Estimated Overdose Deaths Due to the Loss of MOUD in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

Research Memo: Delivered to House Speaker Mike Johnson and Majority Leader John Thune

Blog Post

On April 1, up to 14 million Americans started losing their Medicaid coverage—and many will end up with no health insurance at all, harming both their health and that of the health system. This “barreling toward a cliff,” as Kevin Mahoney, Chief Executive Officer of the University of Pennsylvania Health System, has put it, comes with the official end of the COVID-19 public health emergency. During the pandemic, the federal government paid state governments to keep patients on Medicaid rolls continuously, without making them periodically re-enroll as they normally would. Largely because of this continuity policy, Medicaid enrollment between February 2020 and October 2022 (Figure 1) soared by 20.2 million or almost 30%, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).

The unwinding of the pandemic regulations will change this trajectory. It means “the return of churn,” said Rachel M. Werner, Executive Director of the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, Penn’s hub for health policy research. Churn refers to people cycling on and off Medicaid, often because of state-imposed barriers to maintaining coverage and fluctuations in income common to people who work seasonal jobs or several part-time jobs.

Even after the Affordable Care Act (ACA) made changes to the re-enrollment process to reduce Medicaid churn, interruptions in insurance among Medicaid enrollees remained a problem. While states have cut Medicaid on their own in past years, this kind of reduction has never occurred in all 50 states at once.

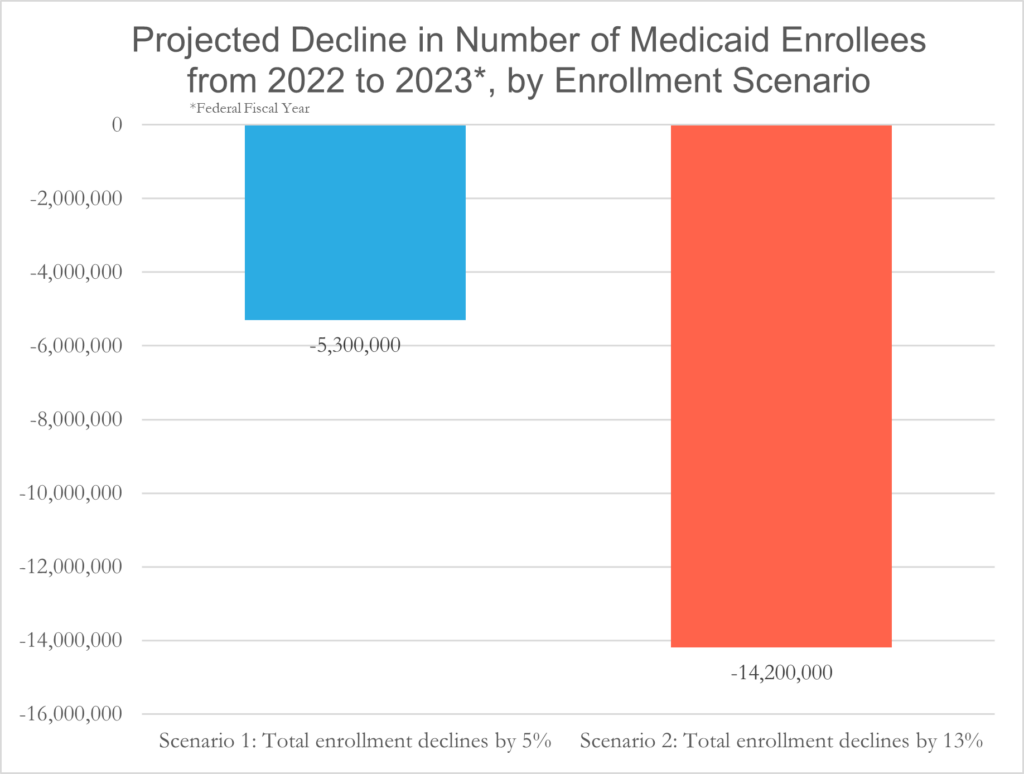

Using two different assumptions (Figure 2), KFF estimates that 5.3 to 14.2 million Medicaid recipients will lose coverage by next April 1. Close to half of people dropped off Medicaid rolls will be eligible to re-enroll, according to an estimate by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Others could become insured via the ACA, though they will face barriers to enrolling in insurance plans through the ACA Marketplace. “It’s a lot of steps to get either re-enrolled with Medicaid or enrolled in the ACA Marketplace,” said Mahoney, who is also an LDI Senior Fellow. Considering those difficulties, one calculation is that 3 million people, including 1 million children, will no longer have health insurance when the unwinding is completed. In Pennsylvania, where 43% of children under 21 years old are on Medicaid, 1 in 4 children is at risk of losing coverage, according to the Pennsylvania Partnerships for Children. “We’ve seen in the past few years that Medicaid can be a powerful tool to decrease uninsurance rates in this country. But we’re about to roll all that back,” said Werner.

| For more on this topic, see Primary Care Access for Philadelphia’s Medicaid Population by David Grande, MD, MPA and Addressing Structural Racism in Medicaid to Promote Health Equity |

Medicaid patients already have limited access to care, emphasized Paula Chatterjee, LDI Senior Fellow, LDI’s Director of Health Equity Research, and Assistant Professor of Medicine. Because the government program pays much less than private insurance, many providers in outpatient settings don’t accept Medicaid.

