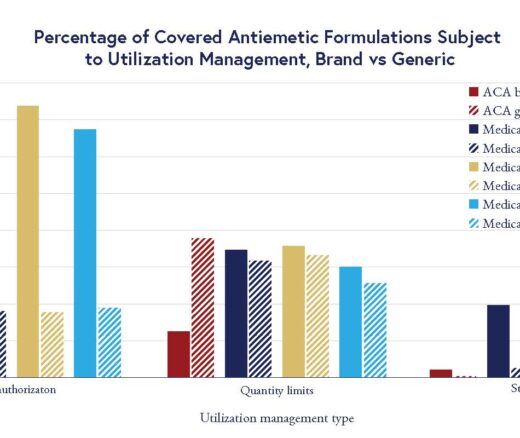

Insurers’ Utilization Management Tools Vary Widely on Anti-Nausea Drugs for Cancer

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Blog Post

What happens to people after they are stabilized and sent home from an emergency department (ED)?

Do they get the follow-up care they need to stay healthy and avoid returning to the hospital?

Such questions have long troubled Austin S. Kilaru, LDI Senior Fellow and Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine.

In a recent study, Kilaru found that recommended follow-up care is disturbingly rare for a large group of patients.

In general, he said, patients are expected to navigate their post-hospital care on their own. And that’s a nearly impossible task if no appointments are available, and if they lack symptoms or have little support.

In addition, the U.S. health care system has virtually no incentives to ensure that patients get outpatient care after an ED visit. Such care is not likely to happen if there’s no way to pay for it.

Kilaru and his team studied a group of chronically ill heart failure patients and were struck by the lack of timely follow-up care. The guidelines recommend that these patients see a doctor within seven days of discharge from the ED because they are highly likely to return to the hospital. But only a small fraction of them actually saw a provider, according to the study Kilaru and colleagues published last month in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

Kilaru discussed his work below in more depth.

Yes, we were surprised. When we send patients home from the ED, we recommend that many of them see their outpatient doctors within one week. This is particularly important for a condition like heart failure, where patients really need to be seen by their primary care physician or cardiologist. Patients would benefit from medication changes, repeat testing, and an in-person examination.

From prior work, we know that patients with heart failure are known to have a high risk of returning to the hospital, even if they were initially well enough to be sent home from the ED. While there have been great efforts to reduce hospital readmissions, relatively little attention is paid to patients who are discharged from the ED without getting hospitalized. That is a large number of people for heart failure, perhaps more than 250,000 people annually, but many millions when you consider other important disease conditions. Because this group of patients has not been the focus of policies or clinical pathways, we expected the outpatient follow-up rate to be low, but not this low.

One main takeaway is that this study almost represents a “best-case” scenario, as all patients in this study have commercial insurance. We do not know what the rate of follow-up would be for patients with Medicaid or traditional Medicare, but we could guess that it might be lower. Another takeaway is that we did observe some differences between patient groups, even though the rates were low for everyone. In particular, we noticed that women, Black patients, and those without recent outpatient clinic visits were less likely to attend an appointment within 30 days of the ED visit.

A final takeaway is somewhat hidden. It is important that the rate of return hospital admissions was high (nearly 20 percent), regardless of whether patients attended a follow-up visit or not. We have to start asking whether other approaches are needed to help patients after ED discharge, including telemedicine, home visits, and remote monitoring technology, rather than insisting that everyone see their doctor.

This study has a simple premise, but it was one that had not been explored. The question was straightforward: For patients who are discharged after an ED visit with a diagnosis of heart failure, how often do they see their doctor within one week or one month? Surprisingly, this question had not been answered among the general population.

One prior study based in the Kaiser system did find a much higher follow-up rate, but their integrated health system is unusual for its care coordination, access to care, and use of technology. There are also Canadian studies that have explored this topic and found a higher follow-up rate. Previous research within my specialty, emergency medicine, has often not used insurance claims data, but we had to use that type of data to capture care for tens of thousands of patients and delivered across multiple care settings, including the hospital, ED, and patient clinics.

The goal of my research portfolio is to generate evidence to make those recommendations! If I had a time machine to move forward a few years, I would have several recommendations at different levels. At the highest level of policy and payment, we need to start discussing the population of patients discharged from the ED as both a responsibility and an opportunity. In other words, we need payment models, quality metrics, and accreditation standards that create incentives to provide better care coordination services. These incentives may also seek to reduce some hospitalizations – for instance, when we admit patients to the hospital only because we are concerned that they will not be able to see their outpatient doctor in a timely way. Through improved post-ER care, we have an opportunity to improve quality, reduce cost (prevent return visits for worsening illness), and improve the patient experience.

At a more local level, we can also start to consider ways to identify high-risk patients leaving the ED and provide them access to expedited follow-up appointments, telemedicine follow-up appointments, or even more intensive services after discharge including home health. We should borrow from the considerable work that has been done to create pathways for patients discharged from the hospital.

One major question that we are trying to answer is whether an outpatient follow-up visit actually helps patients. It turns out that this question is deceptively challenging to answer, at least using insurance claims data. However, I suspect that even though helping patients see their outpatient physicians is objectively a good thing, one outpatient visit may not be enough to help the highest-risk individuals. These patients may need daily contact, close medication and symptom monitoring, and assistance with social needs.

Another question is whether these trends hold true for other disease conditions, and whether the use of telemedicine following the COVID-19 pandemic has changed anything.

Finally, a major goal of my research is to use improved care coordination and remote monitoring to actually reduce hospitalizations for stable patients – in other words, if we build a better follow-up system, could we actually send more patients home from the ED, again seeking to improve overall quality of care, reduce cost, and improve patient (and provider) experience?

The study, “Incidence of Timely Outpatient Follow-Up Care After Emergency Department Encounters for Acute Heart Failure” was published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes on September 8, 2022 by Austin S. Kilaru, Nicholas Illenberger, Zachary F. Meisel, Peter W. Groeneveld, Manqing Liu, Angira Mondal, Nandita Mitra, and Raina M. Merchant.

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Research Brief: Shorter Stays in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Less Home Health Didn’t Lead to Worse Outcomes, Pointing to Opportunities for Traditional Medicare

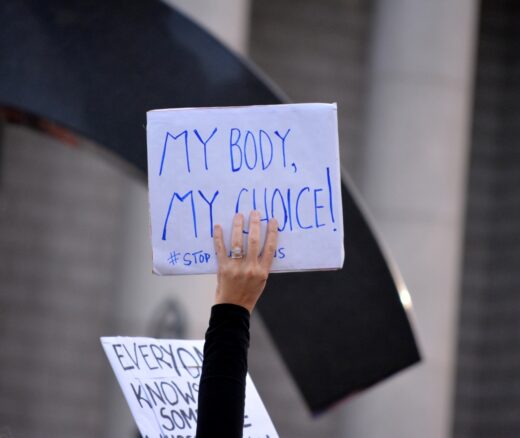

How Threatened Reproductive Rights Pushed More Pennsylvanians Toward Sterilization