New Model Predicts Stimulant Overdose Risk Among Medicaid Patients

LDI Fellows Used Medicaid Data to Identify Individuals at Highest Risk for Cocaine- and Methamphetamine-Related Overdoses, Paving the Way for Targeted Prevention

Substance Use Disorder

Blog Post

A new study found that methadone treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) has increased in the U.S., but considerable access gaps remain as only about 25% of individuals with OUD receive medication treatment.

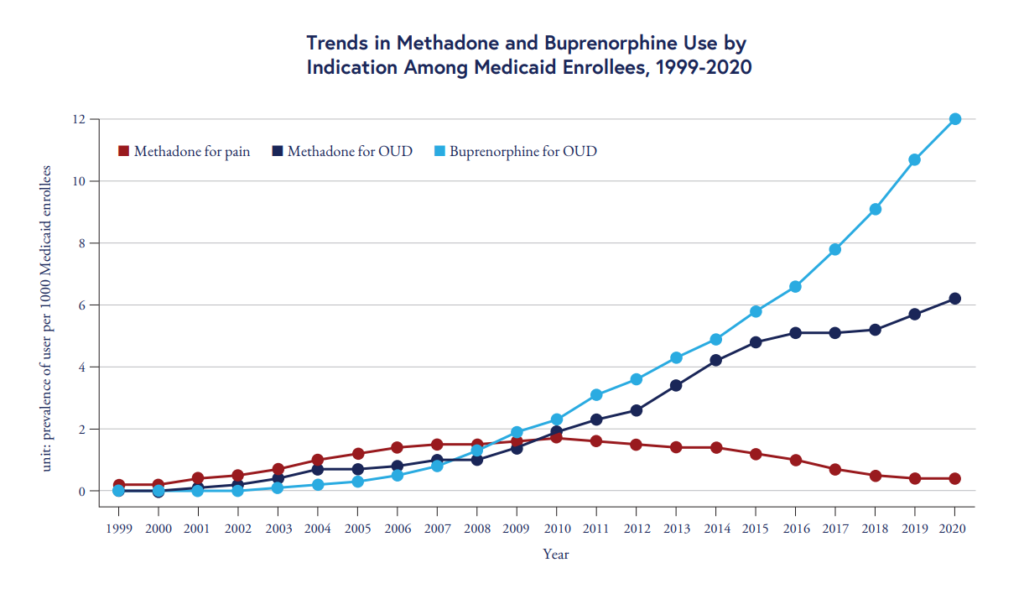

Restrictions around methadone should be eased, say LDI Senior Fellows Ashish Thakrar, Sean Hennessy, Center for Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Therapeutics (CREST) Postdoctoral Researcher Yu-Chia (Sam) Hsu, and colleagues. The medication could help more people. The team quantified methadone use for OUD among Medicaid beneficiaries from 1999 to 2020. Medicaid is the largest insurer of people with opioid use disorder (OUD) in the U.S., covering 47 percent of all nonelderly adults with OUD in 2023.

While methadone use for OUD rose modestly from 1999 to 2010, the team found that use more than tripled among Medicare enrollees after 2010, increasing from 1.9 users per 1,000 enrollees in 2010 to 6.2 users per 1,000 enrollees in 2020.

The chart above also shows that buprenorphine use has outpaced methadone use among Medicaid enrollees. Unlike buprenorphine, which can be prescribed in outpatient settings, access to methadone for OUD is restricted to opioid treatment programs.

Improving methadone access is important, however, as “it is a more attractive treatment option for some patients with opioid addiction who fear the withdrawal that can occur when starting buprenorphine,” said Ashish Thakrar.

Recent policy efforts, such as the Modernizing Opioid Treatment Access Act, introduced in both chambers of Congress in March 2023, have sought to increase access to methadone for OUD in the U.S. beyond opioid treatment programs.

“Our analysis supports the Modernizing Opioid Treatment Access Act,” said Yu-Chia (Sam) Hsu. “This would allow patients to receive methadone for opioid use disorder in more outpatient settings and have it dispensed at pharmacies—similar to the practice already used for buprenorphine and common in many other countries.”

“These medications allow people to focus on rebuilding their lives: finding housing, reconnecting with family, working, and managing other health conditions,” added Thakrar. “In other words, these medications are not just symptom relief, but they are cornerstones to recovery. They are saving lives.”

The research letter, “Trends in Methadone Use for Pain and Opioid Use Disorder Among Medicaid Enrollees,” was published on November 21, 2025 in JAMA Health Forum. Authors included Yu-Chia (Sam) Hsu, Ashish Thakrar, Charles E. Leonard, Margaret Lowenstein, Colleen M. Brensinger, Warren B. Bilker, Kacie F. Bogar, and Sean Hennessy.

LDI Fellows Used Medicaid Data to Identify Individuals at Highest Risk for Cocaine- and Methamphetamine-Related Overdoses, Paving the Way for Targeted Prevention

Penn and Four Other Partners Focus on the Health Economics of Substance Use Disorder

Penn Medicine’s New Summer Intern Program Immersed Teens in Street Outreach Techniques

LDI Experts Offer 10 Solutions to Get More Help to Seniors With Addiction

More Flexible Methadone Take-Home Policy Improved Patient Autonomy

Research Brief: LDI Fellow Recommends Ways to Increase Availability