declaration that “the U.S. health care system is the best in world,” LDI Senior Fellow and University of Pennsylvania Vice Provost for Global Initiative Ezekiel Emanuel, MD, PhD, told an audience at an annual Penn lecture series that much of U.S. health care is failing its patients and burning out its clinicians.

Emanuel said U.S. health care is the world leader in achieving five-year breast cancer survival but that that metric was a rare outlier in the country’s overall record of performance across other spheres of care delivery. He also pointed to a recent Gallup Poll that found a majority of Americans rate health care quality as “subpar,” with 21%—a new high in the last two decades—calling it “poor.”

Meanwhile, the costs of the system continued to rise. Currently at $4.7 trillion a year, health care spending is now larger than the gross domestic product (GDP) of both Germany and Japan, Emanuel told the 2024 LDI Charles C. Leighton, MD, Memorial Lecture in the Wharton School’s Huntsman Hall.

In the population health areas of hypertension and diabetes preventive care and treatment Emanuel said, “we are doing a miserable job in diseases that are not that complicated.” He went on to paint a vivid picture of why the U.S. health care system needs to make dramatic changes in its organization and operation.

Emanuel, an LDI Senior Fellow and Co-Director of the Penn Healthcare Transformation Institute, is also the Special Advisor to the Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO). He served as a Special Advisor for Health Policy in the White House from 2009 to 2011, and was one of the architects of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Along with his other accomplishments, Emanuel has written 14 books, the last of which was an analysis of the best and worst health care systems throughout the industrialized world. His Leighton Lecture presentation was focused on the research he is currently doing for his soon-to-be 15th book, currently titled “Creative Rejuvenation: New Lens for Transforming American Health Care.”

Much of his presentation made the case for why dramatic changes are needed across the fragmented and enormously complicated U.S. health care delivery system:

A major impediment to care efficiency and cost control over the last 80 years has been the creation of ten separate systems to provide health care, each in their own unique and ever more complicated way: Employer insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance program (CHIP), Veterans Affairs (VA) coverage, TRICARE, Indian Health Services, Federal Employee Health Benefits, ACA Exchanges, and ACA Medicaid expansion.

Over the decades, each time a new population group has been targeted for coverage, a brand-new program has been created, greatly increasing the overall complexity and fragmentation of the system. This was done, as opposed to expanding an existing program to include the new group in a system of standardized policies, procedures, and practices in both care delivery and payment.

“I was present at the creation of the Affordable Care Act and the expansion of Medicaid,” Emanuel said. “The eligibility requirements don’t match the income we use. The benefit levels don’t match. Fragmentation and complexity add to the time, effort, and cognitive load required for a person to figure out what they’re eligible for. On average, ACA Exchange customers have 113 plan options to choose from. Average Medicare beneficiaries have 60 different Part D plans. Those of you familiar with behavioral economics know that so many choices lead to paralysis. What happens when you have too many choices? Bad choices.”

“Complexity,” Emanuel continued, “also facilitates system-wide waste and inefficiency. You have multiple prices leading to high administrative costs, leading to lots of effort to comply with all the different requirements. And I would argue that institutionalizing the fragmentation and the complexity also creates and reinforces a structure resistant to any systemic reform.”

Along with snarls of incompatible payment systems, fragmentation and complexity negatively affect quality metrics. “Every insurance company, exchange, and regulatory agency has their own quality metrics. Take Medicare—they are using 788 different quality metrics across 34 programs. You’ve got fragmentation even within a single payer. Now they’re trying to reduce that. It’s going to be a very important effort, but it’s long in coming,” Emanuel said.

“Complying with the different quality metrics adds to administrative costs and inefficiency,” he continued. “I would argue that this also adds to clinician burnout. We’re seeing tons of burnout. In 2023, surveys found that 50% or more of physicians and nurses are burned out. If you look at all the different causes those health professionals rank, number one is the administrative tasks. They have to do more and comply with more things. In fact, American physicians spend at least 50% more time on the electronic health record than Europeans because we’re spending more time doing the billing.”

“So, how do you fix sclerotic systems like this?,” Emanuel asked. “Well, if you’re a business theorist, you say ‘creative destruction.’ It’s the process in the marketplace where innovation makes the old way of doing things obsolete. New producers fundamentally reform the structure of a business process, suppressing and superseding the old ways. Think about automobiles replacing the horse, digital cameras replacing film, personal computers replacing mainframe computer, electronic cars that are inevitably going to replace internal combustion cars. We can have creative destruction in business, but we can’t have creative destruction in social systems like health care, like education, like taxes, or like housing policy. You can’t just level the playing field and then have something replace them. So, I don’t think we can destroy our way to a better health care system.”

“My question,” said Emanuel, “is whether some form of creative rejuvenation could be an alternative way to think about it in health care? Is it possible to enact comprehensive structural changes that remove institution-wide structural defects, replace them with new institutional arrangements that solve persistent problems without destruction, but through some rejuvenation process?”

“Well, look at the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland. They have multiple insurers, but they don’t have our problems. How do they do that? What they have that we don’t is universal coverage. They have a government mandate, standardization of benefits, deductibles, copays, quality metrics, etc. Yes, they’ve got separate payers, but they have lots of standardization that prevents the fragmentation and therefore prevents an element of the complexity.”

“I think universal coverage and standardization is necessary. One of the questions is would that be sufficient here? Would that do it enough? Would that evolve to where we need to go? The answer to the question of what this creative rejuvenation process would look like is the one I’m currently trying to answer in this project we’ve been discussing here today,” said Emanuel.

Research Memo: Delivered to House Speaker Mike Johnson and Majority Leader John Thune

Research Memo: Delivered to House Speaker Mike Johnson and Majority Leader John Thune

Hospitals’ Current Cost Reports are Unreliable and Should be Improved, LDI Fellow Finds

If Federal Support Falls, States May Slash Home- and Community-Based Services — Pushing Vulnerable Americans Into Nursing Homes They Don’t Want or Need

Historic Coverage Loss Could Cause Over 51,000 People to Lose Their Lives Each Year, New Analysis Finds

Cited for “Breaking New Ground” in the Field of Hospital Operations