Losing insurance cuts care even more dramatically. “We know that in general the uninsured are more likely to present to the health care system with more advanced stages of illnesses such as cancer and chronic medical conditions. They are more likely to be hospitalized for conditions that could have benefited from outpatient care,” Chatterjee explained. People with disabilities, non-English speakers, and people of color will be disproportionately harmed.

The risks are especially serious for children, according to Aditi Vasan, LDI Associate Fellow and faculty member at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s PolicyLab. “Interrupting care can have negative health consequences for children, both in the short-term and the long-term. Kids who might be newly diagnosed with a condition like asthma or diabetes need immediate follow-up. They might not be able to get that follow-up, which could lead to worsening of these chronic conditions and ultimately lead them to be hospitalized and have long-term complications. Continuous coverage is important for all ages but it is especially important for children because they need preventive care like vaccines and they need quick follow-up for chronic conditions,” Vasan said. She added that the most at risk for losing coverage are those whose families speak languages other than English and the lowest income families, who are often juggling a lot of tasks, like working multiple jobs, and lack the time to go through difficult enrollment processes.

“Hospitals fall into the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ categories, and here, again, it’s the have-nots who are likely to be most burdened by the Medicaid unwinding,” said Mahoney. With an increase in uninsured patients, the amount of uncompensated debt in all hospitals will rise. “For rural hospitals and urban ones without a medical center, this is one more blow,” he said. “In and of itself, this lack of money isn’t going to close a hospital with marginal financials, but this could be the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

Mahoney is quick to point out that even hospitals with better financials like those within the Penn Medicine system are contending with a range of macroeconomic influences. U.S. hospitals in general are struggling financially. According to health care management consulting firm Kaufman Hall, about 50% of U.S. hospitals had operating losses in 2022 thanks to such factors as higher labor costs and the end of COVID-19 subsidies.

How will Medicaid recipients learn that they need to re-enroll or possibly find alternative insurance? “We need a massive communication effort,” said Mahoney. Legally, it is the states’ responsibility to inform enrollees about the unwinding. “The traditional ways of getting in touch with people—mail, landlines—are out the window. We’re pushing for the states to use modern communications, such as texts,” he said.

Patients who go to the hospital a lot—at least to the bigger ones—are likely to receive help from social workers in filling out applications, according to Mahoney. But those who rarely visit hospitals may be in for a shock when they want to see a physician after, say, discovering a lump in their breast, and discover they have no insurance coverage.

In many states, Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs), which account for almost three-quarters of Medicaid enrollees, have assumed some outreach duties and can help transition people from Medicaid to insurance purchased through an ACA Marketplace. “The MCOs have an incentive to keep people covered,” noted Vasan. In addition, said Chatterjee, “Out-patient practices across the country are doing everything they can to make patients aware that they can be disenrolled because of the unwinding and to help them get the support they need to allow redetermination.”

“States vary in the types of administrative burden they put in place for someone to be redetermined to be eligible for Medicaid. In some states it’s relatively simple. In other states, it’s paperwork upon paperwork, appointments and in-person visits—it’s quite a burden. If you are unable to meet these requirements, you are disenrolled,” Chatterjee said. Also, noted Vasan, “There’s a fear that states will not have the staff to handle large numbers of people trying to re-enroll.”

One way to streamline the process is what’s known as “ex-parte” renewals that verify eligibility based on available data sources, such as applications for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—formerly food stamps—or state wage databases, which reduce the burden on participants to fill out paperwork. Enrollment online or via phone also cuts down on barriers. With the federal nutrition program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), “some states allow people to enroll online. Just by virtue of that one small change, there’s a massive difference in enrollment between states that do and don’t allow that kind of application,” said Chatterjee. In the meantime, Medicaid has moved to guarantee continuity of coverage for children. As of January 2024, all states will be required to provide at least 12 months of continuous coverage for children under 19 years old. Starting in May 2023, one state, Oregon, will offer continuous coverage from birth until 6 years old. How else could access improve? “Ideally, all states would adopt the Medicaid expansion offered under the ACA and also increase Medicaid reimbursement rates to providers, which would increase Medicaid enrollment and also improve access to care for those on Medicaid,” said Werner.

Research Memo: Delivered to House Speaker Mike Johnson and Majority Leader John Thune

Research Memo: Delivered to House Speaker Mike Johnson and Majority Leader John Thune

Historic Coverage Loss Could Cause Over 51,000 People to Lose Their Lives Each Year, New Analysis Finds

Research Brief: New Incentive Structures and Metrics May Improve Program Performance

Research Memo: Response to Request for Technical Assistance

Immigration Crackdown and Medicaid Cuts Put Millions at Risk