One Agency’s Maps Are Known For Documenting Redlining

But Many Other Factors Played a Role in Denying Loans, LDI Fellow Says

Population Health

Blog Post

Using a patient decision aid before a primary care visit can increase lung cancer screening of Veterans, according to a new randomized controlled trial. For nearly 10 years, national guidelines have recommended lung cancer screening for older people with a smoking history who are healthy enough for treatment if cancer is detected. However, in some U.S. regions, screening among eligible Veterans is lower than 1%.

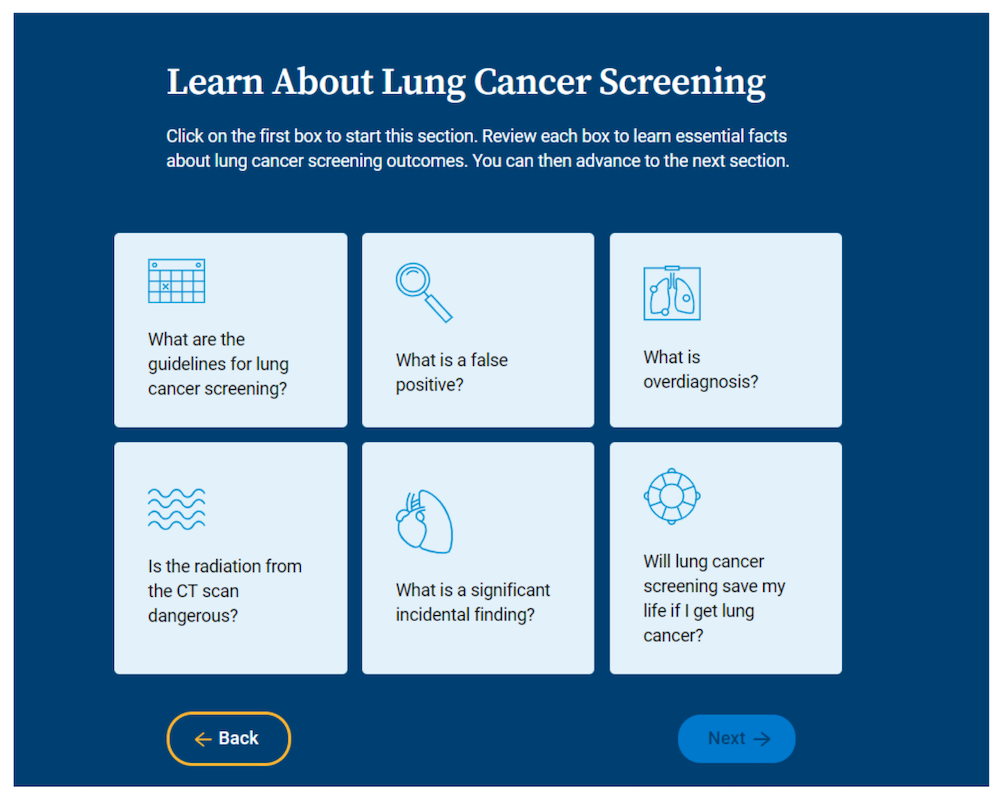

LDI Senior Fellows Marilyn M. Schapira and Sumedha Chhatre and colleagues led clinicians and Veterans in user-centered design of a web-based decision aid to help Veterans determine if lung cancer screening is a good choice for them.

Decision aids describe a procedure that can have both meaningful benefits and harms, and guide patients in thinking about their related preferences and values. These tools do not recommend procedures but support clinicians and patients in shared decision-making toward an informed health care choice.

The work with Veterans is part of Schapira’s growing research on decision aids for preference-sensitive health care choices such as management of early pregnancy loss with LDI Senior Fellows Courtney Schreiber and Sarita Sonalkar; breast cancer screening with LDI Senior Fellow Mitchell Schnall; and opioid pain treatment with LDI Senior Fellows Zachary Meisel, Jeanmarie Perrone, and Carolyn Cannuscio.

Shared decision-making with informed patients helps insurers and health care systems provide guideline-based care. This is especially important for preventive services such as lung cancer screening of people who are generally healthy. Payers and providers want to avoid harms to this population, which can range from transportation costs and missed work to overdiagnosis—detecting slow-growing cancer that would never be found or cause harm without screening.

Deciding about lung cancer screening is particularly complex for Veterans. Overall, they have high rates of smoking and environmental toxin exposure, but also conditions that can amplify screening harms such as anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

The annual procedure involves radiation exposure, although less than standard imaging by the same method. The images can reveal abnormalities outside the lung, such as in the thyroid, leading to more tests and treatment. Making an informed decision about screening requires considering these factors in the context of individual preferences.

Schapira and colleagues showed that Veterans who used the decision aid had higher knowledge about lung cancer screening benefits and harms than a control group. Knowing the potential harms did not increase anxiety and more decision aid users chose screening.

Schapira’s trial in VA medical centers in three states included 140 Veterans. About half used the interactive decision aid and half used a web-based general cancer prevention and screening program. In addition to meeting screening requirements, all participants had a primary care visit within 24 hours at which they could discuss and schedule a screening, if desired.

The decision aid uses pictographs to illustrate the benefits and harms of screening: For instance, for every 1,000 people screened, 21 are diagnosed with lung cancer. Of these, three lung cancer deaths are prevented but 18 will die of lung cancer. Also, three people have a major complication from following up false-positive results. The decision tool elicits values such as importance to the user of decreasing lung cancer mortality or avoiding radiation exposure. For the Veteran population, the decision aid also discusses and provides resources for mental health and quitting smoking.

Participants who used the decision aid scored higher on a survey about lung cancer screening knowledge than those in the control group. Knowledge stayed higher at three months. Participants’ decisional conflict—feeling informed and ready to make a decision about lung cancer screening—was the same for the groups at one and three months. At nine months, 45% of decision aid users were screened versus 25% of participants who received general cancer prevention information only.

“People who used the decision aid were more knowledgeable about the benefits and harms of lung cancer screening and more likely to undergo lung cancer screening,” Schapira said. “Importantly, using the decision aid did not increase anxiety or lung cancer worry.”

With both potential benefits and harms, decisions about lung cancer screening must match individual health goals and personal preferences. Schapira’s study showed that spending about 13 minutes with a web-based decision aid before a primary care appointment helped patients make an informed decision and obtain lung cancer screening without increasing general anxiety or lung cancer worry.

Schapira and colleagues are now planning for a real-world, pragmatic trial of the decision aid.

The study “Lung Cancer Screening Decision Aid Designed for a Primary Care Setting: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” was published on August 30, 2023 in JAMA Network Open. Authors include Marilyn M. Schapira, Rebecca A. Hubbard, Jeff Whittle, Anil Vachani, Dana Kaminstein, Sumedha Chhatre, Keri L. Rodriguez, Lori A. Bastian, Jeffrey D. Kravetz, Onur Asan, Jason M. Prigge, Jessica Meline, Susan Schrand, Jennifer V. Ibarra, Deborah A. Dye, Julie B. Rieder, Jemimah O. Frempong, and Liana Fraenkel.

But Many Other Factors Played a Role in Denying Loans, LDI Fellow Says

Offit and Buttenheim Criticize HHS Placebo Trial Mandate as Unethical, Misleading, and a Threat to Vaccine Confidence

A Penn LDI Virtual Seminar Explores the Latest Trends in Anchor Institution Operations

Neighborhood Perceptions May Also Affect PTSD and Depression Recovery After Serious Injury

A Penn LDI and Opportunity for Health Lab Virtual Seminar Explores Economic Assistance Programs

Testimony: Delivered to Philadelphia City Council