Medicare’s Hidden Fix for High Drug Costs

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Blog Post

Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are foundational sources of coverage for low-income children in the United States, with about 40% of U.S. children enrolled. One key strategy to stabilize this coverage has been 12-month continuous eligibility, which ensures children can maintain insurance for a full year, regardless of temporary changes in income or family circumstances.

During the COVID-19 public health emergency, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) of 2020 strengthened this approach by providing enhanced federal funding to states that maintained continuous enrollment in Medicaid. All states opted into this provision, which paused disenrollments from March 2020 through April 2023. The end of this pause marked the beginning of the “unwinding”—a nationwide return to regular Medicaid eligibility reviews. While intended to restore standard operations, the unwinding posed a significant risk of coverage loss, particularly for children.

To evaluate these effects, LDI Senior Fellow Aditi Vasan and colleagues analyzed monthly Medicaid and CHIP enrollment data from January 2021 through December 2023 across 49 states and Washington, D.C. The study focused on two state-level policy factors: whether states had adopted 12-month continuous eligibility for children before the pandemic and how they structured their CHIP programs—as (1) a part of their Medicaid program (“Medicaid expansion”), (2) as a separate CHIP program, or (3) combination CHIP (a hybrid model with elements of both).

The findings were clear: Children’s Medicaid and CHIP enrollment declined substantially during the unwinding, but the extent of those losses was lower in states with continuous eligibility before the pandemic. For example, states without 12-month continuous eligibility policies saw monthly decreases in children’s Medicaid or CHIP enrollment of 1.2 percentage points, or about 15,500 fewer children per state each month. In comparison, states with 12-month continuous eligibility only saw monthly decreases of 0.7 percentage points, or about 9,000 fewer children per state each month. They also found that more integrated program designs may be better equipped to protect coverage during administrative transitions.

These insights arrive at a critical policy juncture. Since January 2024, all states are federally required to provide 12-month continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid and CHIP under the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, but several states are also exploring multi-year continuous eligibility policies for young children, potentially offering even stronger protections against churn.

In the Q&A below, Dr. Vasan discusses the study’s motivation, key findings, and what state and federal leaders should consider to strengthen children’s health coverage in the future.

Vasan: We knew that the end of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act’s continuous enrollment provisions—commonly known as Medicaid “unwinding”—would result in children across the country losing access to health insurance, often for administrative or procedural reasons. We wanted to better understand how state-level policies related to Medicaid and CHIP administration might influence those patterns. In particular, we were interested in whether existing policy options like 12-month continuous eligibility might protect children from experiencing churn during this unstable time. We felt that Medicaid’s unwinding provided a unique opportunity to study state-level variations in coverage loss in real time and to highlight actionable policies that could buffer against coverage disruptions for children.

Vasan: One of our most important findings was that states with prior 12-month continuous eligibility policies for children saw smaller enrollment declines during Medicaid unwinding. These policies didn’t eliminate coverage loss but may have helped limit its magnitude. In a previous study, we found that states that newly implemented continuous eligibility for children during the pandemic saw greater Medicaid coverage gains than states with prior 12-month continuous eligibility policies. So our current findings might also reflect that these pandemic-era-expanding states had a greater increase in enrollment during the public health emergency and therefore had more participants to lose during unwinding. We also thought it was notable that states with Medicaid expansion CHIP saw smaller coverage declines than those with combination CHIP, suggesting that combination CHIP programs may be more administratively complex or more challenging for families to navigate during renewal periods.

Vasan: We used an interrupted time series approach, which allowed us to examine changes in Medicaid enrollment trends before versus during Medicaid unwinding. We compared these enrollment trends across states with different types of CHIP structures (separate CHIP, Medicaid expansion CHIP, and combination CHIP) and states with and without prior 12-month continuous eligibility policies.

One limitation of our analysis is that we used aggregate Medicaid enrollment data, which means we couldn’t track what happened to individual children over time or assess how the effects of continuous eligibility might have differed based on beneficiaries’ race, ethnicity, primary language, or household income. Also, although we controlled for several state-level policies related to Medicaid unwinding, it is possible that other unmeasured differences in states’ Medicaid unwinding procedures affected our results.

Vasan: Our findings support the value of 12-month continuous eligibility for children and highlight the importance of Medicaid and CHIP program design in preserving children’s insurance coverage during periods of transition. As states consider multi-year continuous eligibility policies for children or changes to their CHIP program structure, we hope our findings can inform their decisions. We believe that state-level policies aimed at streamlining the Medicaid and CHIP certification and recertification processes are critical for improving children’s continuity of coverage and preventing coverage loss.

Vasan: In our future work, we are interested in exploring (1) the effects of Medicaid continuous eligibility and coverage policies on children’s health and health care utilization, and (2) how these policies might differentially impact beneficiaries across demographic groups, for example, based on their race, ethnicity, primary language, and household income.

In addition, as several states are now implementing multi-year continuous eligibility policies for children, we hope to be able to study the short-term impacts of these policies on children’s coverage stability, health and developmental outcomes, and patterns of health care utilization.

The study, “Continuous Eligibility Policies And CHIP Structure Affected Children’s Coverage Loss During Medicaid Unwinding,” was published in Health Affairs on March 3, 2025. Authors include Erica Eliason, Daniel Nelson, and Aditi Vasan.

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

A 2024 Study Showing How Even Small Copays Reduce PrEP Use Fueled Media, Legal, and Advocacy Efforts As Courts Weighed a Case Threatening No-Cost Preventive Care for Millions

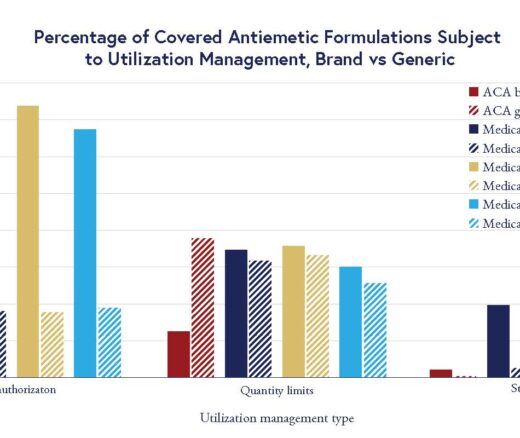

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use