How Playing Games May Save People’s Lives

The Growing Use of Gamification in Health Motivates People to Exercise More and Take Other Actions to Improve Their Physical Well-Being

Health Care Access & Coverage | Improving Care for Older Adults

News | Video

As the idea of shifting delivery of acute hospital care into the home continues to gain traction, the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute (Penn LDI) invited a panel of four top experts in the field to discuss the benefits and challenges of such a dramatic policy and practice change. The event was titled “Health Care at Home: A New Frontier,” and co-sponsored by the Penn Center for Improving Care Delivery for the Aging (CICADA).

Clarifying the subject as she opened the session, moderator and LDI Executive Director Rachel M. Werner, MD, PhD, emphasized that it’s far broader than the softer kinds of “home care” now provided by home health agencies. It includes hospital acute care, post-acute care and primary care, along with 24/7 remote monitoring, daily provider visits, acute and chronic disease management, and other diagnostic services — all delivered in the patient’s home rather than a clinical facility.

“We’ve learned during the COVID-19 pandemic that a wide range of conditions can, and perhaps should be treated in the home,” said Werner. “So, there’s new energy around moving health care into the home, and there may be a window of opportunity to fundamentally change the way policymakers, providers and payers think about how, when and where patients are treated.”

The concept was hugely boosted in March of 2020 when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) launched the Acute Hospital Care at Home program to increase hospital capacity and expand overall treatment resources as COVID-19 infections and deaths spread across the country. Currently, 187 hospitals in 83 health systems in 34 states are authorized to provide in-home acute care services for the duration of the pandemic.

The impact of this home-based acute care CMS waiver program was further augmented by the explosive growth of telehealth via phone, video, and text, along with a similar expansion of the availability and use of remote biomonitoring systems attached to the patient or otherwise installed in the home.

Two questions that come out of all this are: What happens to acute care in the home after the pandemic and what are the prospects for taking such a disruptive model to national scale?

The four panelists weighing in on the issues were Meena Seshamani, MD, PhD, CMS Deputy Administrator and Director of its Center for Medicare; Bruce Leff, MD, Director of the Johns Hopkins University Center for Transformative Geriatric Research; Craig Samitt, MD, former President and CEO of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota; and Reed Tuckson, MD, FACP, former Executive Vice President and Chief of Medical Affairs at UnitedHealth Group.

In a fast-paced hour, the panelists declared the largest challenges to implementation to be the required changes in payment systems, workforce logistics, and embedded cultural resistance across all of health care. They also discussed the likely impact of such a new system on health equity and the current evidence base about the model’s safety and efficacy.

“It’s fair to say that Hospital at Home may be one of the most evidence-based health services delivery innovations of the last 30 or 40 years,” said Leff. “This includes scores of randomized controlled trials, a number of systematic reviews and meta analyses, as well as a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) demonstration study done at Mount Sinai in 2018.”

In the 1990s at Johns Hopkins, Leff developed and tested an acute-care-in-the-home model for frail, elderly patients. Trademarked by Hopkins as “Hospital at Home,” the model was first adopted in 2008 by Presbyterian Healthcare, a New Mexico health system with nine hospitals across that state.

Leff said the model is now being used in the U.K., France, and Australia, and a variety of rural and urban settings in the U.S. where “there is some early data to suggest it really addresses some equity issues.”

“You should think about this kind of program in two main flavors,” Leff continued. “Number one is substitution or admission avoidance — the patient goes from the emergency department directly home. The other flavor is of completing a hospitalization at home. The patient is quite sick and comes into the hospital, gets stabilized, and goes home to get the ongoing hospital-level care they need there.”

Former Minnesota Blue Cross head Samitt favored expanding the scope of the acute care-at-home vision to include a broader range of health-related services. “If our goal is to deliver more convenient, cost-effective and quality care in the optimal setting, wouldn’t we want to drive a complete reconfiguration of where and how we receive care?” he asked. “We should build an ecosystem that would deliver primary care, non-surgical specialty care, chronic disease management and even some ancillaries or testing via the home. It would also include a focus on wellness, prevention, avoidance and cure in the home. So, it’s not just about shifting the old hospital system into houses, but significantly reducing the need for hospitalization in the first place.”

Medicare executive Seshamani said her agency had a central role to play in any expansion of the current care at home programs. “We want to advance health equity, expand access to care, drive high-quality, person-centered care and promote affordability and sustainability,” she said.” The CMS Acute Hospital Care at Home waiver is one example of where we have allowed capable hospitals to treat certain patients with inpatient level care in their homes through this public health emergency.”

“Public-private partnerships are going to be very important for this work as we start thinking more holistically about building the capacity in communities to engage when you’re not using the infrastructure of a hospital anymore,” Seshamani continued. “You have an infrastructure of a home and the caregivers that are in that person’s environment addressing social needs, which oftentimes can be easier done when you are meeting people where they’re at. Looking forward, where are there opportunities to help connect the various sectors that play a role in care? So, think about the public health workforce, for example, and the role community health workers can play in providing this more holistic care. I think those are some examples of the opportunities.”

