Acupuncture Could Fix America’s Chronic Pain Crisis–So Why Can’t Patients Get It?

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

Blog Post

Integration has been a buzzword in health policy for decades. Researchers have touted integration as a central strategy for lowering cost and improving quality as health care becomes more specialized. However, we argue that so-called vertical integration—merging different aspects of health care into one larger organization—has failed to achieve these goals.

Along with other structural “solutions” for addressing the ills of fragmented health care, vertical integration may have actually made things worse. How so? As we (along with collaborator Stephen Shortell of the University of California, Berkeley) described in a recent article in Social Science and Medicine, health care organizations implementing vertical integration have emphasized combining health care structures (a front-office preoccupation) while ignoring the organizational processes that clinically integrate caregivers (a front-line preoccupation). They have also mistakenly assumed that combining structures—such as primary care and home health care or outpatient and inpatient care—naturally leads to clinical integration.

But to achieve meaningful integration in health care, providers need to communicate and collaborate beyond their immediate area of practice or specialty. There also needs to be interaction among caregivers and their work units. As such, health care organizations need a new approach if they want to succeed in achieving integrated care: they must leverage knowledge about how social networks operate across all levels of an organization and design care to improve relational processes within and across these networks.

We argue that all health care integration efforts should focus not on structures but rather on relational ties. It’s not so much counting connections in organizations that matters but what happens within those connections—including collaborative decision-making, goal sharing, information sharing, and mutual respect. These dynamic interactions and interpersonal networks support flows of information, influence, resources, actions, and support throughout all parts of health care systems. Unlike much of the research on structures of integration, research on such “relational coordination” (including here and here) suggests that it improves outcomes, quality of care, patient safety, patient engagement, provider experience, efficiency, and clinical integration.

As a result, the study and practice of integrated health care should begin to focus on the characteristics of the networks among the players in the health care ecosystem. Social network analysis provides a useful method to measure the strength of connections and what actually happens in these connections (e.g., sharing of goals and knowledge).

To illustrate this social network perspective on integration, consider some examples of the popular “care coordination” intervention, which has achieved mixed results:

Integration is widely seen as critical to achieving better outcomes in health care. However, the current narrow focus on structures misses the mark. We believe that to achieve better outcomes, health care organizations and the researchers that study them need to focus on maximizing the potential of the social networks that are the foundation of health care delivery.

The study, Integrating Network Theory into the Study of Integrated Healthcare, was published in the March 2022 issue of Social Science & Medicine. Authors include Lawton R. Burns, Ingrid M. Nembhard, and Stephen M. Shortell.

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities

Research Brief: Shorter Stays in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Less Home Health Didn’t Lead to Worse Outcomes, Pointing to Opportunities for Traditional Medicare

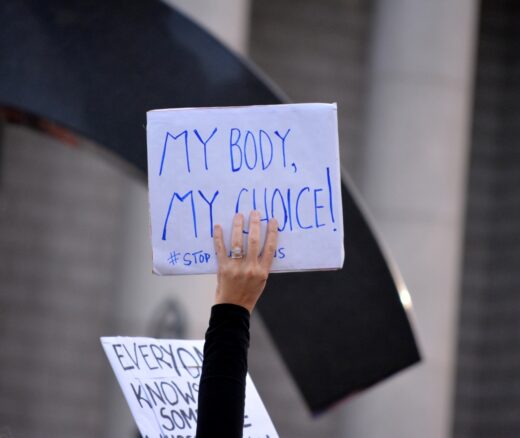

How Threatened Reproductive Rights Pushed More Pennsylvanians Toward Sterilization

Abortion Restrictions Can Backfire, Pushing Families to End Pregnancies

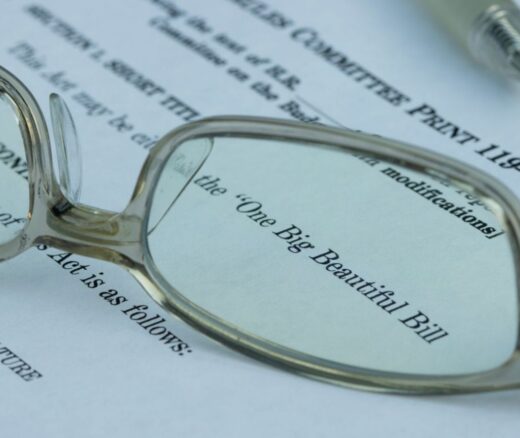

They Reduce Coverage, Not Costs, History Shows. Smarter Incentives Would Encourage the Private Sector