10 Noteworthy Research Articles from LDI in 2025

From AI-Powered Public Health Messaging to Stark Divides in Child Wellness and Medicaid Access, LDI Experts Highlight Urgent Problems and Compelling Solutions

Blog Post

In 2025, LDI Fellows shaped public dialogue and policy at the local, state, and federal levels. Our Fellows published more than 40 op-eds. They also informed policy decision-making by providing expert testimony and providing policy analyses to legislative offices to analyze the potential impact of proposed laws and regulations. Through these activities our Fellows led national conversations addressing issues ranging from Medicaid cuts and financing of rural health care to labor standards and long-term care.

Here are ten examples of LDI Fellows voices bringing evidence to shape policymaking:

Why Nursing Homes Should Provide More Nurses and Aides to Residents (February 2025)

Norma Coe and Rachel M. Werner defended the importance of minimum staffing levels in nursing homes in an op-ed in the New York Times.

Gene Hackman’s Death Shows Why Caregivers Need More Care (April 2025)

Shana D. Stites and Rebecca T. Brown cited the death of actor Gene Hackman to highlight the need to care for caregivers in an op-ed for the Chicago Tribune.

Two Looming Crises Threaten to Collapse U.S. Long-Term Care (May 2025)

Rachel M. Werner and a colleague described two existential threats facing long-term care for Stat News.

Experts: Medicaid Cuts Could Prove Fatal for Thousands (July 2025)

Eric T. Roberts and a colleague calculated the number of people who would die from the looming Medicaid cuts for MSNBC.com.

These Patients Have Nothing Else. Should That Be Enough for FDA Drug Approval? (October 2025)

Holly Fernandez-Lynch and a colleague criticized the FDA’s shortsighted decision to loosen standards for drugs treating rare diseases wrote in an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times.

Testimony: Restricting Youth Access to Nicotine and Tobacco Products (March 2025)

Andy Tan testified before the Philadelphia City Council Committees on Public Safety and Public Health and Human Services in support of Bill 250213 which proposed penalties for retailers who sell electronic smoking devices to minors. Dr. Tan’s testimony highlighted research on youth access to tobacco and nicotine and provided evidence to support passage of the bill. You can watch Dr. Tan’s testimony here.

Current status: Bill became law on September 11, 2025.

Letter: Projected Mortality Impacts of the Budget Reconciliation Bill (June 2025)

Rachel M. Werner, Norma Coe, and Eric T. Roberts collaborated with researchers at the Yale School of Public Health to estimate the potential mortality impacts of HR 1 (also known as the One Big Beautiful Bill). The researchers projected that retractions from HR 1 and the failure to extend Enhanced ACA Premium Tax Credits will result in over 51,000 preventable deaths.

Current status: HR 1 passed on July 4, 2025, and the enhanced ACA credits expired on December 31, 2025.

Comment: Impact of Proposed Changes to the Application of the Fair Labor Standards Act to Domestic Service on the Home Care Workforce (September 2025)

Rachel M. Werner and a colleague submitted a comment to the U.S. Department of Labor in response to the proposed rule entitled Application of the Fair Labor Standards Act to Domestic Service, that would roll back worker protections for home care workers. The comment highlights their research showing that the growing need for home care is outpacing the labor supply and points to evidence on the relationship between minimum wages and employment in the home care workforce.

Current status: Proposed rule is pending.

Testimony: Health Benefits of Philadelphia’s Sweetened Beverage Tax (October 2025)

Christina Roberto testified before the Philadelphia City Council’s Committee on Labor and Civil Service on Philadelphia’s sugar sweetened beverage tax. The hearing considered the tax’s future, examining its sustainability and potential changes. Dr. Roberto’s testimony highlighted the positive health impacts of Philadelphia’s tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. You can watch Dr. Roberto’s testimony here.

Current status: Sweetened Beverage Tax remains in effect.

Memo: Analysis of the Rural Health Transformation Program (December 2025)

Paula Chatterjee, Rachel M. Werner, and analyst Eliza Macneal completed an analysis of the Rural Health Transformation Program (RHTP) in response to a request from Ranking Member Ron Wyden of the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance to evaluate which states stand to benefit from the RHTP and how it does or does not invest in rural communities. The analysis found that estimated RHTP funding, based on an estimate of 75% of the funds that can be projected, is not clearly aligned with rural health needs.

Current status: CMS announced awards at the end of 2025.

Also see top LDI research articles of the past year.

From AI-Powered Public Health Messaging to Stark Divides in Child Wellness and Medicaid Access, LDI Experts Highlight Urgent Problems and Compelling Solutions

Administrative Hurdles, Not Just Income Rules, Shape Who Gets Food Assistance, LDI Fellows Show—Underscoring Policy’s Power to Affect Food Insecurity

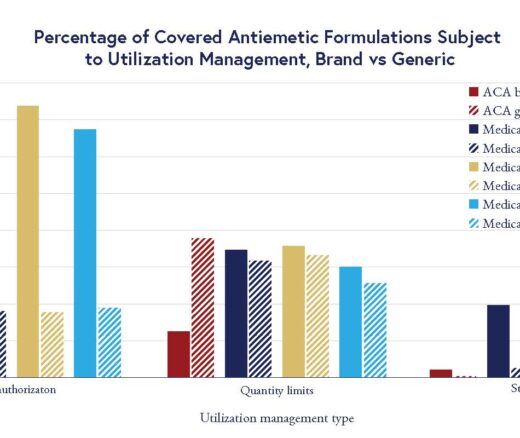

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior

The Evidence Suggests a Ban on Ads May Not Be A Well-Targeted Solution

Study of Six Large Language Models Found Big Differences in Responses to Clinical Scenarios