Tuckson similarly underscored the importance of rethinking workforce logistics in any post-pandemic expansion of at-home acute care. “This is an important augmentation to the paradigm of care delivery, and I’m excited about it. The challenge of course, is that people of color, and disadvantaged and marginalized communities, do not very often have the resource base at the community level that can migrate into the home to help dissipate some of the challenges of managing patients in this environment.”

“We do see the potential for great opportunities here as we start to identify new workforce training and needs,” Tuckson continued. “We’re going to need to use this as another spur to recruit people from underserved communities to be not only the primary care clinicians and nurse practitioners, but the care managers, social workers and in-home support systems that are needed.”

“I’m also very excited by the opportunity to get assessments of the capacity of a community and its individual homes,” said Tuckson. “This gets us into the home and uncovers social determinants of health issues, internet issues, and care support issues, then feeds that data back to the system to address them along with other things we’re trying to do for more holistic, patient-centered care.”

Werner asked what happens to the business model of brick-and-mortar health care systems if large numbers of their patients ultimately avoid the hospital to be treated at home?

Former Minnesota Blue Cross and Blue Shield CEO Samitt said, “As with a lot of things in health care, I think it’s about striking the right balance between the two. In figuring that out, we’re going to want to test the safety and efficacy of care at home for each major and minor condition. After we do that, I think we should request, or even require, a reduction in brick-and-mortar hospitals and clinics if we see a growing use of acute care at home.”

“If we don’t require a reduction, brick-and-mortar hospitals will still need sufficient revenues to maintain their existing physical plants,” continued Samitt, “That essentially will mean paying more per hospitalization within the traditional facilities equal to the total cost of hospitalization today. Plus, we will also then incur the cost of hospitalizations in the home. So, if we don’t address the transition from brick-and-mortar [hospitals] to home — of high asset to light asset — then I think a major intent of why we’re doing hospital in the home — to make health care more affordable — goes away, and it wouldn’t lead to any net savings in the health care system.”

As the session ended, Werner asked each participant to name the most important thing that needs to be done now to accelerate or maintain the current momentum of the shift towards acute home care. They responded:

Tuckson: “We don’t want to look at this in silos as we figure out the best setting of care. Focus on the array of community-based supports that allow families to do the best they can for their member, and then have others participate around them, depending on the nature of acuity and the intensity of need. We have to get to a place in America where we are focused on the robustness of those community-based assets.”

Samitt: “The shift will be accelerated by innovative disruption by startups in health care. There are already some very big organizations — including Fortune 500 companies — getting into the space with what they’re calling omnichannel care delivery models that are solutions developed for retail, home, and virtual. If we don’t want to be obsolete, we need to re-align the existing incumbents in payment reform and more aggressively accelerate to a value-based payment system.”

Seshamani: “We need to double down on the opportunities for partnership and alignment under more holistic models of care. It’s marrying the payment reforms with the transformation of care, because payment is just one side of the coin. It needs investment in these holistic models of care, home-based care being an important part of that, while also creating investment in the communities and supporting change in the way care is actually delivered there on the ground.”

Leff: “It’s hard to change hardwired behaviors of health systems. We need co-development of change in payment that can drive culture change and somehow make that culture change really sustainable and really sticky. I do think the startups can push on that. And, we must start bringing together the medical and the social and really invest in communities. All these health systems we’re talking about take Medicare payment and get community dollars, but they don’t always use them the way I think they’re intended to be used. So maybe we need some pushing on that as well.”

The Growing Use of Gamification in Health Motivates People to Exercise More and Take Other Actions to Improve Their Physical Well-Being

Pa.’s New Bipartisan Tax Credit is Designed to be Simple and Refundable – Reflecting Core Points From Penn LDI Researchers Who Briefed State Leaders

Focusing in on Some of Health Care Policy’s Most Urgent Issues

Highlighting 10 Ways LDI Fellows Put Their Research Into Action

From AI-Powered Public Health Messaging to Stark Divides in Child Wellness and Medicaid Access, LDI Experts Highlight Urgent Problems and Compelling Solutions

An LDI Expert Offers Three Recommendations That Address Core Criticisms of the ACA’s Model

Administrative Hurdles, Not Just Income Rules, Shape Who Gets Food Assistance, LDI Fellows Show—Underscoring Policy’s Power to Affect Food Insecurity

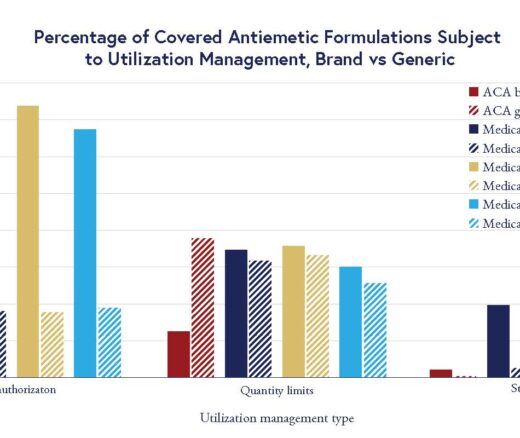

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

A Penn LDI Virtual Panel Looks Ahead at New Possibilities