When Medicare Sent Patients Home Sooner, Mary Naylor Built the Safety Net

Her Transitional Care Model Shows How Nurse-Led Care Can Keep Older Adults Out of the Hospital and Change Care Worldwide

Improving Care for Older Adults

Blog Post

Produced in conjunction with the Population Aging Research Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

We generally assume that when a loved one moves to an assisted living facility or a nursing home, their needs for care are met by paid staff, relieving the burden on family and friends. Our new study in Health Affairs challenges that assumption, finding that family and friends continue to provide substantial amounts of care in these facilities, amounting to an invisible workforce, providing more than an extra “shift” of care every week in nursing homes and two “shifts” in assisted living facilities, on average.

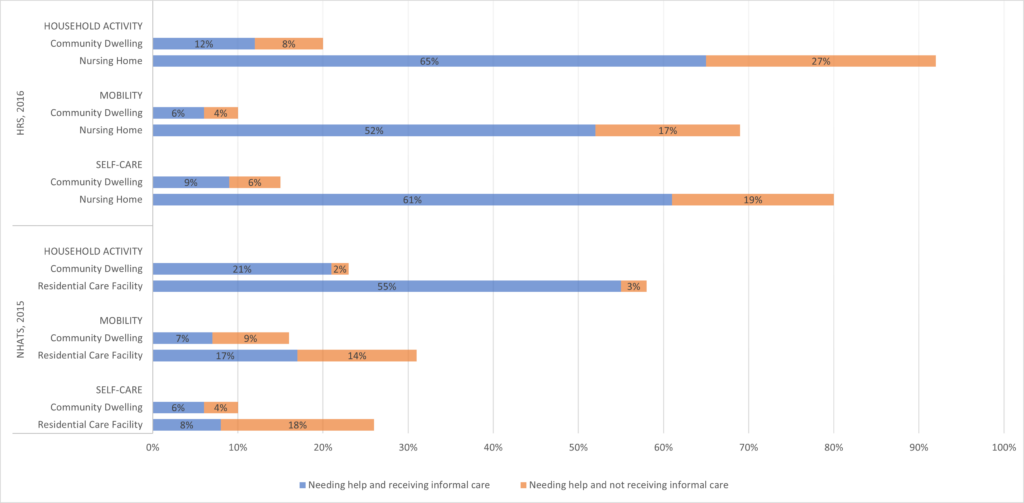

It has long been known that family and friends, sometimes referred to as informal caregivers, are the backbone of long-term care in the U.S. among community-dwelling individuals with functional limitations. However, this caregiving does not stop at the front door of residential care facilities. Not surprisingly, individuals living in these locations are more likely to need care than their community-dwelling counterparts. What is perhaps surprising is the extent to which unpaid family and friends are still helping to address those needs, despite the assumption that facilities have staff paid to do just that. Across a variety of types of care needs – household activities, mobility needs, and self-care – a higher percentage of individuals in residential care communities and nursing homes are getting assistance with these needs by informal care providers compared to their community-dwelling counterparts.

In this descriptive study, we used data from two nationally representative surveys from 2015 and 2016. A large portion of older adults received help with activities of daily living from informal caregivers regardless of residential setting. For example, as shown in Figure 1, 65% of nursing home residents received help with household activities as did 55% of assisted living residents. And the number of hours of informal care was substantial – up to 161 hours per month in community dwellings, 65 hours per month in assisted living, and 37 hours per month in a nursing home.

We can’t tell if this informal care is provided based on preferences of the elder and family members or due to needs of the residents being too great for the staff to meet alone. If it is the latter, it raises concerns about adequacy of staffing levels in nursing homes. It also raises questions about how needs are met among people who don’t have informal caregivers. Are their needs going unmet, or do staff spend more time with these residents, creating an implicit cross-subsidization between residents with and without family helpers?

Our findings help to explain the stories of staffing shortages and burnout in nursing homes under COVID despite no apparent drop in staff hours, when visitor bans were one of the first policy responses to the outbreak. The bans essentially eliminated this invisible workforce, increasing the care demands on the staff, on top of the extra work of the COVID protocols and infections themselves.

As we face yet another wave of COVID-19, and the faltering of the Build Back Better framework’s planned investment in caregivers, it is time to reconsider our long-term care policies. Family and friends provide considerable amounts of care in the community, after hospital discharge, and in residential facilities, with little support from, integration into, or even acknowledgement by our more formal systems of care. Making this invisible workforce visible is the first step, and supporting the families through payment and formal training could help both generations involved.

The study, Informal Caregivers Provide Considerable Front-Line Support In Residential Care Facilities And Nursing Homes, was published in the January 2022 issue of Health Affairs. Authors include Norma B. Coe and Rachel M. Werner.

Her Transitional Care Model Shows How Nurse-Led Care Can Keep Older Adults Out of the Hospital and Change Care Worldwide

Direct-to-Consumer Alzheimer’s Tests Risk False Positives, Privacy Breaches, and Discrimination, LDI Fellow Warns, While Lacking Strong Accuracy and Much More

New Therapies Inspire Hope, Even as Access and Treatment Risks Continue to Challenge Patients and Providers

Penn LDI Senior Fellow Yong Chen Is an MPI in the 10-Institution NIA Undertaking

Precision Diagnostics Give Patients Clearer Answers About What Drives Cognitive Impairment

Findings Suggest That Improving Post-Acute Care Means Looking Beyond Caseloads to Nursing Home Quality